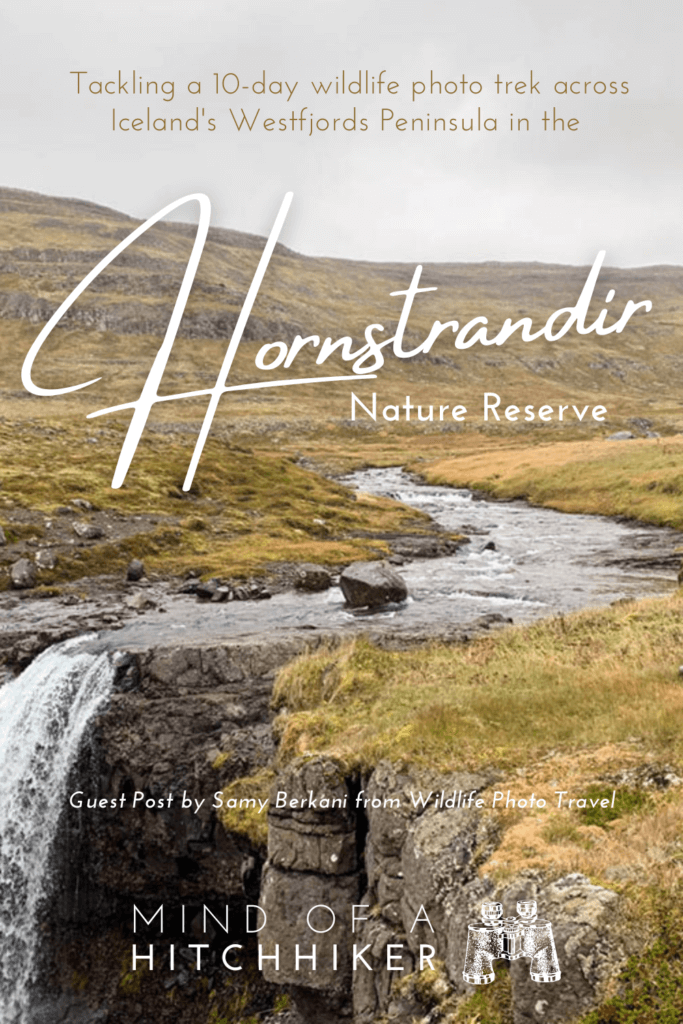

Hornstrandir is a nature reserve in northwest Iceland. It is an isolated peninsula once inhabited by humans. Now deserted, it has become a paradise for experienced hikers and the kingdom of Icelandic Arctic foxes. I discovered this nature reserve when I started taking an interest in one of the smallest canids in the world, the Arctic fox.

I’m a wildlife photographer. For several years, I’ve been working in the Hornstrandir reserve as a hiking and photo guide. Every year, I organize an Arctic Fox Photo Workshop for wildlife photographers, biologists, and enthusiasts with a small team.

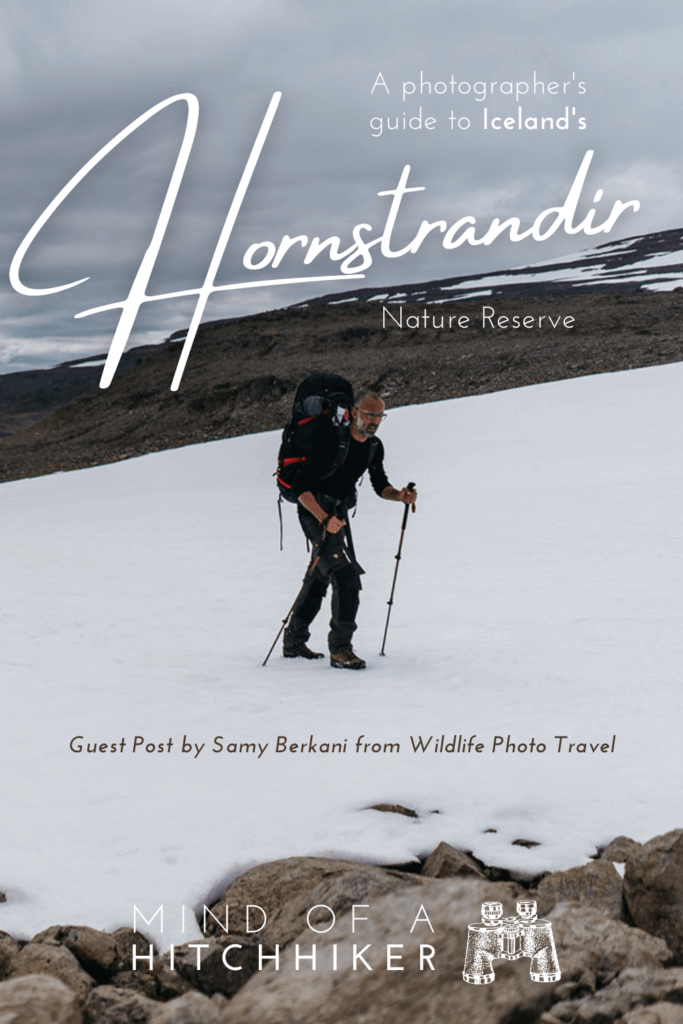

But the story I will tell you today is that of my first long trek to Hornstrandir, on a very little-used route. Indeed, before joining the reserve’s classic route, I chose to cross the glacier Drangajökull from west to east before heading north. For this adventure, I asked my friend Urip, who is also my colleague today, to accompany me. He’s a landscape photographer with a wealth of experience in cold, mountainous areas. There weren’t too many of us to look after each other, especially when crossing the glacier, Iceland’s least known and least frequented.

Contents

Discovering Iceland’s tundra

The tundra is a must-see environment. It’s an Arctic biome, with low vegetation, no trees, and very short summers. The wildlife here is rich and fascinating, and I’ll be talking about it later in this article.

Discovering the Icelandic tundra was a real shock for me. I was born and raised in Algeria, a very hot country, diametrically opposed to Iceland. But I found in the tundra what I loved about the Sahara: wide open spaces, a discreet but rich nature, and a soothing silence.

The Icelandic tundra is made up of fjords, bays, small mountains, deep valleys, marshy and rocky areas. Nature here is colorful, with miniature flora, colorful lichens, and carpets of blueberries as far as the eye can see.

I fell in love with the tundra over 10 years ago, and I continue to explore these lands where over 2000 species of plants and mosses live. It’s always a pleasure to listen to the song of a golden plover, to observe the courtship rituals of rock ptarmigan, or to witness the birth of a new generation of polar foxes.

A trek to Hornstrandir, a physical and demanding adventure

Trekking in Hornstrandir is for experienced hikers only. The terrain is rugged, sometimes even dangerous, the mountains steep and there are many rivers to cross every day. It’s a physical adventure that requires a minimum of preparation and training. This is what we did with Urip before embarking on this adventure.

The mountains of Hornstrandir are not very high. The highest peak we climbed was 450m. But I have to tell you that I was more tired after crossing these small vertical drops than after climbing 1200 m in the Alps. The rugged terrain, the rivers to cross, the scree, and the swamps all add to the difficulty and slow progress. But at the same time, they make the trek much more fun. On our Hornstrandir trek, every day had its share of surprises. So we had to improvise a lot.

By the end of the trek, we could barely walk. We were exhausted, but happy to have seen the adventure through to the end.

For the sake of hygiene, dry toilets are available in every Hornstrandir camp. However, there is no possibility of taking a shower. During this trek, we washed in the rivers. Needless to say, a simple cat toilet was sufficient, given the temperatures (the water was between 2°C and 4°C).

Highlights of our Hornstrandir trek

Telling the whole story of this trek would take a long time, as it was so full of adventures and surprises (good and bad). But I’ll tell you about the main stages, from crossing the Drangajökull glacier to the incredible Hornvik peninsula, with its panoramic view that stretches as far as Greenland (just 290 km away), via the Reykjarfjörður fjord and its unique swimming pool.

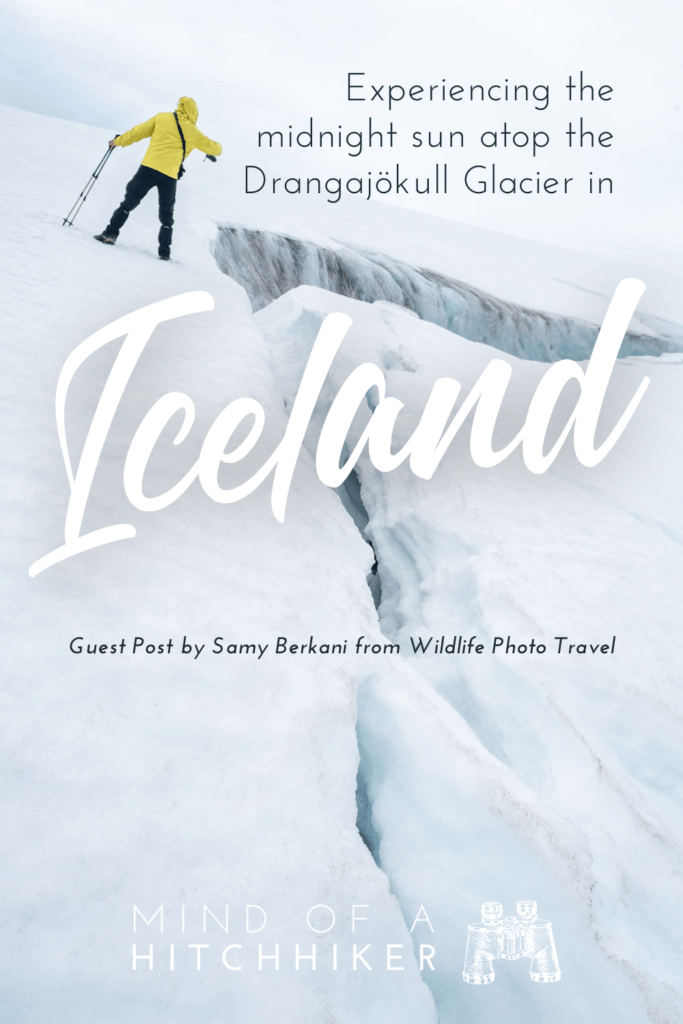

Crossing the glacier

The Drangajökull glacier is located in Iceland’s Westfjords. It’s little-known because it’s located in an isolated region. We spent a lot of time looking for information, maps, aerial images, and so on. And it has to be said, we didn’t find much material. But we had the intuition that it was possible to cross this glacier with only crampons as mountaineering equipment. Therefore, we decided to go for it. We had the necessary experience and skills, so it was safe to try.

We set off from the Kaldalón valley to the west of the glacier. The route we had mapped out would have to be adapted as we went along. After an initial section consisting mainly of scree, we reached the foot of the glacier. We had to climb 900 m to the summit. The task was more difficult than expected and the climb seemed interminable. But we reached the summit, pitched our tent, and enjoyed an unforgettable midnight sun after a good meal.

It’s hard to describe what it’s like to be on top of a glacier. The silence is perfect. Not a sound, not an insect, not a bird singing. You can literally hear the noise inside you. I spent one of the best nights of my life on this glacier.

In the early morning, we had a good hot coffee and breakfast before starting our descent of the glacier. We discovered an area of crevasses and a river under the glacier, which we skirted. Finally, we spent some time photographing the ice and crevasses before continuing eastwards towards Reykjarfjörður.

Hot spring in Reykjarfjörður

After 24 hours on the glacier, we were in a hurry to get to Reykjarfjörður, as we’d heard there was a natural swimming pool in this fjord. We didn’t know what to expect, but the idea of a warm bath was very exciting.

It took us all day to make our way down from the glacier, first through scree and then through swamps. The fjord seemed close at hand, but no matter how hard we walked, we were still a long way from our camp. Around 3 pm, as we rounded a hill, we saw steam rising from a lake. We approached and bingo, a hot spring! But the lake was full of base and seaweed on the one hand, and occupied by dozens of birds (mainly Red-necked Phalaropes) on the other. Urip wanted to continue to the camp, so I stayed behind to photograph the birds. When I join him, I discovered an image I never thought possible in this remote corner of Iceland: Urip lying alongside a 40° pool. Naturally, I don’t hesitate to take off my clothes, wash up, and join him in the pool!

The funny thing about this hot spring at the end of the world was that it was surrounded by Arctic tern nests. And these little birds are very aggressive when it comes to the safety of their young. So we were subjected to numerous attacks and shrill cries, which finally stopped in the evening.

Furufjörður shelter

The next day, it has to be said, we were in no hurry to leave. How could we leave such luxury when we knew there were no other hot springs in the area, and that we were bound to be cold for the next 8 days? We enjoyed one last bath before taking the road towards Furufjörður.

On paper, we were supposed to have a quiet day. We had to cross a first hill, a small fjord, and a second mountain to arrive at Furufjörður after only 12 km of walking. But things didn’t turn out as planned. After the first hill, we discovered a marshy area in the Þaralátursfjörður fjord (good luck with the pronunciation!), land flooded by a glacial river that was overflowing on all sides. So we took off our shoes and pants and crossed the area for 1 km. Once on the other side, we needed to eat and warm up before continuing.

After crossing a second ridge, we discovered Furufjörður, a huge marshy area. At the very bottom, on a dry strip of land, we see a log house, probably a family house, and a shelter. This fjord was inhabited until the middle of the 20th century. We head for the hut where Hornstrandir’s first camp is located. We’re entering the reserve!

Arriving at the shelter, we discovered that it was open. Despite its dilapidated state, it looks perfect for a dry rest.

The small bay of Smiðjuvík

Early in the morning, we could hardly open our eyes – it had been a restless night! We realized (too late) that a family of Arctic foxes had taken up residence under the shelter. The parents’ comings and goings and the fox cubs’ fights didn’t give us much respite to sleep. The icing on the cake was that in the morning, there was no more noise. We couldn’t even see them.

After breakfast, we headed for Smiðjuvík, a small bay on the eastern side of Hornstrandir. I wouldn’t recommend this section to beginners. Indeed, it was a very physical day. We had to cross swamps, climb one pathless mountain and a second easier one, and cross two rivers before reaching the east ridge to see Smiðjuvík camp in the distance. There’s nothing at this camp except dry toilets and a place to pitch a tent. Perfect for us!

The location is absolutely stunning. We discovered this little bay with its steep coastline, black basalt rock, and small waterfall plunging into the ocean. The atmosphere was both dark and peaceful.

At the end of the day, we heard the cries of Arctic foxes. Their silhouettes were outlined on the rocks. I took the opportunity to take a few photos. It was a wonderful experience.

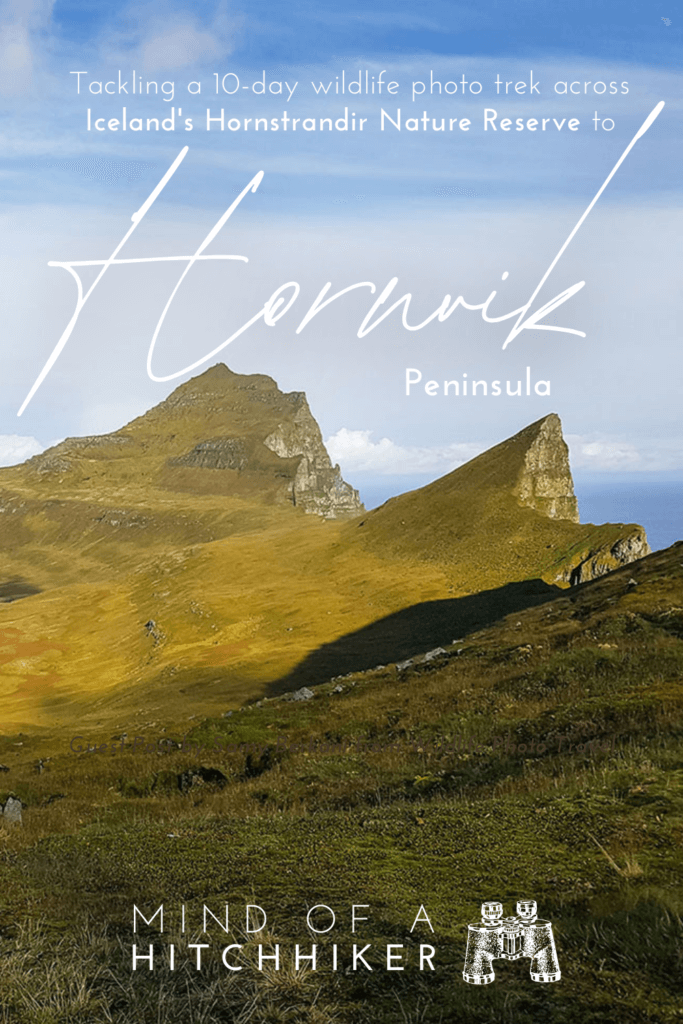

Hornvik, the gem of Hornstrandir

Hornvik is Hornstrandir’s main highlight. It’s the name of both a bay and a peninsula. Indeed, Hornvik means “the bay of the horn” in Icelandic. The place takes its name from the horn-shaped peninsula, which is bordered by the impressive Hornbjarg cliffs.

Walking along the east coast of Hornstrandir from Smiðjuvík to Hornvik was an incredible experience. The cliffs, the mountains, the millions of seabirds, etc., make this one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever seen. Before arriving to Hornvik, we passed by the Hornbjargsviti lighthouse. This place is quite incredible. Lost on the edge of the North Atlantic, this lighthouse was once inhabited by the keeper and is now empty. In June and July, it serves as a stopover for the few hikers who venture out. But unfortunately, it was closed and deserted when we arrived.

As soon as we arrived at Hornvik, no sooner had we pitched our tent than adult Arctic foxes came to check us out. We later discovered that an Arctic fox den was located just 50 m from the camp. We spent the evening watching the fox cubs under the midnight sun. A wonderful time on the edge of the Icelandic tundra!

Hesteyri, the ghost village

The last part of our Hornstrandir trek was the village of Hesteyri. We had planned to leave the reserve by boat from the village to reach the capital of the Westfjords, Ísafjörður.

It took us two days to walk to Hesteyri from Hornvik. As a result, we had to stop off in Hlöðuvík Bay, north of Hornstrandir. This was the easiest part of our trek. Although there were many rivers to cross and steep peaks, the terrain was less rugged and we were able to make easier progress.

To reach Hesteyri, we crossed the Kjaransvíkurskarð ridge and walked along the long plateau leading to the village. At the end of the plateau, we had a magnificent view of the Hesteyri fjord and the village of the same name. We could see a dozen family houses, an inn (The doctor’s house – Læknishúsið), a cemetery, and a pontoon – the only one in Hornstrandir.

The village of Hesteyri was inhabited until the 1950s. At the far end of the fjord, we discover an old Norwegian whaling station, now in ruins. A few meters away, a colony of harbour seals watches us curiously. The atmosphere is quite dark and became even more so when we learned that the horror movie I remember you had just been filmed in the village. If you like to be scared, I highly recommend this Icelandic film.

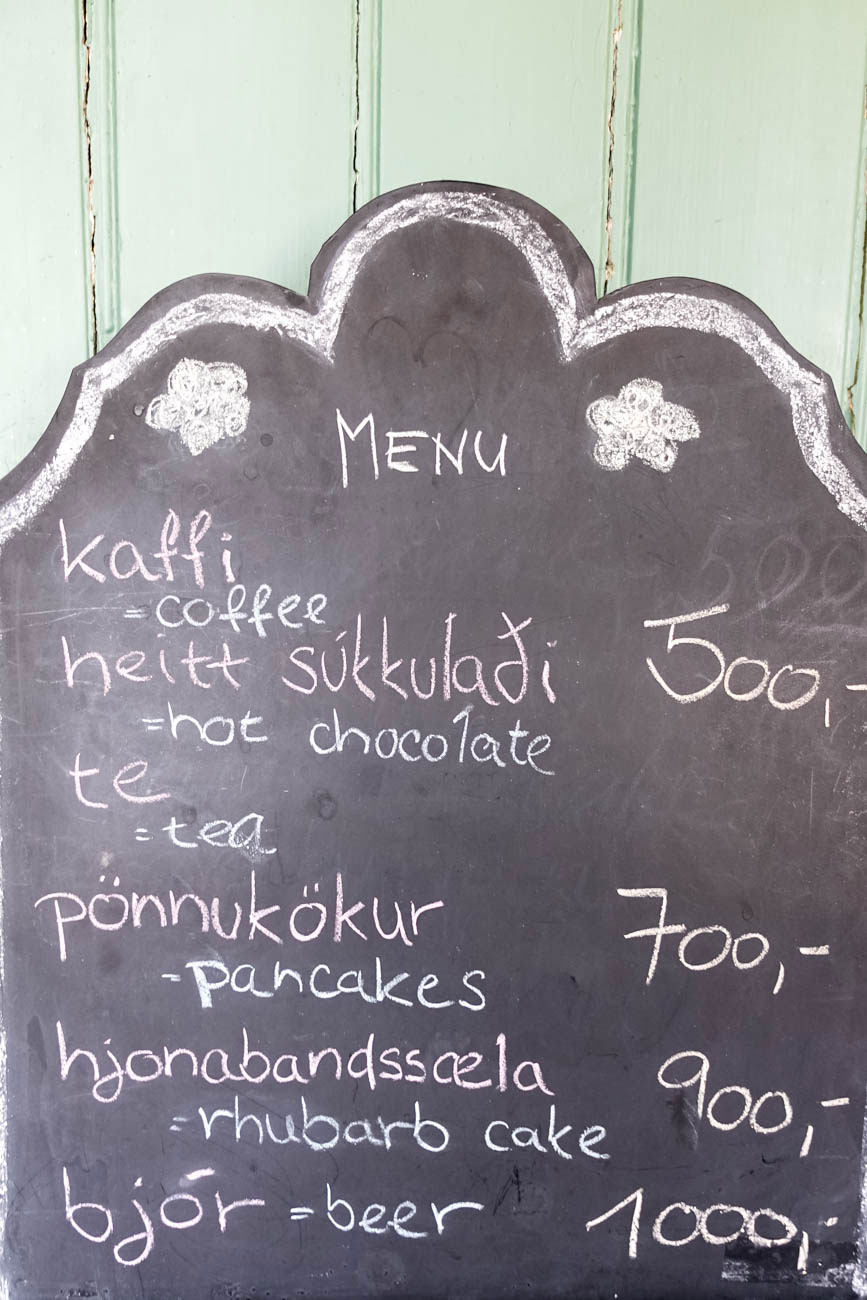

Finally, we ended the evening at the doctor’s house, where we enjoyed some delicious rhubarb cakes and a few Westfjords beers. The next morning, we took the boat to Ísafjörður for a shower and a well-deserved rest!

The wildlife of Hornstrandir

Above all, Hornstrandir is the perfect place for anyone who loves to discover wildlife, feel the elements, and enjoy a unique experience away from the noise of humans. It’s a haven of peace where hunting is forbidden, leaving the animals the chance to live in peace.

The wildlife at Hornstrandir is a glimpse of what our planet could be like if we were willing to share it with other species. Life abounds, in the air, on land, and in the ocean.

If we learn anything from this experience, it’s that nature doesn’t need us – quite the contrary. With us, it’s sick. Without us, it thrives, and enriches itself – it’s a springtime explosion of life!

Wildlife in Hornstrandir has one particularity: there are more prey than predators. Despite the presence of Arctic foxes and falcons, prey is so plentiful that the area remains very interesting for them. The impact of predators is minimal, and all in a natural way.

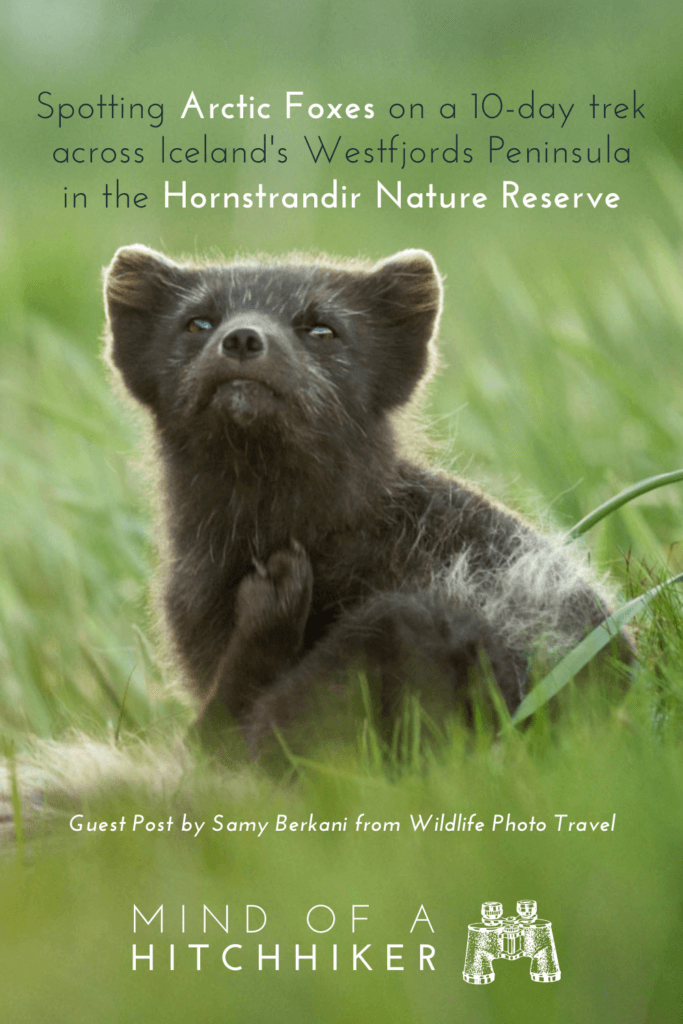

The Icelandic Arctic foxes

Hornstrandir is best known for its population of Arctic foxes. The reserve has the highest density of Arctic foxes in the world. We were able to observe several of them, both cubs and pups, as we were in the middle of the breeding season (June – July).

There are two types of Arctic fox: the white Arctic fox and the brown (or blue) Arctic fox. In Iceland, unlike other Arctic regions, brown foxes are in the majority. But we were lucky enough to see both. We found a magnificent family of white foxes in Hornvik. This family included both parents and no less than nine cubs.

These foxes are champions of survival. Thanks to their thick fur and cold-adapted morphology (small ears, small snout, etc.), they can survive temperatures of -70°C.

In the Hornstrandir reserve, they have no predators, and millions of seabirds within reach. In other words, Hornstrandir is the Arctic foxes’ dream paradise 🙂

Finally, these little canids are Iceland’s only endemic mammal. They arrived on the island during the last ice age, via the pack ice, and remained after the warming, while polar bears and other Arctic animals moved higher up. From a historical point of view, we could call Iceland the island of Arctic foxes!

Seabirds

Hornstrandir is a haven for millions of seabirds that come here to breed every year. It would take a long time to list all the birds we saw on our trek. But the most common are the common guillemot, northern fulmar, black-legged kittiwake, common eider (which is THE Icelandic duck), and purple sandpiper. But above all, we were lucky enough to observe two birds of prey that are rare in Iceland: the white-tailed eagle and the gyrfalcon.

The birds of Hornstrandir are relatively fearless. For example, we spent long moments within 3 meters of purple sandpipers. These little shorebirds are so beautiful! At high tide, they form small groups on the rocks, bury their heads in their plumage, and then look like little balls of grey and white feathers. A magnificent sight to behold.

On the other hand, if you love animals and birds in particular, you need to be prepared to observe nature in its wildest form. Indeed, birds are the first prey of Arctic foxes. We saw many of them die, caught in a fox’s jaws. Needless to say, you should never interfere in such a situation – that’s just the way nature is!

Unfortunately, there were no puffins in the Hornstrandir reserve. And for good reason: they’re very easy prey for the polar fox.

After this trek, we were so frustrated that we went to the cliffs of Latrabjarg, in the southern Westfjords, where we were able to observe puffins and little razorbills.

Humpback whales and other marine mammals

The marine mammal we saw most in Hornstrandir was the harbor seal. These curious little animals came to say hello to us almost every day. But we were also lucky enough to observe several cetaceans. Firstly, a group of orcas in Hlöðuvík Bay, but above all a large group of humpback whales observed at close quarters on our return boat trip. A little further on, 3 Minke whales moved away from us.

Iceland’s Westfjords are a great place for whale watching. In summer, you can even see them from the coast. For example, I once saw a humpback whale from the road as I was driving along.

Hornstrandir in winter

When September arrives, the ferry link to the Hornstrandir Reserve is closed. It is then no longer possible for hikers to get there. Winter sets in very quickly, and the first snow generally arrives in mid-September. This is the period when I guide groups on 12-day treks. These treks are as extreme as they are exciting, and I get to do them every year.

The majority of birds leave the reserve at this time. Only certain birds of prey, such as the white-tailed eagle, winter here. The Arctic foxes find themselves without prey. They slow down their activity and make do with what the ocean throws up (dead fish, crustaceans, etc.). It’s the dearth period!

I was lucky enough to co-organize a winter Arctic fox photo workshop in Iceland. This gave me the chance to experience some incredible adventures in this unique place and to see the life of the Arctic foxes during the mating season, just before spring returns. We’re alone in the reserve. It’s impossible to describe the feeling when the elements are unleashed and only the polar foxes survive. It makes you feel very small but lucky to observe nature in its most hostile form.

Conclusion

I recommend this trek to all hikers and adventurers with a minimum of experience of long, self-supporting treks in cold, wet regions. This category of trekkers can easily make this trek, which will certainly be the experience of a lifetime!

For all others, it’s important to remember that the region can be dangerous, especially if you don’t have the right gear. The challenge, of course, is to keep your clothes dry in these conditions. If you want to do this hike but don’t have the necessary experience/equipment, then the best option is to form a small group and hire a guide.

Finally, if you do decide to visit the Hornstrandir reserve, I strongly encourage you never to interact with the animals, feed them, or prevent the parents from feeding their young in any way. Summer on the reserve lasts less than 3 months, so it’s a race against time for all the animals to raise their young before winter arrives.

In other words, when you set foot in such a wild place, you have to be humble and leave nature as you found it.

I’m Samy Berkani, wildlife photographer, hiking guide and photo guide. I work mainly in Iceland, France and Algeria. I am also the co-founder of Wildlife Photo Travel, which organizes photo tours in remote and wild places.

Through my photography projects and my travels, I’ve accumulated a wealth of experience and stories. I like to share these stories, inform and raise awareness about the nature that surrounds us.