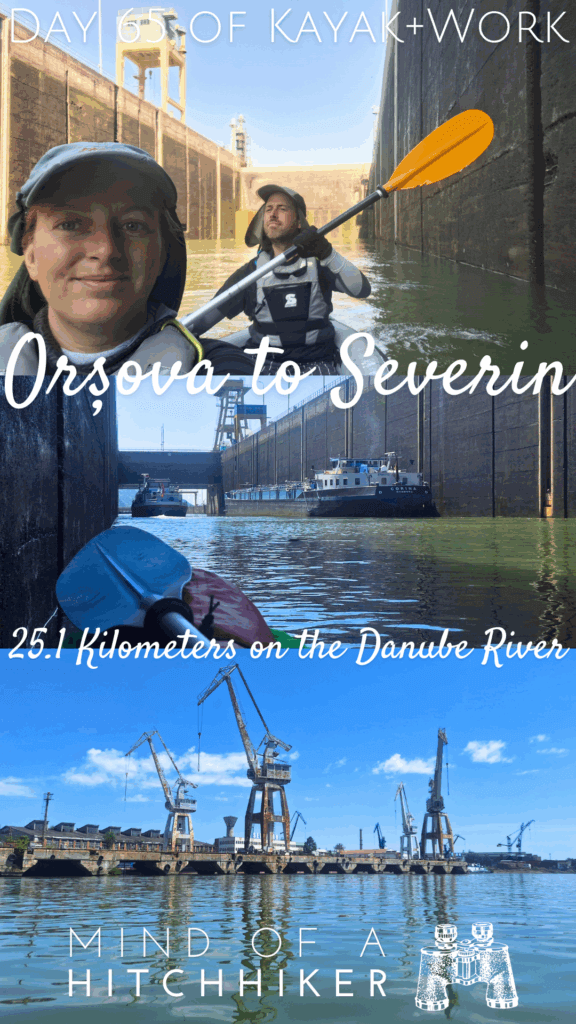

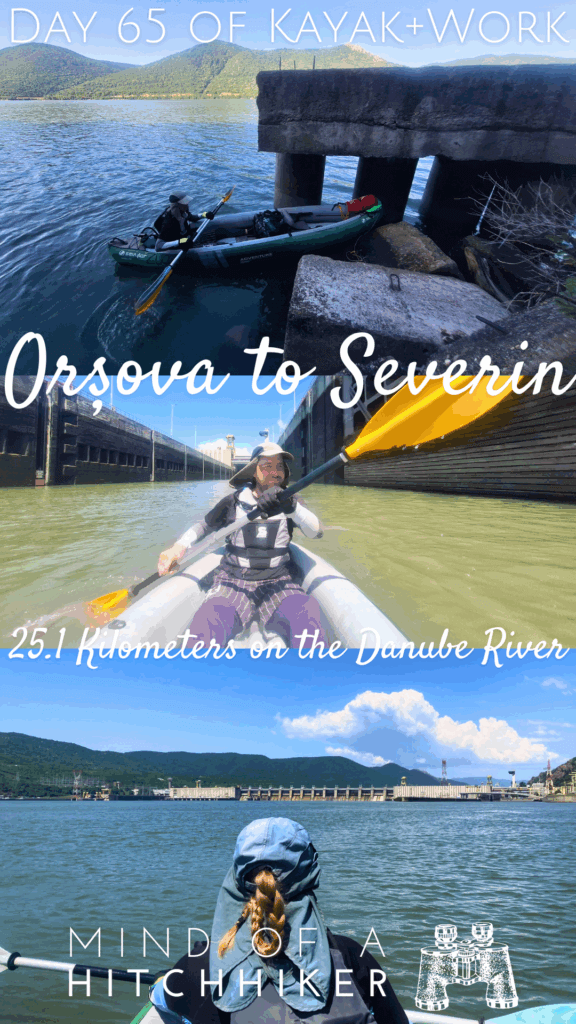

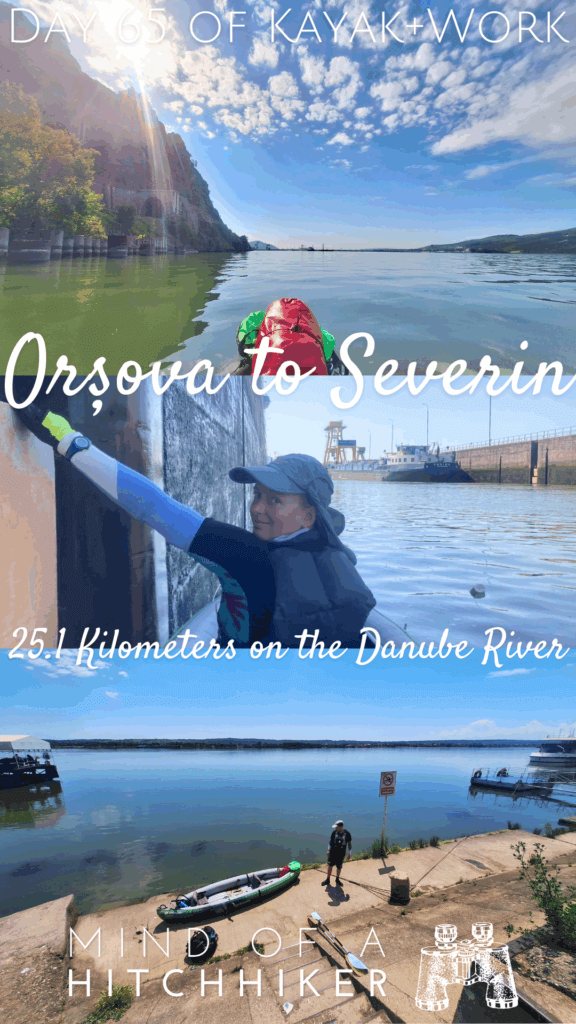

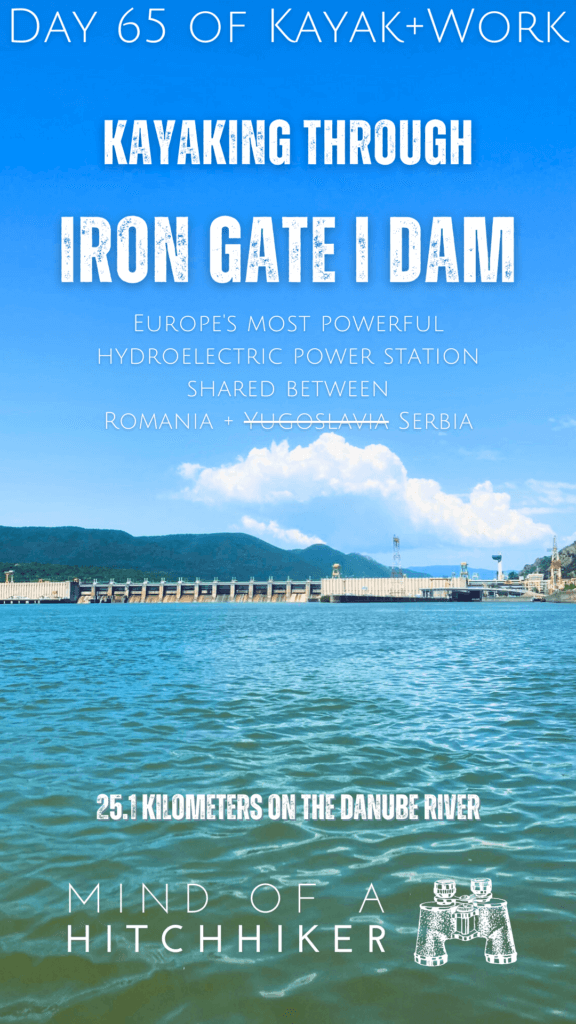

This kayak trip happened on Monday the 27th of May, 2024. We paddled from Orșova to Drobeta-Turnu Severin on the Romanian side of the Danube in the border area shared with Serbia. We also had to pass through the Iron Gates I dam (Romanian: Porțile de Fier I – Serbian: Đerdap I). Portaging is not feasible, so we had to go through the lock with the big ships!

Want to travel the (entire) Danube River in an adventurous way? Join our Facebook group Danube River Source to Sea: Kayak / Canoe / Bike / Hike / Sail to find your community

Contents

- 1 Kayaking Through Locks: Research + Stress

- 2 Paddling out of Orșova into the Sip Gorge

- 3 Remembering Ada Kaleh

- 4 Preparation for the Lock: Transponder On

- 5 The Luckiest Timing in History

- 6 Iron Gates I Lock: A Two-Stage Descent

- 7 Water Police in Drobeta-Turnu Severin

- 8 The Train from Drobeta-Turnu Severin back to Orșova

- 9 Five Days in Drobeta-Turnu Severin

- 10 Useful kayaking info? Consider buying me a beer!

- 11 Spread the word? That’s your good deed for today!

Kayaking Through Locks: Research + Stress

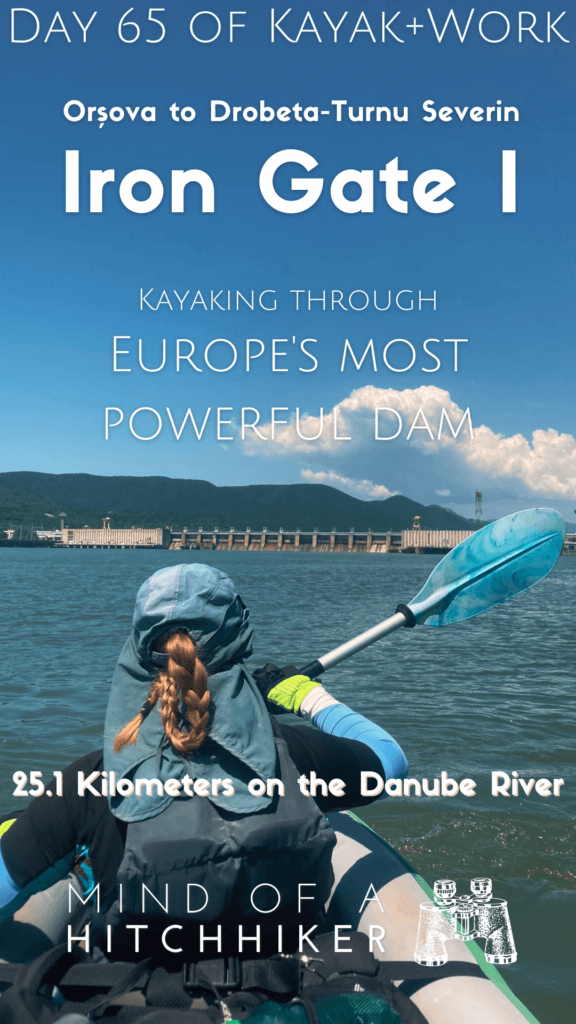

The Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station is the 53rd obstacle on the Danube for us since 2019, but it’s the first one in 2024. So far, we’ve kayaked more than 500 kilometers in 2024 without encountering a single dam. That’s (generally) a good thing! But now it’s time to face off with the biggest boss of them all.

The Iron Gate I dam is the biggest dam on the Danube and one of the biggest in Europe. The difference in water levels on both sides is about 35 meters, while the dam height itself is 60. At least, that’s how I interpreted the data. Though a 35 meter drop for ships passing through the locks is quite a lot, it’s not the highest rise/fall for a ship lock in Europe. That one belongs to the Carrapatelo Dam on the Douro River in Portugal, which is cited as a tall 57 meters, 45, or 35 depending on which bullshit source you use.

(Researching the tallest rise/fall locks in Europe or elsewhere was an absolute pain in the ass. At least there seems to be consensus that Oskemen Lock on the Irtysh River in Qazaqstan has the biggest rise/fall at 45 meters)

Perhaps the reason the Iron Gate I doesn’t appear on shortlists about big locks is that it’s a two-stage lock, with the descent split up in two journeys.

Paddling out of Orșova into the Sip Gorge

I’d set an alarm for six. When I got up, there was still time to witness the sunrise over the hills across the Orșova Valley (Romanian: Valea Orșova). We had coffee, packed, applied sunscreen. The whole ritual for a day of kayaking the Danube. One cargo pushtow hung out at several anchored barges with its lights on. Perhaps they’re leaving today, in direction downstream?

We walked downstairs and crossed the street to the launch spot a little after seven. Pumping up Zucchini and packing her up with our reduced amount of luggage was a breeze. When we got to the launch spot, we saw that the water levels had risen since we arrived in Orșova. Still, the amount of space we had to launch was good enough. We kayaked away from Orșova across the drowned valley at 7:31. No dogs following us, just us with the peaceful waters reflecting the morning sun.

There was quite some shipping activity this morning. A fast cruise ship sailing downstream, something going up, and several empty cargo ships going down towards the locks. I couldn’t wait to be at the lock area standing by for a companion ship of any kind. I basically didn’t stop paddling until we had crossed the Orșova Valley and entered the last 10 kilometers of river before the dam. But the pushtow we could see from our apartment wasn’t going anywhere. At least not right now.

Once we were at the forested edge at the end of the Orșova Valley and the last gorge of the Iron Gate canyon – the Sip Gorge – we heard a lot of birdsong and startled a few Pygmy Cormorants. It took us half an hour to cross the bay, which was about 2.6 kilometers. Not a great speed, but also not terrible.

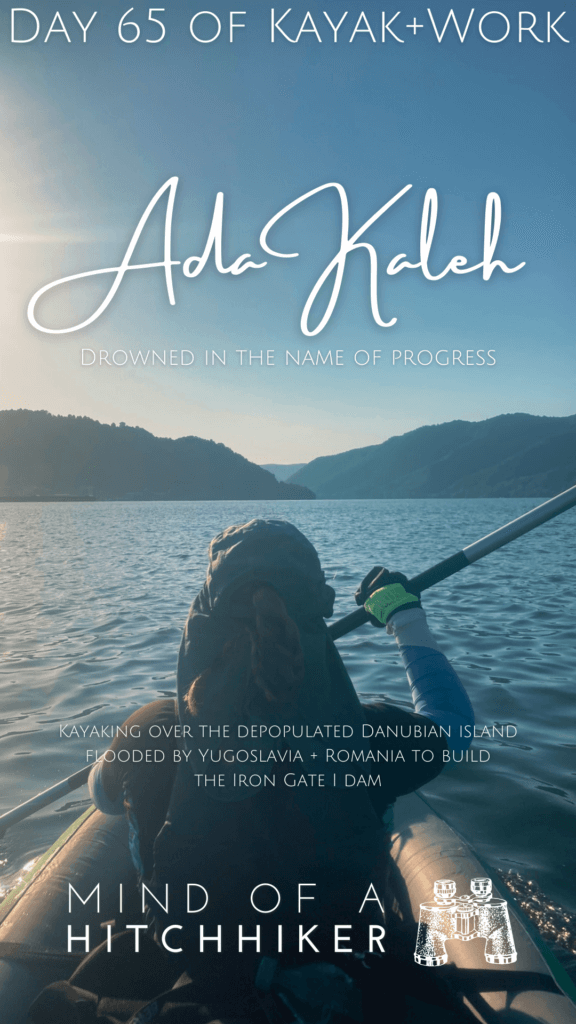

Remembering Ada Kaleh

For more info about Ada Kaleh and wonderful old pictures, check out Danube Islands blog.

Once in the main Danube, our speed increased. Is this… current? Let’s not get too excited.

Jonas wanted to shortcut the right turn a bit, so we aimed for a mountain peak on the Romanian side of the river much further downstream. In this way, our route took us right over the former river island of Ada Kaleh, which disappeared beneath the Danube waters in 1972. Yugoslavia’s Tito and Romania’s Ceaușescu opened the dam in May of that year.

The 600 – 1000 mostly Turkish people that lived on Ada Kaleh were told to leave the island in 1967 in anticipation of its submersion. As the island was under Romanian jurisdiction after World War I, most people migrated to the Romanian region of Dobruja (city of Constanța) or to Turkey at the invitation of the Turkish government.

The island had a thriving economy over many centuries. As it lies in the lower parts of the Iron Gate canyon, whoever controlled Ada Kaleh controlled the river here. It had a fortress, mosque, bazaar, cafes, vineyards, gardens, and houses. During the 20th century, Ada Kaleh was also an early duty-free stopover for tourists, selling local tax-exempt products such as sweets and tobacco. Not much has changed, in that regard.

After its depopulation, local structures were knocked down, with the intent to rebuild them downstream below the dam on the Romanian Șimian island. They rebuilt the fortress on that island under the nomer “New Ada Kaleh”, but since, the project has remained incomplete and things have fallen into disrepair.

I remember first reading about Ada Kaleh more than a decade ago. I also vaguely remember about how parts of the structures on the island – such as the minaret – reveal themselves during times of drought. But as I research this today, I can’t find such sources and it’s hard to believe the water levels can go so far down (some 33 meters) to reveal the flat river island. Perhaps I’m mistaken and confused Ada Kaleh with the partially-submerged church in Catalunya or any number of places where people had to vacate their properties to make way for reservoirs.

Was it worth it, losing the unique cultural enclave of Ada Kaleh for hydropower? Are the sins of the grotesque engineering projects of the 60s and 70s in the name of progress worth it? Ada Kaleh isn’t the only thing affected by the dam, but its the most prominent example because it also affected a minority. Here are the pros and cons of the Iron Gate I dam, that I can think of.

The pros:

- Improved river navigation for cargo and cruise ships

- Electricity for about 20% of Serbia’s (at the time Yugoslavia’s) population and industry and electricity for less than 7% of Romania’s population and industry

- Permanent border crossing between Serbia and Romania?

- Better water level regulation? Flood prevention? (Not according to our host in Golubac, who lives quite up the hill and his house was flooded in 2015)

- Employment at the locks??

The cons:

- People displaced

- Towns and railroads had to be moved

- Countless archaeological sites lost to the water

- No strong currents for kayakers, no suitable place to portage the dam

- Riparian zone forever changed, making the gap to cross too big for some species, attracting species that love a lack of current

- Ugly dam

- Sediment travel largely stopped

- Water quality goes down

- Serbia hiring russian help for its turbine modernization in the 2000s

- Fish migration stopped because they forgot to build the fucking fish ladder

There’s absolutely no talk about dam-removal for Iron Gate I or II. In fact, Serbia is thinking of building Đerdap III near the village of Dobra. It’s a different type of hydropower plant, more like a battery, like we’ve seen on the Danube before in Austria.

Preparation for the Lock: Transponder On

After one hour of paddling, we were in the middle of the turn near the Romanian village of Ilovița. We were paddling closer to the Serbian side below Đevrin Mountain than the Romanian shores, so I thought it was time to straighten out our course and aim to get closer to the left bank of the Danube again.

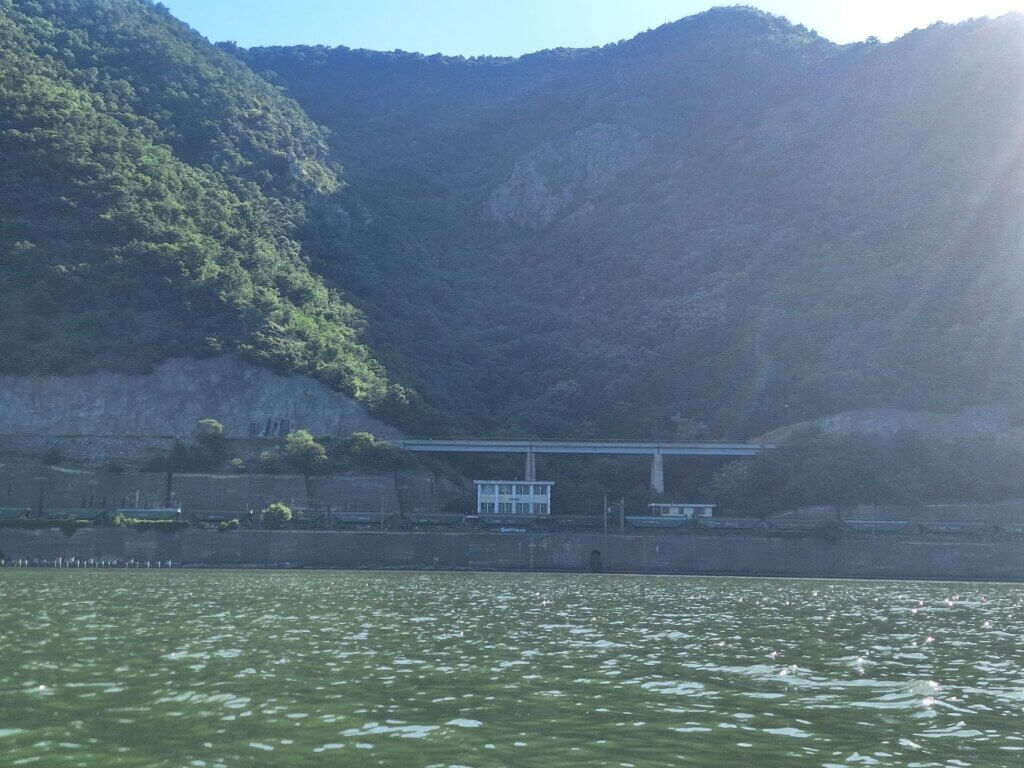

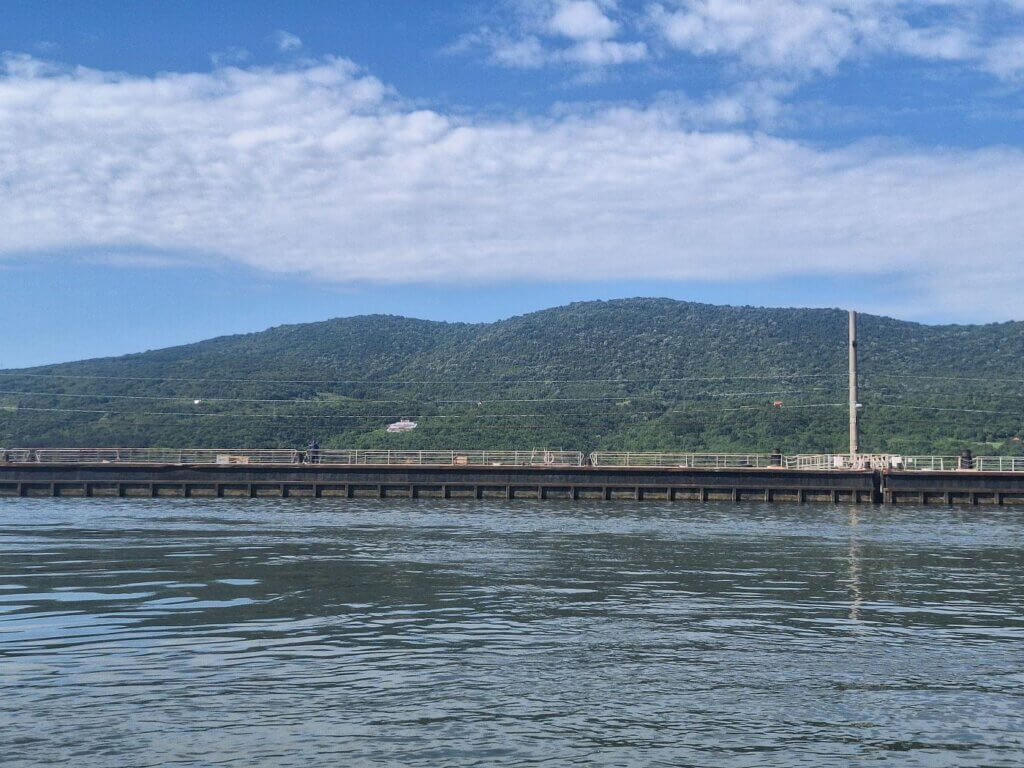

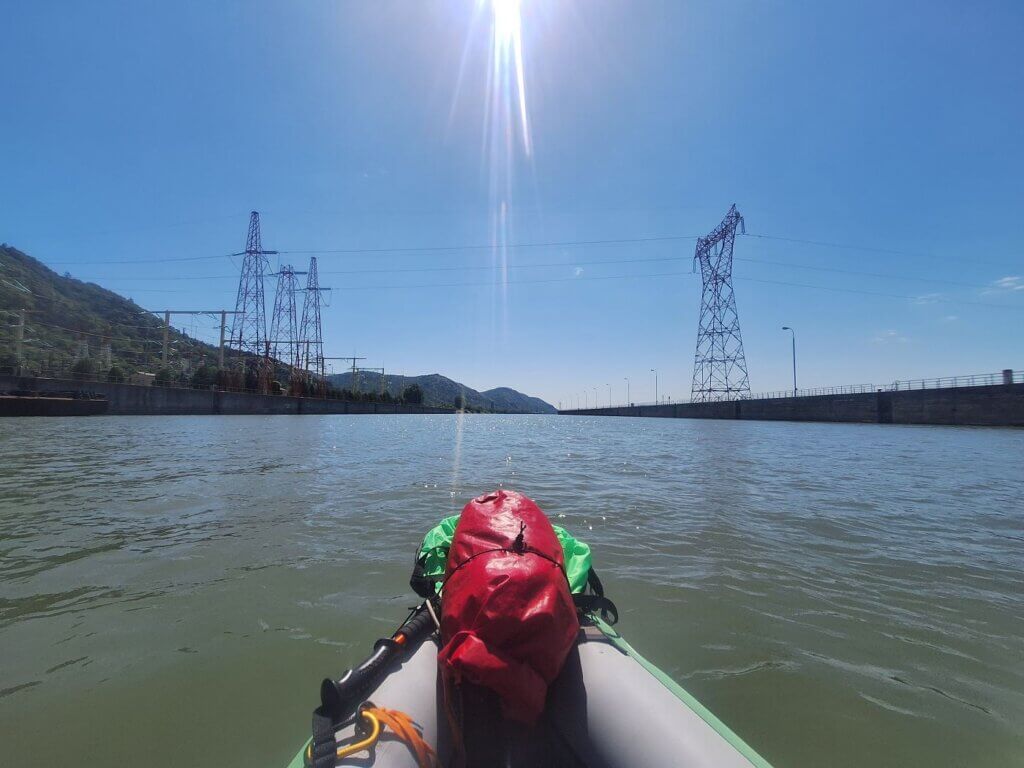

As the left and right slopes of the Sip Gorge untangled themselves from each other and a gap between them appeared, we saw the hazy indications of the Iron Gate I dam in the distance. At first, we mostly saw its towers and cranes. Then, as the gap widened, the concrete ledge of the dam itself. Beyond it, only sky.

The sluice gates were still almost 10 kilometers away. We wouldn’t be there anytime soon. We were scanning the horizon for ships coming upstream, and ships coming from behind going downstream. But we were alone on the Danube.

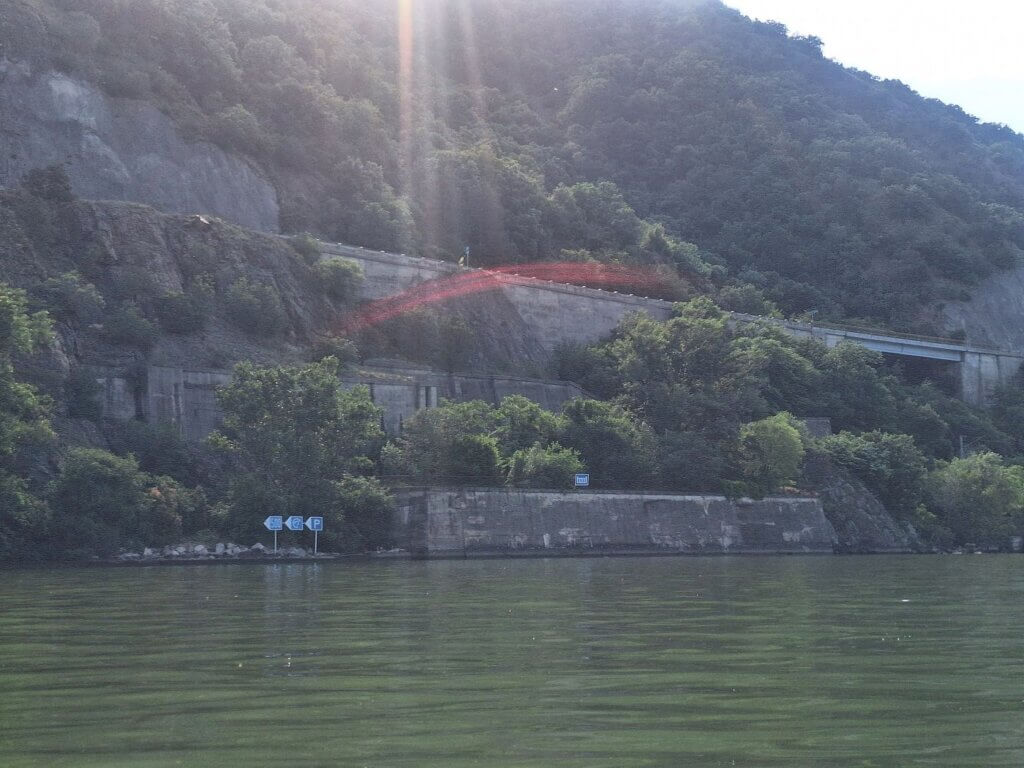

Once we’d crossed back to the left side, we were parallel to the elevated highway between Orșova and Drobeta-Turnu Severin and the desolate train station of Vârciorova. The 35-meter increase in water levels had filled up the valleys with small streams contributing to the Danube. It would be possible to paddle into those inlets in our kayak. The train bridge is closer to the water level and leaves a small gap for small boats to duck under.

We were looking for a suitable spot to land and pee before we’re hanging around the lock for several hours in the sunshine. Toilet opportunities will be even rarer there. We eventually found something good enough.

On this side, we came across two lights that probably tell ships at night they’re approaching the dam. There was also the inland waterway sign for dam or weir. We haven’t seen that one in a long, long time.

The Romanian side of the Danube had a very artificial embankment full of concrete breakwaters. I think the Serbian side is the same, but I haven’t seen it up close. Above the Romanian breakwaters were the train tracks and above those the road for cars and trucks.

For funsies and to let the world and the lock operators know where we are, I turned on our tracker in the OnCourse app by MarineTraffic. Perhaps they could see our approach and see what kind of ship we are. Our profile on the app isn’t perfect, but it is something we can broadcast. I left it on for a few minutes.

The current suddenly picked up. This was our biggest surprise of the day (yet). We were grateful, but also a little concerned. Are the water levels so high that the dam is overtopping and the top layer of water we’re paddling in is actively being dragged out?

The Luckiest Timing in History

As we got closer to the dam, it went from Standard Definition, to Full HD, 4K, and finally 8K. We could see the Romanian control tower, the dam to the right, the space to the left that’s just floating river debris, and the lock hole. It was almost 10:00. It was time to give the lock HQ a phone call to tell us we’re coming. Jonas tried first on his phone, but he couldn’t get through. Then I called a couple of times, each time hung up on because the line was occupied.

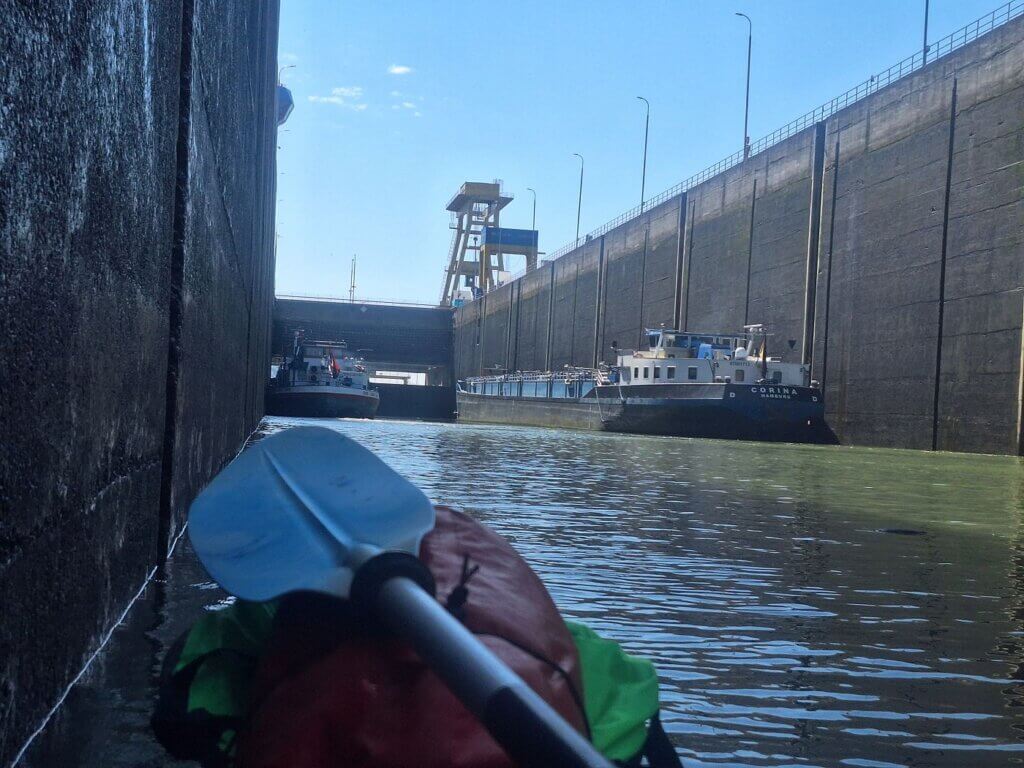

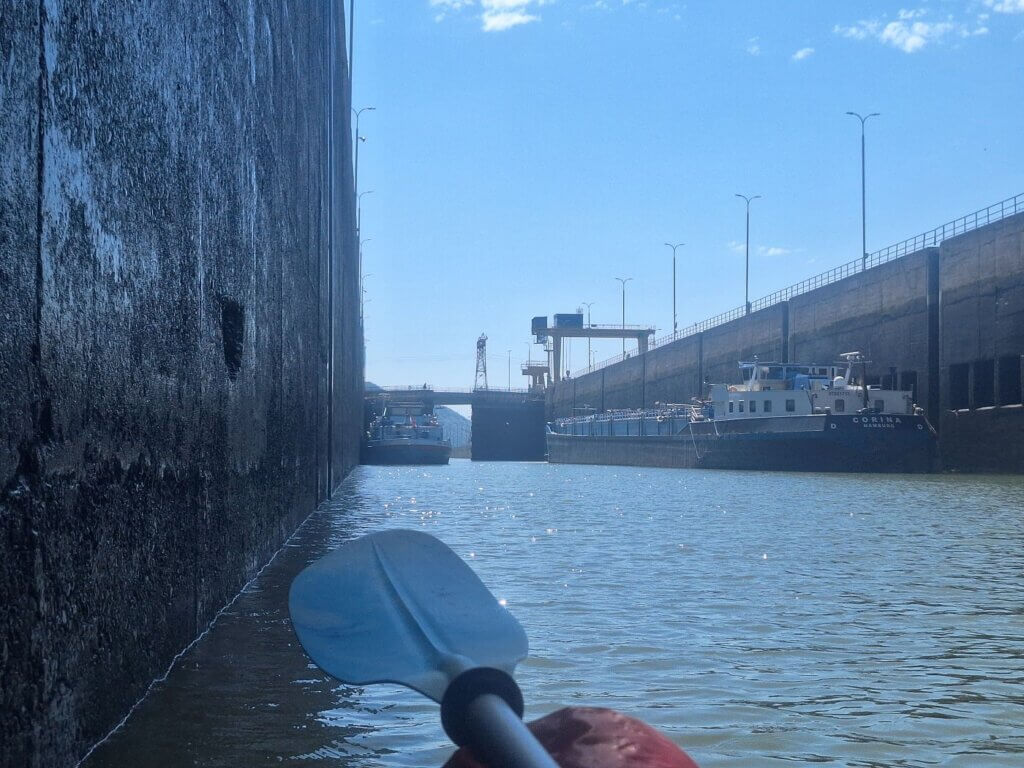

There were one, nay, two ships in the Vorhafen (outer harbor, or ‘pre-harbor’). One of the ships looked like the empty cargo ship I’d seen traveling downstream two-and-a-half hours earlier from Orșova Two red dots in the distance indicated that we couldn’t approach the lock. Are these fellas going downstream, per chance?

After trying to call the lock operators a bunch of times again, each time with no luck, my next idea was to get parallel to the wheelhouse of this German-flagged ship called Corina based in Hamburg on the right. As long as we were safely on the far left side of the outer harbor, we could maybe wave at an actual human and ask them to radio control to tell them there are two humans in a tiny kayak. Something like that. I am improvising.

As we got alongside, we saw one guy walking on deck. He shouted something, probably for us to stay back. We shouted something in German about can we go in with you. At least we’d been noticed. But now we’d really like to know how to proceed from here.

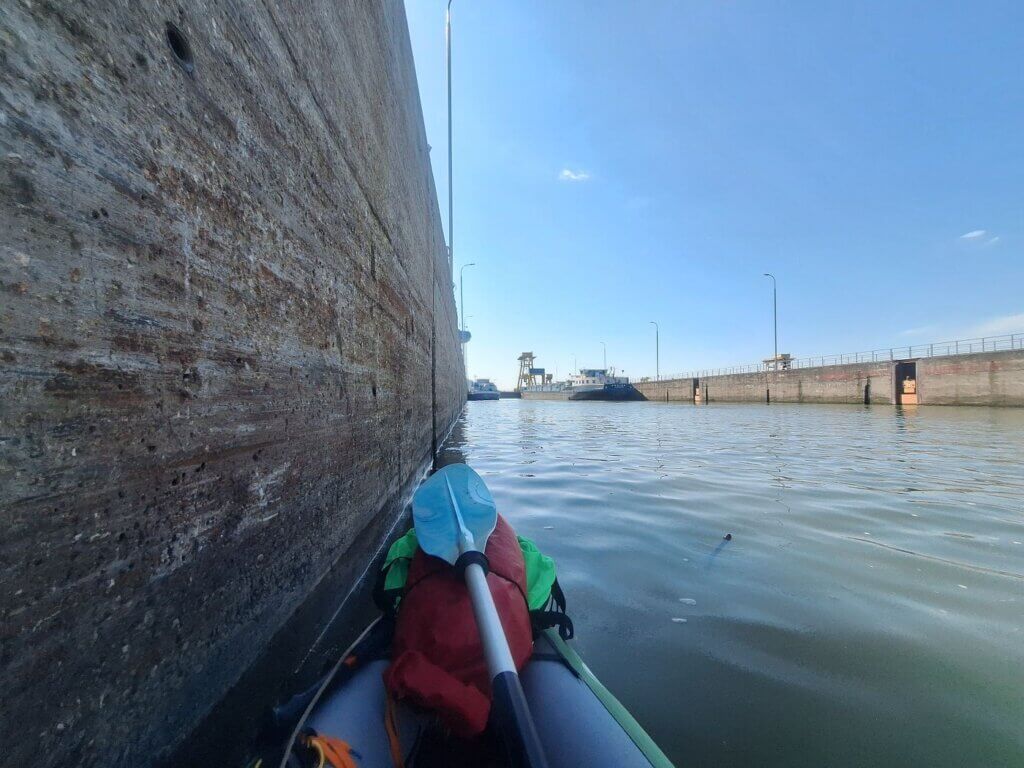

I tried calling again, but I was actively pushed away. The lights on the lock gate turned green. The smaller ship in front of the German ship with the Serbian flag motored in. The German ship turned on its engine with a big blast of black smoke and the guy on deck cast off the moorings. They motored in as well and we tried to match their pace. The guy on deck we’d shouted with before indicated us to stay back, stay back. And stay on the left side of us.

We stayed back—or so we thought. We tried to follow into the lock behind them, as this felt like such a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Damn, if they still kick us out now, then what?

There was a guy from the lock operations on the Vorhafen jetty to the right, the Tito monument with the Yugoslav flag on the Serbian side. He definitely saw us but didn’t give us any instructions. So… we just paddled towards the lock.

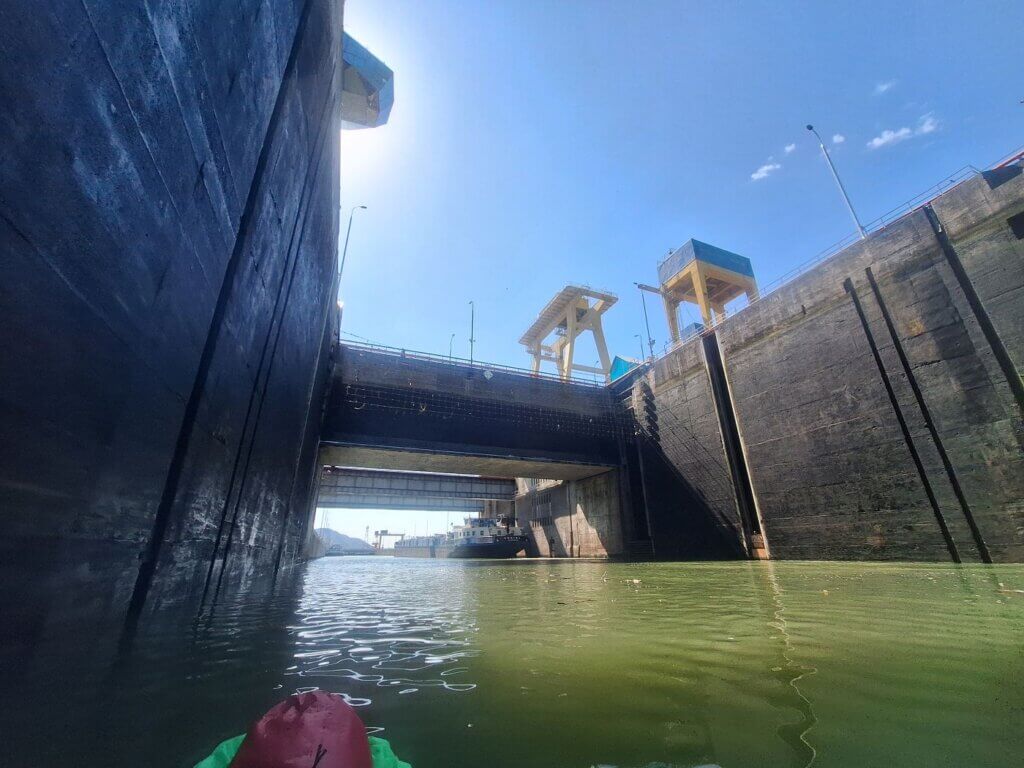

Some guys appeared on the left-hand side far above us. One of them tried to talk to us, but he didn’t speak German or English. But we could do this by just following him. We passed some kind of mechanism in the walls, which was probably the system to close the locks. Otherwise, it was really disorienting and hard to see where the lock actually began.

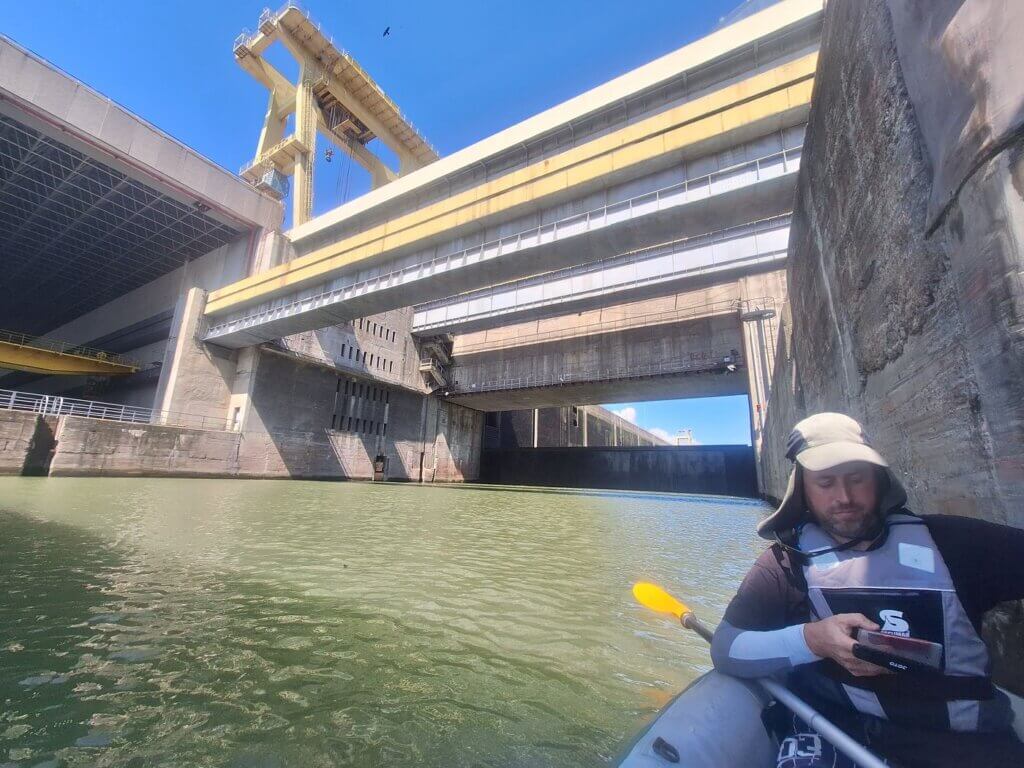

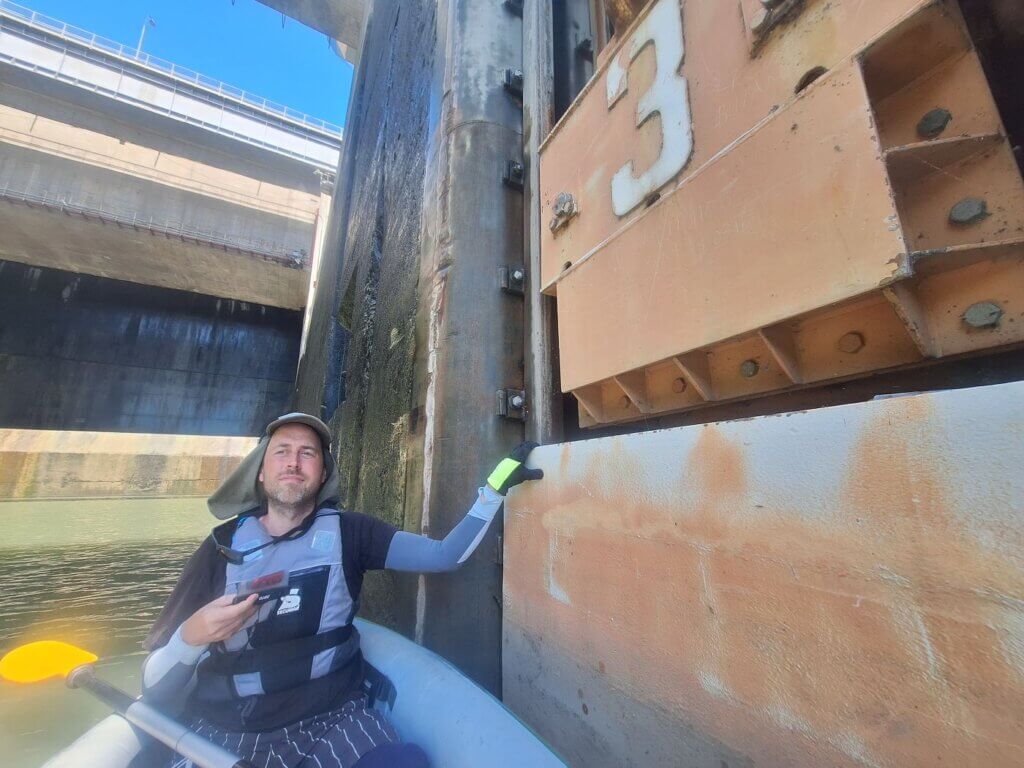

Meanwhile, the Serbian ship had moored all the way at the front of the lock on the left-hand side. The German ship was in the process of mooring on the right-hand side. They turned off their engine. And the guy above us told us to continue, past something that said 1, followed by a ladder. We continued… to another yellow thing that said 2, then past a ladder, to continue… He asked something, and I showed him my boat leash as the only thing we could use to attach us to something.

At yellow mooring site number 3, we were told to stop. He asked if we can hold on to it, and we both reached out and held it. Jonas asked something about if it has something to do with the waves in the basin, but the guy disappeared.

I guess we can join the fall with the big ships?

We took some photos and videos, when suddenly a wall appeared out of the water behind us. Ah, that’s how it works? Slowly but surely, this wall made the Danube behind us disappear from sight. The Serbian ship in front of us still had its engine running, kicking up some water.

The yellow thing Jonas and I both held onto suddenly started to drop, slowly and bit-by-bit.

This is actually happening.

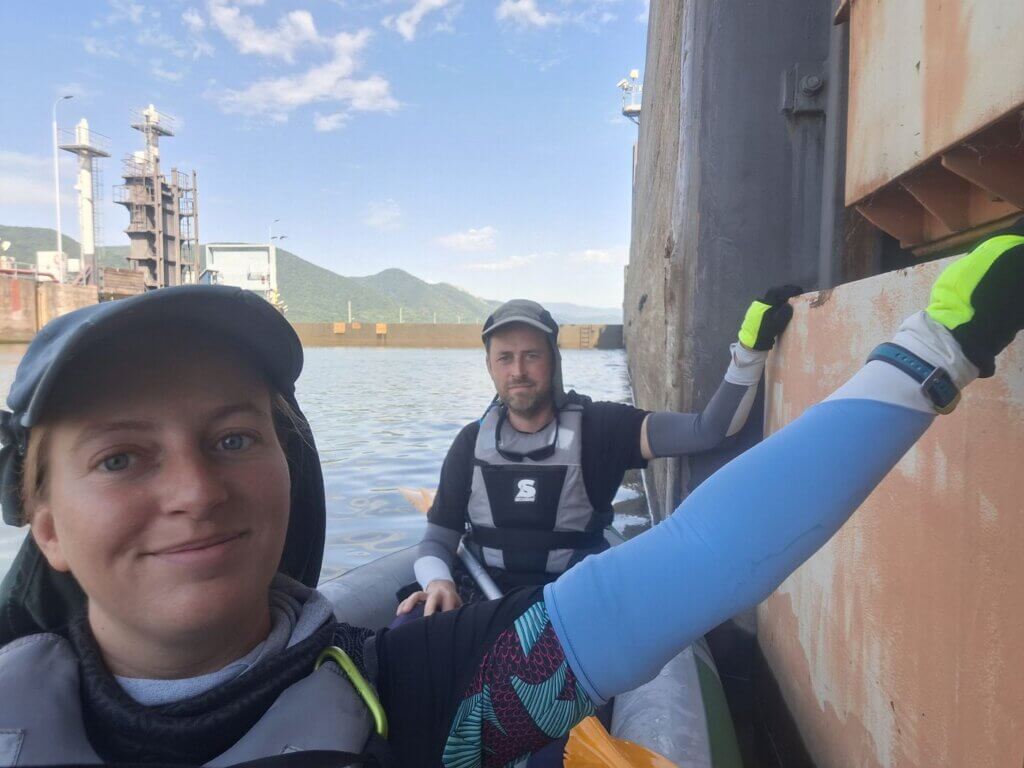

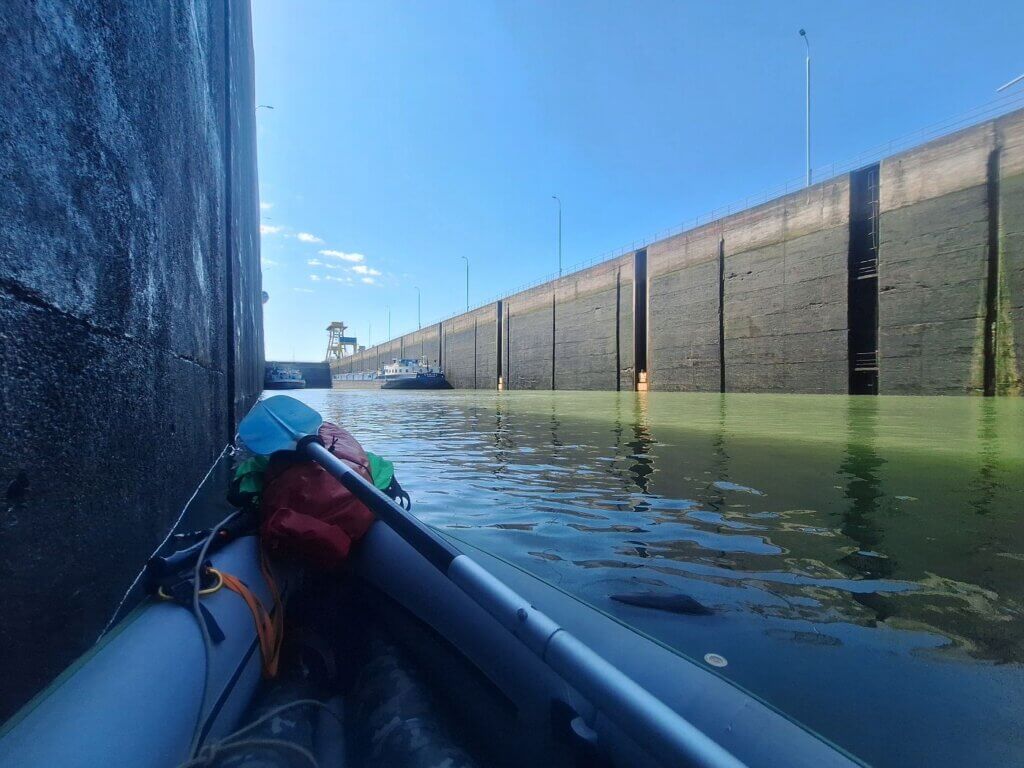

Iron Gates I Lock: A Two-Stage Descent

We began our fall in the first lock at 10:09. It was a little spooky to hang on to the 3rd mooring spot that moved down with us. We both wore gloves on that hand to protect it from dirt and the constant pressure of the edge. There were no waves in the sluice basin. It was basically just a slowly-draining bathtub. I had no fear of being sucked away into the great unknown, because when Zucchini doesn’t leak, she’s a wonderfully buoyant vessel.

Jonas pointed out to me how this mooring thing actually worked. Above the number 3, there was a mooring bollard. Big ships like the Corina moor themselves to two or three of these to keep their ships attached to the walls. And then this mooring bollard descends with them. The place of attachment is a good height for a big ship, but it’s way too high for a small kayak like us.

It was quite a slow process, but going through the Iron Gate I lock as a kayak wasn’t boring at all. It was definitely crazy how high the walls towered above us. How much further down will we go?

At some point, I noticed the red graffiti in the lock basin on the other side. I first read the П[у]Т[и]Н ХУЙЛО before I also spotted the РУССКИЙ КОРАБЛЬ [bollard number 6 gap] ИДИ НА ХУЙ!

Nice. People of culture. I agree with the sentiment. No porkies were told.

People were walking around up on the edge. Hydroelectric powerplant employees, I presume. Ahead of us is the bridge that passes over the lock and the entire dam. The only time we could see traffic crossing from Romania to Serbia via the dam was when something tall like a bus passed. We were literally in too deep to see most of the time.

A heron sat on the edge of the wall, staring down into the abyss, looking for a fishy snack that might have gotten trapped with us.

Behind us, a concrete and not-movable wall appeared. This indicates the maximum draft a ship can have when entering the lock. The moveable wall was now visible behind us. Are we almost there yet?

At 10:50, the sky appeared beyond the Serbian ship. The lock gate on that side was slowly lowering. My arm was a little numb, so I asked Jonas if I could let go for a second to shake the blood back to my fingers. He had no trouble keeping us in place with one arm.

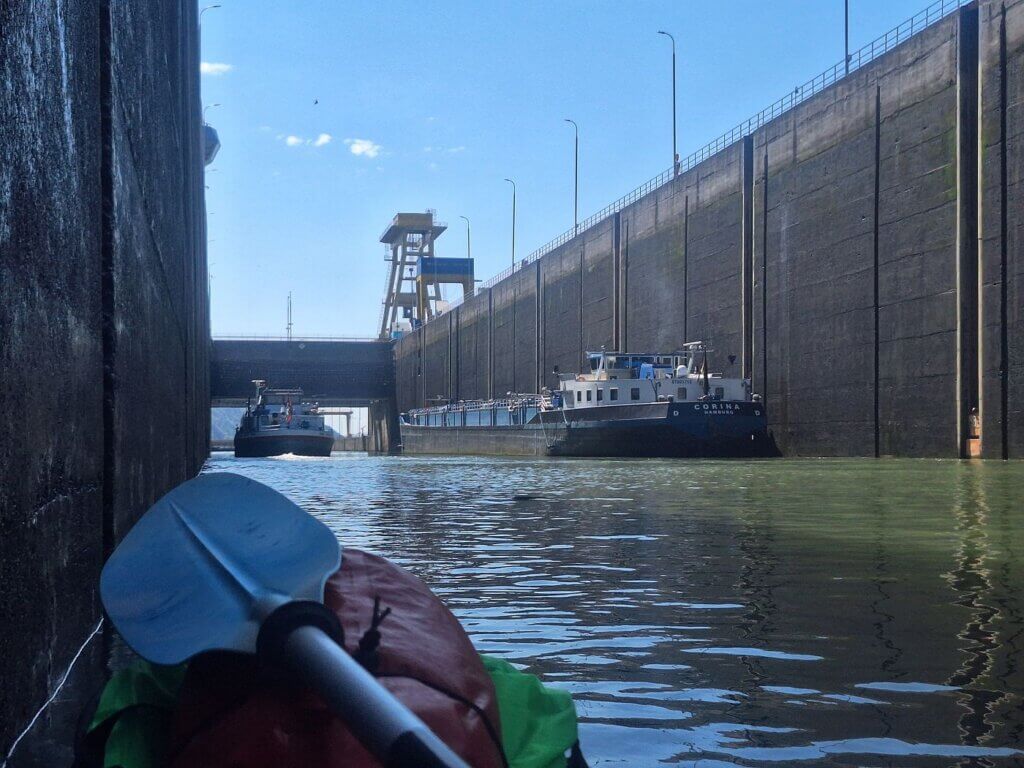

At 10:55, the Serbian ship cast off its moorings and motored into the second lock. The Corina turned on its engine at 10:58 and followed the Serbian ship. This was our turn as well, and as if we were part of a royal procession, we kept the same distance from the Corina as our mooring spot, matching her pace. It was very slow, so only one of us had to paddle. I had no idea how much we’d descended, but it must have been at least 20 meters.

We passed below the shiny glass control tower and under the road bridge that crosses the lock. The last mooring spot was number 23. There was a kind of weird net hanging above the lock water right before we passed under the bridge. This is probably to make sure that none of the ships are tall enough to hit the bridge.

During our paddle into the second stage of the Iron Gate I lock past the gate, I realized how nasty the almost-drained water was. Besides trash, we kayaked past the corpse of a dead baby bird. It was a rather big bird that was pale and had been in the water for quite a long time. Gross.

The second stage looked different. We could look into the mechanisms of the dam’s turbines to our right. There were many small bridges that crossed the lock. I expected someone to come talk to us again on this side, but we just paddled in all alone, found number 3 on the left side again, and held on at 11:06.

All this time spent in the lock so far made me hungry, so I held on to the mobile mooring spot while Jonas grabbed our protein bars. Behind us, the gate closed at 11:10. The descent began. This time, it all went a lot faster.

I don’t know why or how! Perhaps the lock operators were like… they know the drill and were good, so we can go at normal speed now? Like I said, I don’t understand why this was much faster. This time, there was also water spraying behind us, although it didn’t disturb the water around our kayak. The ledge for maximum ship depth was quickly visible.

The total fall was also a little less high, maybe 10 meters instead of 25, but that didn’t fully explain why the front gate swung open at 11:26. Our descending number 3 even went a little back up, though there were no waves to speak of.

It’s funny how none of this was as scary as I thought it would be, because the basin is quite wide and are not descending to the center of the earth, blocking out the sun. It wasn’t claustrophobic. Having watched the video from the Serbian guy during the TID’s descent in this lock, going in with a hundred other kayakers seems like the bad deal. They kind of have to chain up on each other since there’s not enough numbers to hold onto for all of them. And holding the number 3 for 10 kayaks sounds exhausting as fuck.

The Serbian ship didn’t stick around and motored out rather quickly. The German ship swiftly followed, and we matched their pace.

Jonas took some photos and videos when we got out and I paddled to keep up. Then we switched. We paddled past the exit gates and under the other service bridge and then… we were in the Vorhafen on the other side.

It was like I blinked and I couldn’t see the Serbian ship anymore. The Corina also seemed to be in a hurry, as she was so far ahead of us already. Being in a kayak truly is that slow, apparently. Farewell, fellow sluice mates.

On the left ramparts outside of the sluice were three men employed at the dam. One of them took a picture or video of us as we kayaked out. We waved at them.

Water Police in Drobeta-Turnu Severin

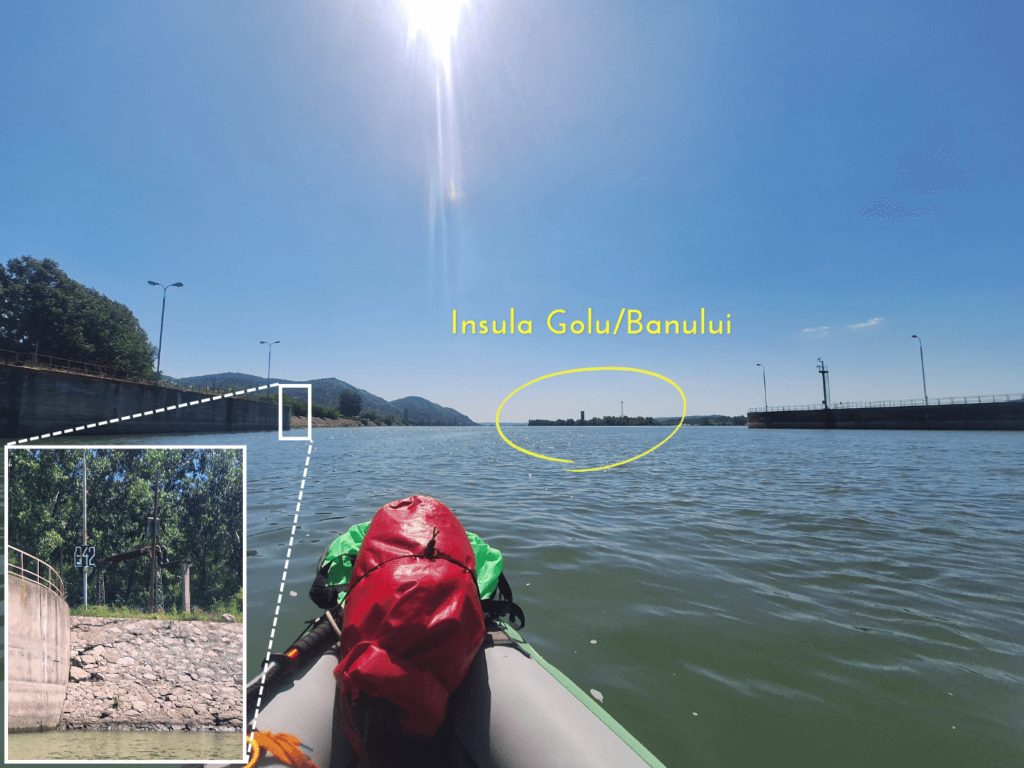

It was 11:45 when we exited the Vorhafen from the downstream direction. There was lots of interesting graffiti on the walls all the way through and some moored ships that were in a poor state. To our left was the maze of electricity cables from the dam, that from hear fan out across the mountains to Romanian towns and cities to power them.

Ahead of us was Golu island, also known as Banului island. Some electricity lines crossed the river via it. The two ships we’d shared a moment with were long gone and nowhere to be seen.

Behind us was the entirety of the Iron Gate I dam. We could now see where the water spills over the dam when it doesn’t go through the turbines. Most sections were dry, except for two narrow ones. We were easily two kilometers away already and the whole structure didn’t look that big from here anymore. I tried to identify the lock entrance on the Serbian side, but it’s all too far away.

A ship called Adonis zipped past us upstream. Once we passed the inlet of the Jidoștița River, our paddles gained traction in the current. So far, we’d mostly felt like we’d paddled against the current. And now, we were finally in it. Wheee!

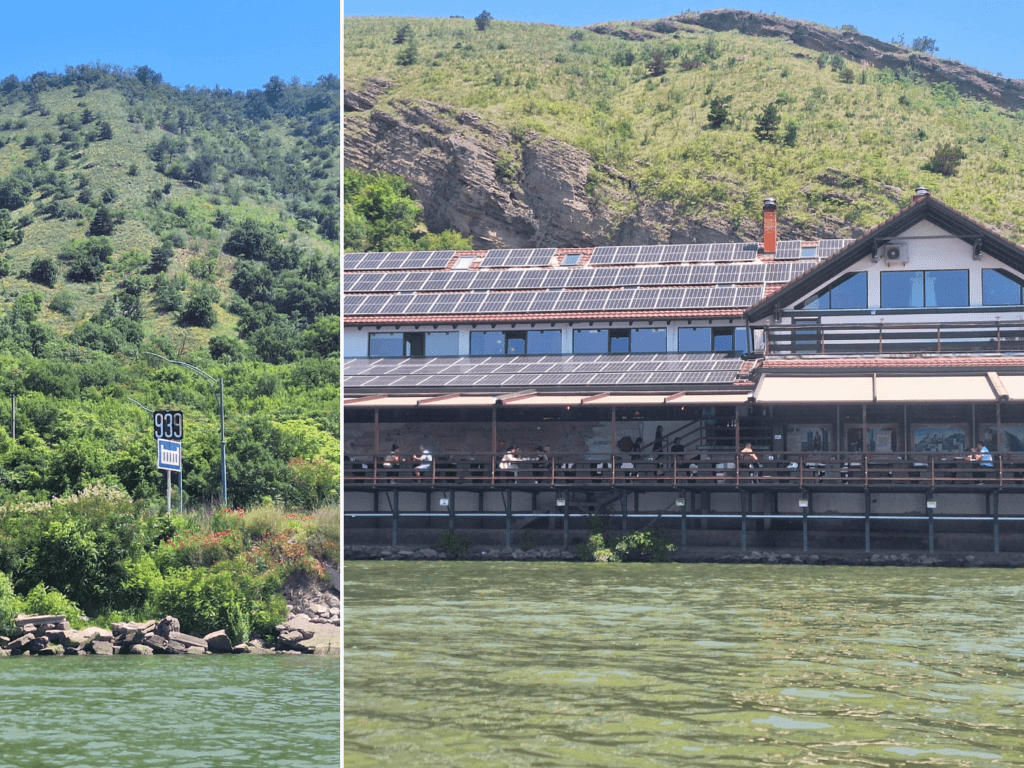

We made some good progress downstream and spotted the dam sign at kilometer 939. But we also needed to scout for places to relieve our bladders once again. While there were secluded areas on the Romanian side, it quickly changed back to populated riverside restaurants, industrial areas, or parking lots next to gas stations. Jonas found a spot and we made a quick break. Then we continued a little again before we stopped for my needs after a cargo ship passed upstream. Privacy is needed.

It was time for the sandwiches. One of us paddled while the other one ate. Even though the current was good enough for the both of us to eat at the same time while floating lazily, I still think this is a best practice, also for situational awareness. We passed the equivalent downstream lights and navigation signs at kilometer 936.

Across the river on the Serbian side are shipyards, ship launches, and the 16th-century Ottoman fortress of Fetislam right before Kladovo. Though I visited Kladovo with a long-time friend back in 2015, I don’t remember visiting the fortress, or anything in particular. The memory of that time is incredibly fuzzy.

We were now parallel to Schela Cladovei on the Romanian side, which marks the start of the shipyard of Drobeta-Turnu Severin. We passed some spectacular rustry cranes, moored ships carrying buoys, and anchored barges in the middle of the river. An Austrian pushtow called Ybbs was moored at the shore. Some guy threw out some food scraps into the Danube from the window. Luckily, we weren’t close to that ship.

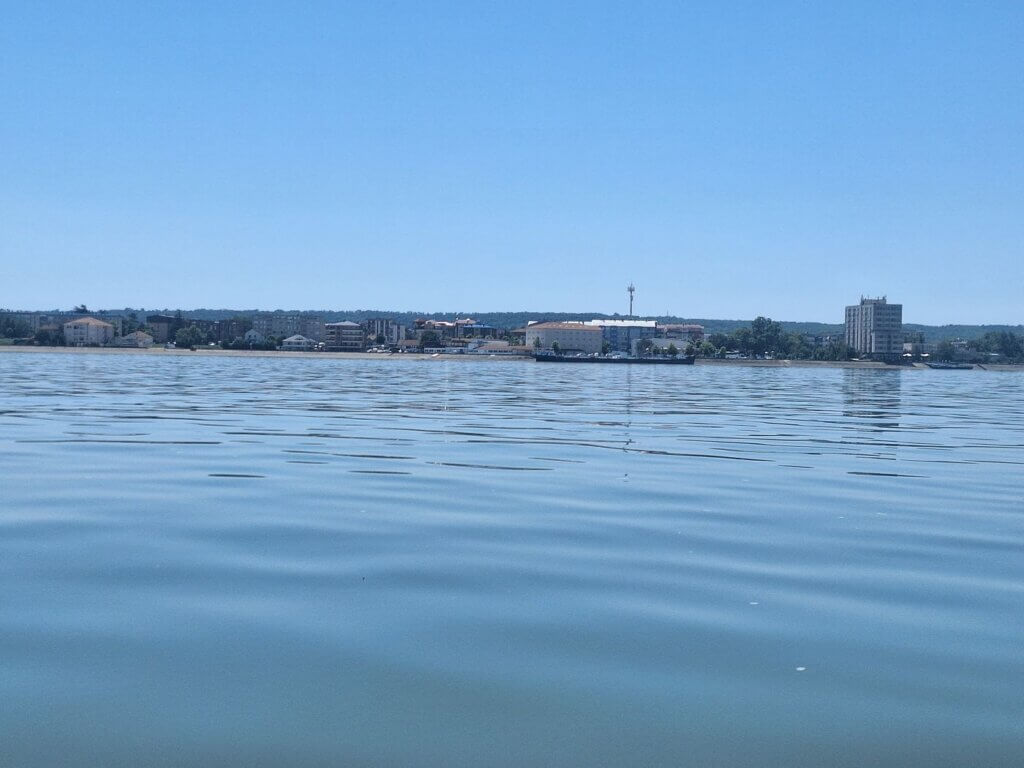

Across the Danube was Kladovo, which looked very idyllic and pleasant from here, with a beach or nice embankment. Like, I know there’s broken glass there too, and probably too many fishermen, but I wish I had the freedom to just paddle to that side, land at a restaurant, and have a great Šopska salata.

Ahead of us was a small motor boat, dark blue. Police? As they approached us slowly and then suddenly stopped to lie in wait, we knew they were Romanian water police. This is the third fucking time they just want to talk. I will let Jonas do the talking. We stopped paddling to slow down our approach.

Two guys, neither old nor young, came alongside us at 13:33. They asked where we came from and where we were going. Jonas answered the questions, but it wasn’t enough. They wanted to see our documents. Jonas got his yellow dry bag out while I held on to the little motorboat. Not too close to it, not too far from it. I hope Zucchini won’t get damaged from this close encounter.

Jonas handed over our passports inside their zip lock bag. Hopefully, they will treat our precious documents with care.

It took a few minutes while the guys checked our passports. For the rest, they didn’t need to know anything else, such as where our journey takes us. We slowly drifted about 200 meters with them downstream as the current was still quite good here. I checked the map to see that we were less than 1.5 kilometers away from our landing spot in Drobeta-Turnu Severin. This is quite messing with the good vibes we were enjoying.

At 13:37, we were free to go. Jonas got the passports back in the zip lock bag. We said goodbye. One kilometer later, we paddled past their spawn point at the port of Drobeta-Turnu Severin.

We approached the restaurant zone. Here is where we shall land, preferably at a restaurant close to the ruins of Severin Fortress. Jonas found a suitable spot and guided us there between two restaurants with quite some customers. Arrival time: 13:50. Time to drink a beer while the boat is drying.

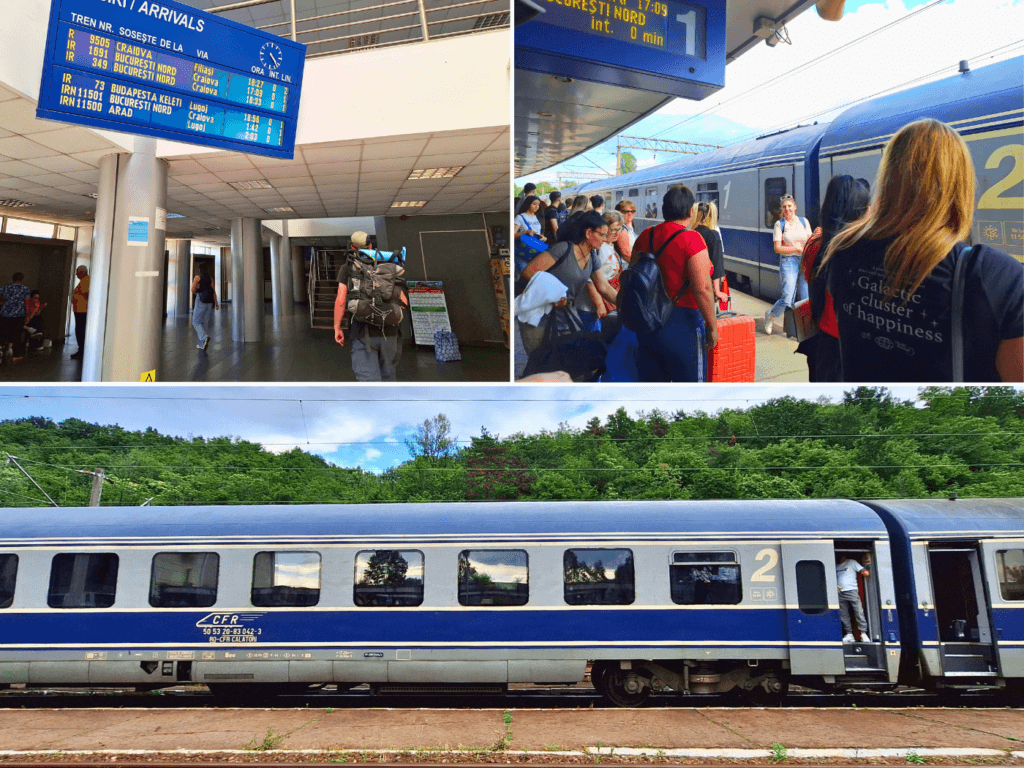

The Train from Drobeta-Turnu Severin back to Orșova

I checked out the restaurant Terasa Marinaru. We made a plan to dry the boat on the concrete embankment below the restaurant. We could keep an eye on the boat from a table. It was very hot and sunny, so Zucchini will be dry in no time.

We both got changed into our land clothes and shoes. When we sat down, the owner walked by and said he’s also a kayaker and used to be on the national team. He said we’re welcome to keep our kayak here during our five-day stay in Drobeta-Turnu Severin, which isn’t starting today, but two days from now. Confusing for all of us, I know.

We tried to explain that Zucchini is inflatable and we will put her in a backpack. This was hard to communicate.

While we ate some cheese fries and drank some beer, a cat showed up. This big boy is a regular of the restaurant and the owner told us his name is Mafia, because he beats up dogs in the area. Accused of racketeering? I say Mafia is innocent of all charges. Just look at his face.

We also watched the ship situation on the Danube. The Ybbs and its trashy personnel had grabbed some barges and began its journey downstream. The Corina made a sail-by, going upstream, still looking empty as ever. Is she going through the lock again? Why?

Afterward, we packed up Zucchini. She was very dry, probably the driest she’s been since we restarted this trip. I didn’t want to arrive at the train station too late, so we left one hour in advance to walk the 1.2 kilometers to Drobeta-Turnu Severin train station. At the fortress, people were refilling large water bottles with fountain water. Is this a sign that the tap water in this city is not drinkable?

At the train station, we bought tickets to Orșova. It was 17.50 RON per person, which is about €3.50. Then we still had to wait quite some time before the train showed up. I had a nap on Jonas’ shoulder while we waited.

The train ride back to Orșova was very interesting. I was mostly looking out the window to see the dam from a different angle and to see the ships that had just passed through the Romanian lock traveling upstream. Some of the railroad bridges didn’t feel that… stable. One of them at the stream of Râul Târziului near Ada Kaleh felt like it was trying to drop our train into the Danube. A bit scary.

Once at Orșova train station, we tried to get a taxi. One guy said he would be back, but 20 minutes later, he still wasn’t. We then called our host to find us a taxi, since we had tried to find the phone number of a(ny) taxi driver in Orșova online the day before this trip without success. He called one, who showed up not much later.

While driving, we put on our seatbelts and he laughed at us, saying we don’t need to do that in Romania. We haha’d it away but kept our seatbelts on, because duh. When he dropped us off at our apartment, Jonas asked for a quote to drive from here to Drobeta-Turnu Severin in two days. He said it’s 100 RON, which we thought was fair. So Jonas asked for his phone number and arranged the ride for two days from now, also messaging in between to confirm…

Maybe the back-and-forth was very silly, but there was no guarantee we could have gone through the Iron Gate I lock at the time that we did. I still think we were impossibly lucky at such an important moment.

What a happy kayaking day.

Five Days in Drobeta-Turnu Severin

I know it’s a little messy with the back-and-forth traveling between Orșova and Drobeta-Turnu Severin, but the Orșova chapter is now concluded. When we returned to Drobeta-Turnu Severin on Wednesday by taxi, this is how we spent the five days in this part of Romania.