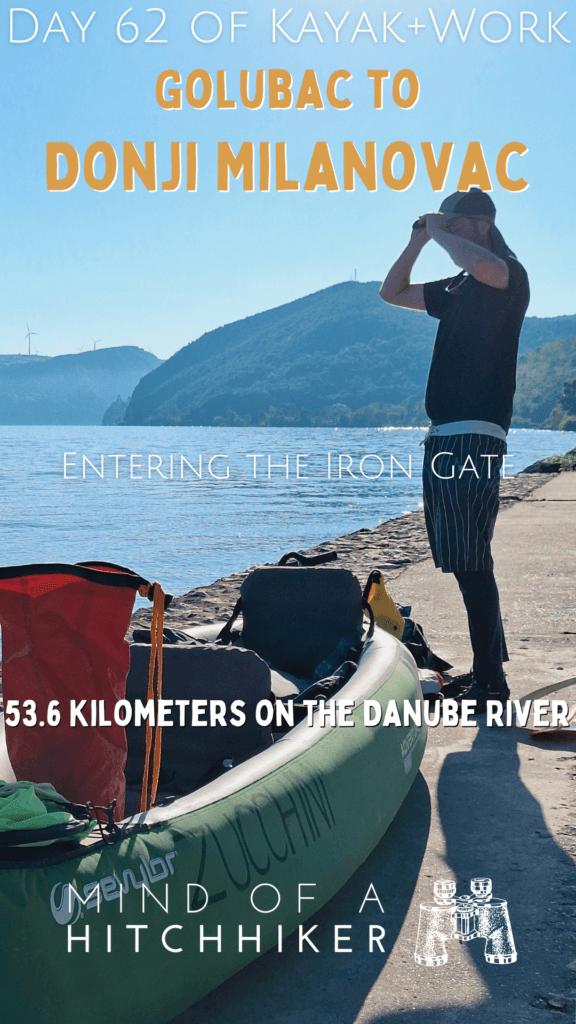

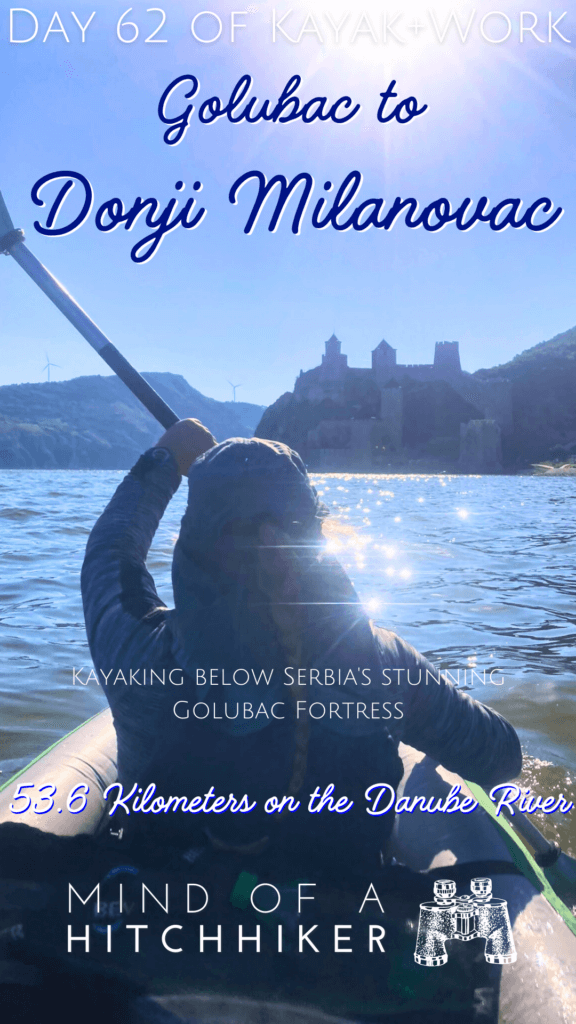

We kayaked from Golubac to Donji Milanovac in Serbia on the Danube on the 11th of May, 2024. This is in the border area between Romania and Serbia through the Iron Gate canyon. It’s the first time we paddled over 50 kilometers in one day.

Want to travel the (entire) Danube River in an adventurous way? Join our Facebook group Danube River Source to Sea: Kayak / Canoe / Bike / Hike / Sail to find your community

Contents

- 1 Seeking a Sailor’s Advice on Đerdap Lake

- 2 Paddling Out to Golubac Fortress + Golubac Gorge

- 3 Canyon Kayaking in the Iron Gate to Dobra

- 4 Theory Will Only Take You So Far

- 5 Tailwind Squalls, Jet Stream Speeds

- 6 1000 Kilometers to Go to the Black Sea

- 7 Arriving in Donji Milanovac

- 8 Miracles: Making the Bus from Donji Milanovac Back to Golubac

- 9 Good info? Consider buying me a Nikšićko!

- 10 Sharing this article? Thank you so much!

Seeking a Sailor’s Advice on Đerdap Lake

Paddling Out to Golubac Fortress + Golubac Gorge

The following morning, we had a coffee and prepared for paddling. It’s not a long walk to our launch spot on the Danube from here and with such little luggage, it was very pleasant.

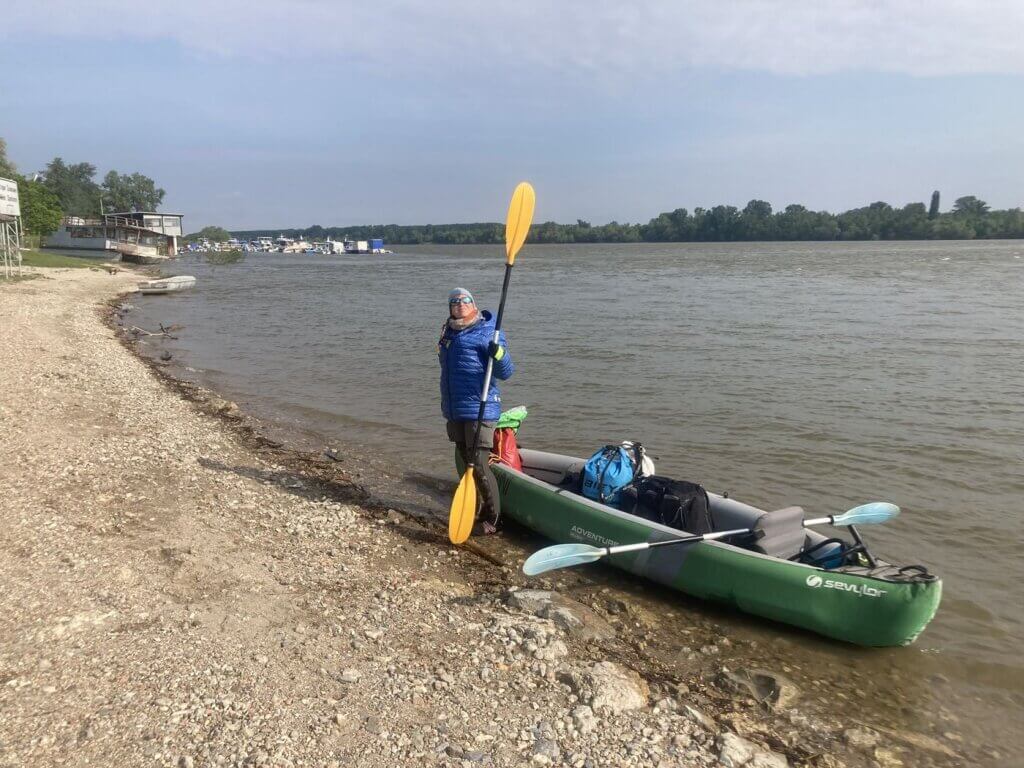

We pumped up Zucchini below the flood protection barriers. The left Boston air vent was leaking for the second time, but with some careful doctoring, we found a way to stop the slow air loss. We departed Golubac for Dobra or Donji Milanovac at 7:40.

I paddled straight for Golubac Fortress a little less than 4 kilometers away. Jonas was adjusting his seat for a few minutes. I had a lot less secondary back support because the two big dry bags weren’t right behind me. When he also got into paddle mode, we were going quite fast.

Closer to Golubac Fortress and the spectacular entrance to the first gorge (Golubac Gorge) of the Iron Gate canyon or water gap, the wind picked up. A headwind, unfortunately. We paddled closer to the land than we wanted. We have to choose between being in that good current one kilometer outward, or not having a strong headwind. I said the current might not help us that much after all because of our shallow draft. The top layer of the water will still throw waves at us.

Near the Golubac Fortress, we took some photos and videos of this spectacularly located fortress. We’ll visit it another day. However, it wasn’t as chill as hoped and the photos were taken against the sun.

There’s a mooring spot at Golubac Fortress for big cruise ships. Supposedly, it also has an immigration office for cruise tourists so they’re in Serbia legally for the duration of their fortress visit. I’m not sure if kayakers can use this to check out of Serbia, but that was one of our ideas had we just kayaked with all our luggage downstream. Either check out of Serbia with the water police here in Golubac or do it in Donji Milanovac.

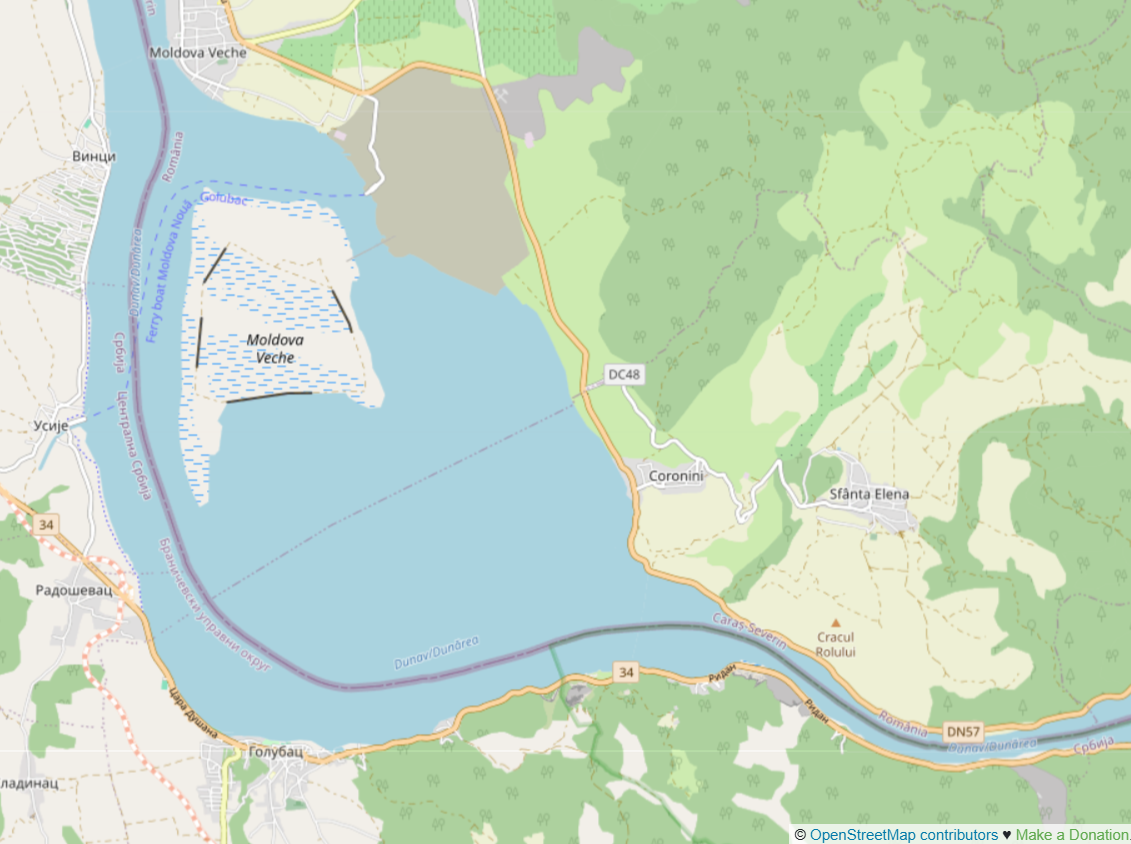

Looking behind us onto Đerdap Lake, I spotted a weird structure catching the light. That’s the Baba Caia Rock, which is a singular rock and forms the outer boundary of the shipping lane, which passes Ostrovul Moldova Veche on its eastern side.

Canyon Kayaking in the Iron Gate to Dobra

Past the fortress, we entered the narrow gap into the Iron Gate. I was hoping for an immediate good current, but right after the fortress is a small widening at the village of Ridan. The headwind was still very strong here and we managed to stay out of the big wave zone by paddling closer to town. Zucchini got quite wet in the splash.

The real narrowing of the gorge began right after that. We headed towards the shallow rocks and managed to push us into the main channel. Finally, current!

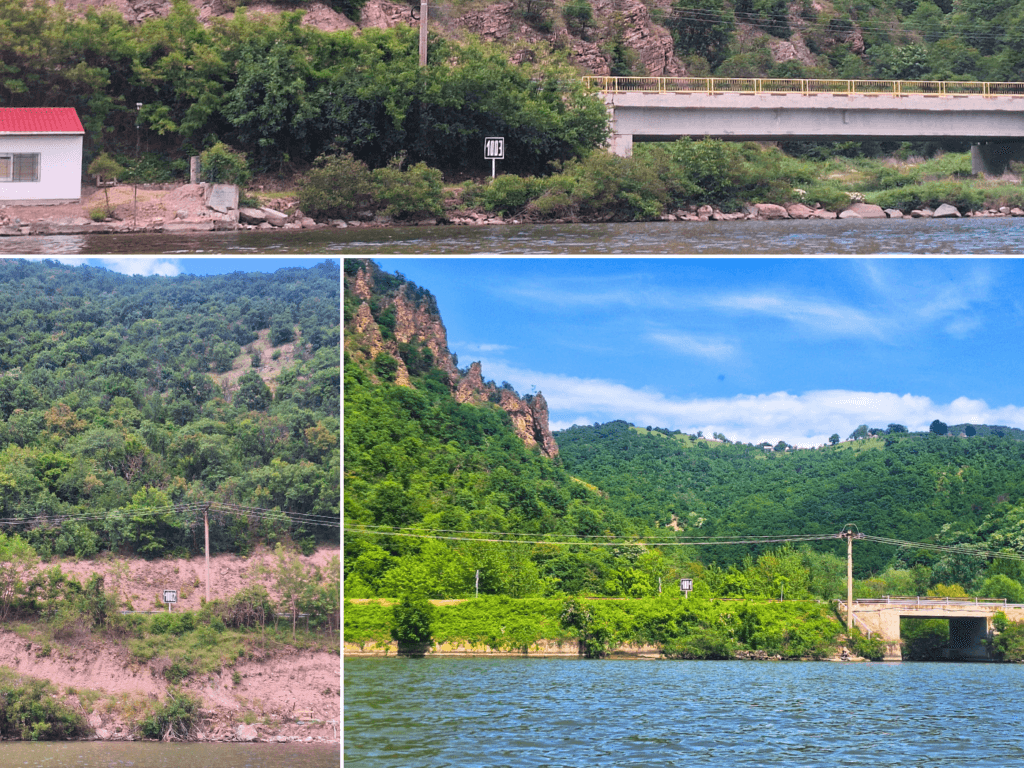

And also weird currents. But it was all wonderful and we managed to keep a straight line as the force of the water pulled us in deeper and deeper. We also saw our first kilometer signs in… weeks? They’ve been only on the left side of the Danube since probably Smederevo or even Belgrade. I really like them as an easy performance measure. But now they are on the Romanian shores and the first thing Jonas said is that he hates the font they chose.

Ahead of us was a large quarry that was the spawn point of the many dump trucks that we saw (and heard) pass Golubac Fortress to head inland. There’s supposedly also a waterfall called Beg Bunar, but we didn’t see any. Perhaps it’s dry after a few days without rain.

As the gorge narrowed, we passed a plaque on the Romanian side that memorialized the regulation works done on the Danube in 1896 to improve navigability. It mentioned I Ferencz Jozsef (Franz Joseph I of Austria). Rocks were removed from the riverbed to make it deeper and the currents more predictable.

We were now one hour into the kayak trip and we’d paddled about 6.5 kilometers. I informed Jonas of that and he was happy with the result. We kept paddling to Dobra and using our second hour – which is usually our best in terms of focus and speed – to make more distance.

I told Jonas my three conditions to decide whether we’d paddle only to Dobra or all the way to Donji Milanovac:

- We need to be in Dobra before noon

- The current still needs to be notable

- The wind needs to be either still or provide us with a tailwind

Jonas added that “It must feel silly to stop already”.

One other reason I’d love to paddle to Donji Milanovac instead of just Dobra is that some 10 kilometers before Donji Milanovac, we will pass the 1000-kilometer mark. From that point forward, it will be less than 1000 kilometers down the Danube to the Black Sea. The Iron Gate also marks the beginning of the end for the Middle Danube. When the Lower Danube begins after the last dam, we’re in the final major division of the river before the Danube Delta.

So you can see that I was very motivated to put in the work to paddle more than 50 kilometers today. I knew it would be tough, but I also knew it would give us a motivational boost after so many days of kayaking hardship on the river.

Soon after, we pass the Serbian village of Brnjica. There’s a bit of a port facility there and some barges, but no movement. In fact, we haven’t seen a single ship yet. Suspicious?

Right after Brnjica, we come across two parallel buoys that mark the channel where the shipping lane goes. But there’s something very wrong: there’s a red buoy on the right-hand side and a green buoy on the left. Either someone fucked this up, or ships need to make some kind of slalom maneuver here. Human error seems like the more plausible explanation.

At the hamlet of Velika Orlova with eight (very nice) houses, we are two hours in. We’ve done 7.2 kilometers since the last hour, for ease of measuring our speed. Things are going well.

A small black helicopter flew over the Serbian side of the Danube. Serbian border police? I don’t think it was a scenic flight, because they seemed in a hurry.

There were some curves in the river. Jonas looked at his map with the route this unknown person from the TID took. They landed in Čezava at a place called Adventure Hub Camp. They didn’t camp there overnight but probably stopped there to enjoy a beer. As of 2024, the campsite with a beach bar is either abandoned or not yet open for the season.

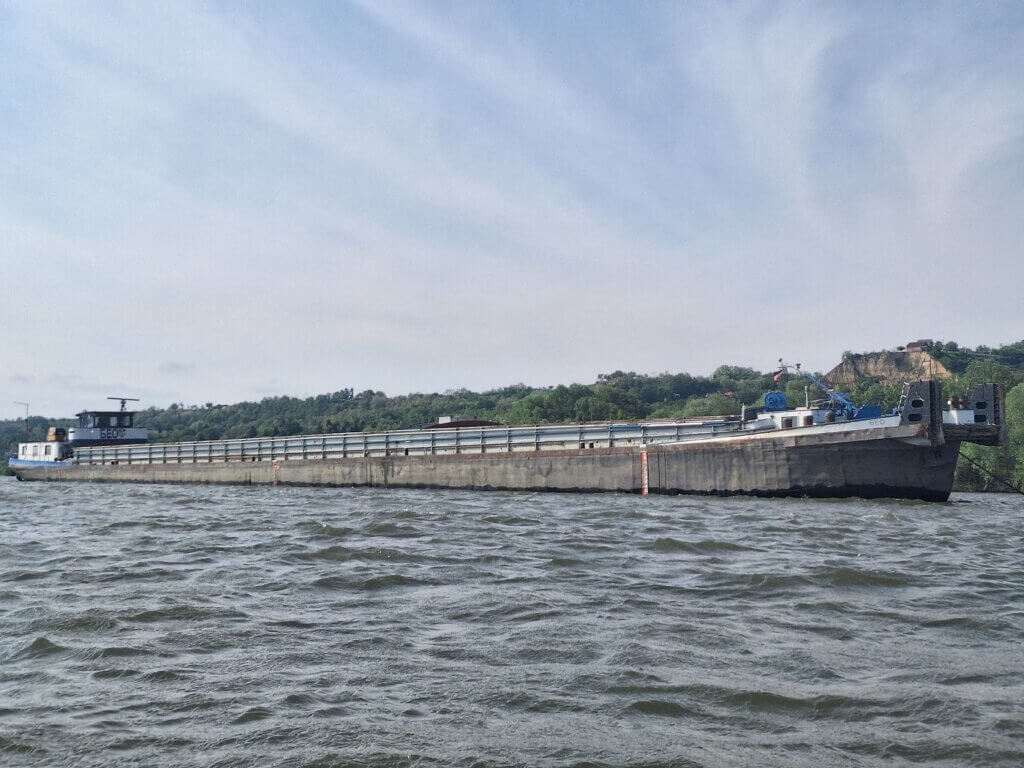

Another hour passes before we’re on the final approach to Dobra when a distinctive tailwind begins. After smashing a protein bar, I decide to deploy the kayak sail for the final stretch to our mandatory break spot. It’s strong and a lot of fun. Our first cargo ship of the day slowly pushes upstream.

We land near the football pitch in Dobra where a fisherman is sitting on the shore near a tractor. Usually, we’re not fond of people at our landing spot, but we need to land right now. It’s 11:12 when we land and I stumble my way up the embankment. Time to discuss whether we get out of the Danube here in Dobra or continue to Donji Milanovac.

Theory Will Only Take You So Far

All three conditions are met: we have a tailwind, there’s a current, and it’s before noon. And Jonas said it felt silly to stop now.

There is no excuse except our fear of not making it. I also offered to pay for the taxi back from Donji Milanovac or the hotel there in case we miss the bus that leaves at 17:30.

Our break on land was short but sweet. Sixteen minutes and we were out again. Jonas wanted to get cracking on the remaining 30+ kilometers. We’re not even halfway, but we feel optimistic about making it to Donji Milanovac. At the start of this year when I told Jonas we needed to paddle more kilometers in one day, he didn’t think over 50 was possible. There’s only one way to test out the theory that we can do it.

I deployed the kayak sail rather quickly while we made our way to the middle of the river. Next to the Romanian village of Berzasca, I searched for the sunscreen in my dry bag. It’s noon and time to reapply. Our course wasn’t very straight as the sail kept flopping, but we made 500 meters of progress without any paddling in a matter of minutes. Things were going quite fast. To our left above Romania, some ominous and pregnant clouds appear. I tried to take a panorama picture from Zucchini to capture the weather difference between Romania and Serbia.

Once we had both protected our skin once again, we sailed and kayaked. We were just getting into it when I spotted something through the blurry sail. I pulled down the sail and saw a small motorboat. We kept paddling, but the dark blurry spot got bigger and bigger instead of disappearing to the sides. I dropped the sail again. Jonas said this might be a police boat. Not Serbian—those are white. We put the sail up again and paddled in a predictable course until the boat was almost here. Then I dropped the sail and told Jonas to stop paddling to reduce our speed.

Two fellas on the boat were looking very closely at us. In the final seconds, I could ID their Romanian flag flying on the back of the boat. I said hello and waved and waited for them to speak. The guy not steering the boat asked where we were from.

“I’m from the Netherlands, he’s from Germany. Today we are kayaking from Golubac to Donji Milanovac. We are checked into Serbia. We are not landing in Romania. When we go to Romania, we will use the official border crossing.” I said in my loud-but-not-yelling voice while pointing backwards to the ferry crossing in Golubac.

The guy said okay and they left. Just like that. They heard a woman speak and listened and accepted what was said. I fully expected Jonas would have had to repeat everything I just said in his man-voice for the message to carry over, but this was a very pleasant surprise and interaction. May Romania soon become a full part of Schengen!

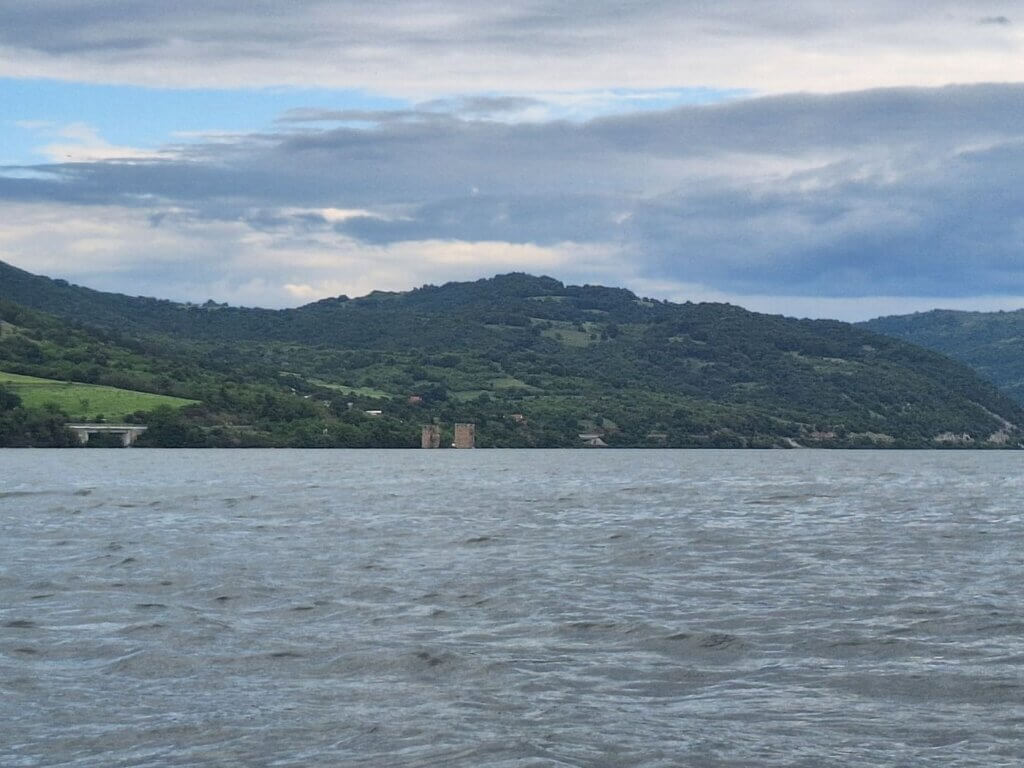

I don’t know what happened, but instead of returning to base, the guys just went on a patrol trip upstream on the Danube and disappeared from sight. We redeployed the sail. It wasn’t long until another blurry shape appeared in my kayak sail. It scared the shit out of me. Jonas laughed because he’d seen it for a while. They’re the half-drowned remains of Cetatea Drencova.

“A border fortress, it was built around 1419. Between the years 1429-1435 it was the property of the order of the Teutonic Knights, and from 1457 of the family of Iancu de Hunedoara. Being a border fortress, it was attacked several times and destroyed at one point by the Turks. Old documents refer to the dimensions of the walls of the fortress, which were between 20-25 m long, 15 m high, and 1.5 m thick. Today only 2 pieces of the wall can be seen, and they are not accessible because they are surrounded by the waters of the Danube.”

We paddled quite close to the fortress before entering the southward turn near the Romanian village of Cozla.

Tailwind Squalls, Jet Stream Speeds

Another serious narrowing of the canyon commenced, by the name of Gospogdin Vir Gorge. We encountered our second cargo ship of the day going upstream. The Serbian side of the canyon had a road going in and out of tunnels on repeat. The cliffs became tall and the clouds darkened.

Jonas had looked at the forecast in Dobra. It said it might rain soon, but also that when it rains it will be 0mm that falls. Wonderful.

The wind picked up and I deployed the kayak sail again. The winds were very strong and I couldn’t also simultaneously paddle anymore. It was Jonas’ job to set our course and paddle along while I tried to tame the sail. I unhooked it from my life jacket as it felt that with one strong gust, I could be launched forward.

I’ve never experienced such strong tailwinds in Zucchini. And I never got to take them to my full advantage before like this. The waves picked up from behind as well and we were properly surfing them at times.

When stable, I grabbed my phone to measure our speed. It was over 7km/h just going by the wind. At this point, any paddling Jonas put in didn’t even help us that much anymore. But it did help relieve my hands from the constant and powerful pull of the wind.

After so many days in 2024 with terrible and relentless headwinds, we seem to have finally chosen the perfect day. And this also proved my theory to Jonas that if there can be terrible headwinds, there can also be wonderful tailwinds. We just have to be free and flexible enough to choose our days.

At 13:30, we ate our second sweet snack, which was Vojvođanska štrudla sa orasima—a mini strudel with a sweetened walnut mix in it. The other variant with poppy seeds (sa makom) is more common. The walnut version is our favorite. Though we have a box of fried noodles we intend to eat on this kayak trip like we did in Rodrigues, it’s not that easy to eat while inside the boat.

To our left, a spectacular Romanian mountain appeared called Trescovăț with its bare cliff face. I asked Jonas if he needed to land somewhere now that we were a few more hours in, but he didn’t need to. Landing spots are very rare on the Serbian side of this area because of the huge amounts of scree at the waterline.

Jonas said that the unknown mapper from the TID made a stop in this area a few kilometers downstream at a museum and restaurant. I found it on my map and in the real world: Lepenski Vir. There’s this enormous white building in the distance that doesn’t seem to fit right in. It’s a prehistoric archaeological site of the Lepenski Vir culture that lived in this area between roughly 9500 and 5500 BC. Though their original site has been moved because of the Đerdap I dam, this site was also a place of early human astronomy in combination with that distinctive mountain Trescovăț across the river, forming a ‘double sunrise’ at some point in the year to mark a sort of calendar.

I was wondering how the TID people had enough time to land below the museum, visit the archaeological site, and then go eat at the main road a kilometer away. But then I remembered that the TID paddles only from Dobra to Donji Milanovac in one day. That’s only like 35 kilometers with good currents and perhaps even some tailwind if they were lucky.

1000 Kilometers to Go to the Black Sea

After this particularly cliffy section, the Danube widened a little once again. It’s after 14:00 and we are now parallel to the village of Boljetin. The bus back to Golubac also stops there, but it’s something like a 120-meter climb from the water level. With no actual path.

We paddled closer to the Romanian side through the turn and saw the signs counting down 1007 km, 1006 km… we’re almost there.

Though perhaps we promised the Romanian water policemen to not go to Romania, we are paddling close to the land here because of the upcoming 1000-kilometer sign. We’re not landing, as promised.

On the way there, we paddled past many riverside hotels, villas, holiday homes, A-frame cabins, and restaurants. Most of them are unmapped on my OSM map, though Google has a better idea of them.

1003, 1002, 1001…

The tailwind was gone and at times, it felt like it was sometimes even coming from the front. Paddling this close to the river also meant paddling through plants attached to the riverbed. They only started to appear in the Danube on the day we paddled from Smederevo to Ram. I wasn’t afraid of getting stuck in them, but it’s a bit nasty to have some plant material on one’s paddle unexpectedly.

We were scouring the edge for the 1000-kilometer sign. I hope it’s not surprisingly on the Serbian side, that would be quite a bummer.

Someone started playing music at their villa a few kilometers downstream. The music carried far over the river.

We found the 1000-kilometer sign tucked between bushes near a house on the Romanian shores. At first, I thought it was rather underwhelming and that if we’d paddle closer, it would probably disappear completely. But no, there was actually quite a nice spot to float for 10 minutes and take photos. Just trying to take a moment. It’s only 1000 more kilometers to go to the Black Sea! That means we’ve done well over 1500 kilometers—the exact number to be determined.

Edit: after arriving in Donji Milanovac, we’ve paddled 1708 kilometers on the Danube in 2019 and 2024. Just in 2024, we’ve done 454.7 kilometers.

We continued paddling towards the music on the left shore. Once we’re past that Romanian corner, we are parallel to what we call ‘The Hooky’. This cliff that sharply protrudes into the Danube is called Boljetinski Greben and it has a wonderful viewpoint of the Danube for hikers. It’s the end of the last The massive bight and widening of the Danube here also is the start of the Donji Milanovac Basin, which stretches between the Gospogdin Vir Gorge behind us and the famous Kazan Gorge. But the Kazan Gorge is for when we continue paddling after Donji Milanovac another time.

If you’re confused about the many widenings and narrowings of the Danube in this area, same! So, to recap, it’s like this: Đerdap Lake, Golubac Gorge, Ljupkov Basin (near Dobra), Gospogdin Vir Gorge, Donji Milanovac Basin, Kazan Gorge. And sometimes everything from Golubac to the Đerdap I dam is confusingly mapped as Iron Gate Lake / Đerdapsko Jezero / Lacului Porțile de Fier.

Anyway, go to this area of the world. It’s beautiful.

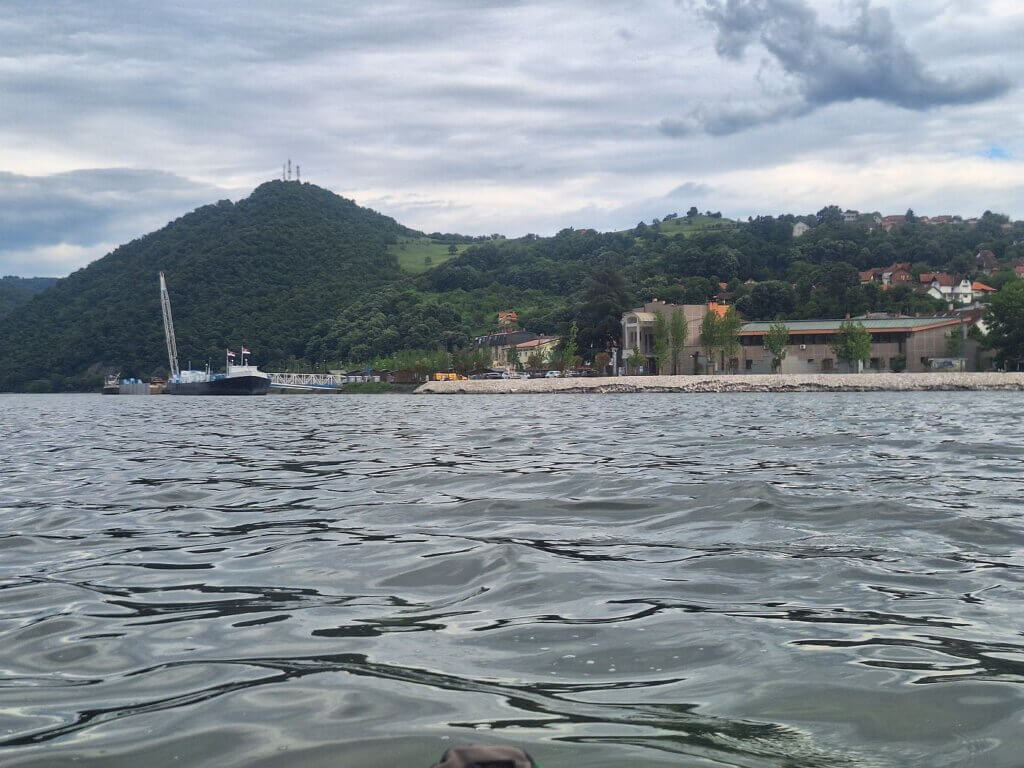

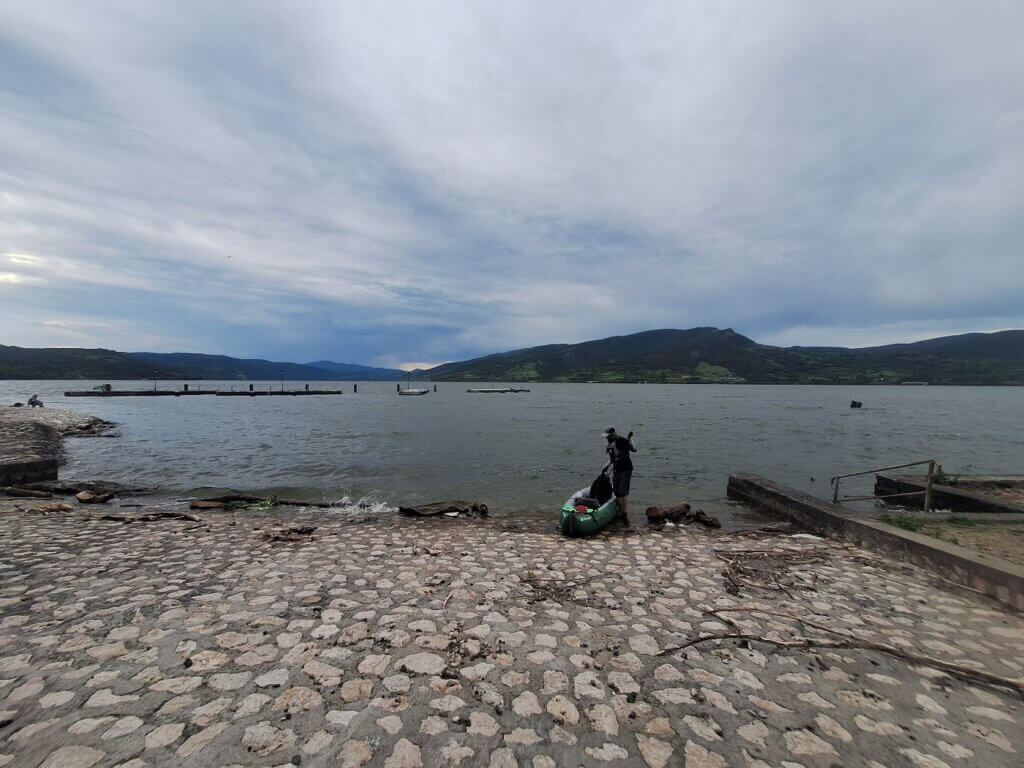

Arriving in Donji Milanovac

It was 15:15 when we paddled into the Donji Milanovac Basin while a cargo ship overtook us from the back. We kept paddling the curve to the left, mostly on the Romanian side. I hoped to go into the middle of the river at some point to catch some current and/or tailwind. But now, going to Donji Milanovac would be best by paddling in a straight line of about 10 kilometers.

We paddled past the 999 sign in front of the Romanian town called Svinița. It (allegedly) has a bus stop, in case we want to continue paddling the rest of the Danube from the Romanian side. Hopefully, we can figure out the buses in Romania as well as Jonas figured out the buses in Serbia. Behind us, we could see ‘The Hooky’ aka Boljetinski Greben well.

Svinița also has a Romanian river police port, but none of them came out to ask us what we were doing.

We were in the final stretch towards Donji Milanovac. We couldn’t see where we had to land from this far, but we aimed generally for the town. It’s still quite far to go. I was fairly sure we wouldn’t make the bus.

But then, by a miracle, the tailwind restarted. And she quickly grew strong. I could feel a sparkle of hope in the paddlers of the (one and only) deck of Zucchini. As we turned around the curve of the river, we could see that cargo ship again. That means we’re pretty fast once again.

With this optimism boost, it was time to take things seriously. We kept a focused paddle from 16:00 onward with few breaks. As we crossed the Danube to the right, I spotted the castle ruins of Cetatea Tricule on the left. We sailed across the river with a powerful wind, passing in front of a cargo ship traveling upstream. It wasn’t even a tight call. We were just that fast.

Now it was time to decide where to land. I used my draining battery to keep my map app constantly open with airplane mode for a straight line. I wanted to land at the stairs in Donji Milanovac town closest to what we thought was the bus station. It’s also at the Donji Milanovac border control, but I didn’t expect to meet any people there. Either way, if we would, then we could just tell them the same thing I told the Romanian police guys today, except Jonas can do it.

Upon arrival, I packed the sail up and saw that the lines in the water from the cruise/cargo ship mooring station were too low in the water. There was no way we could paddle under those easily in these winds and waves.

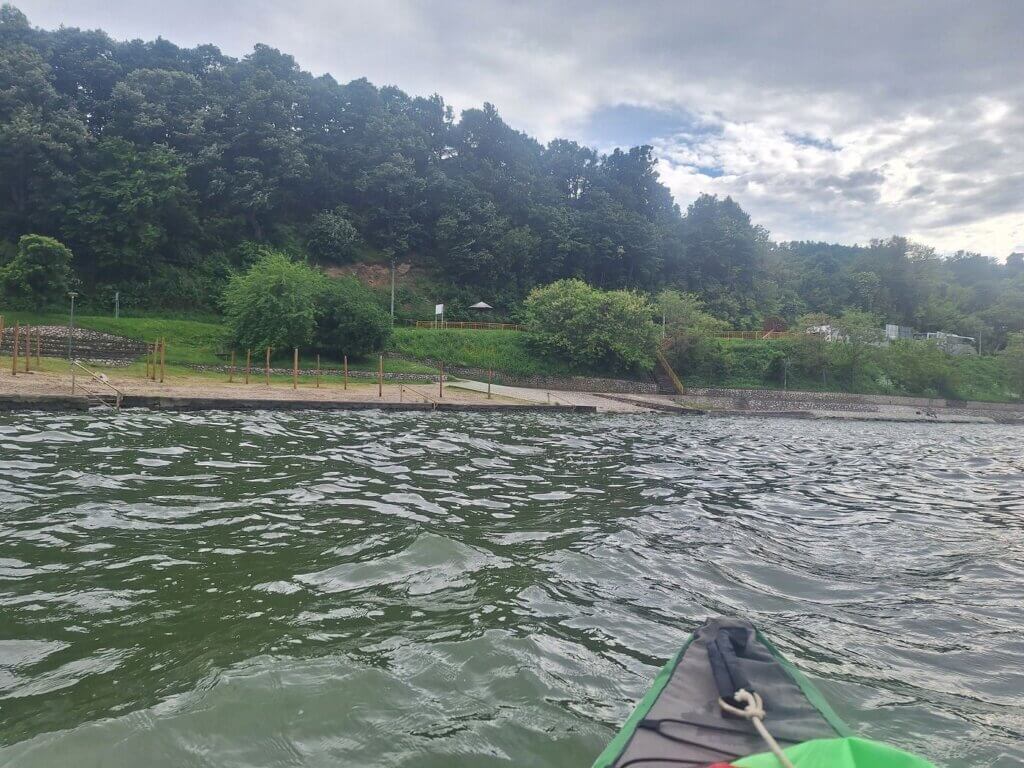

We aborted that mission and turned to Jonas’ preferred landing spot: the beach next to the marina. My initial dislike for this spot is that we will have to pack up Zucchini wet and having sand stick to her is pretty bad. But we had no choice now.

After turning, we paddled in a curved line toward the landing spot while the waves slammed against the artificial embankment, amplifying them. We dodged some fishermen and landed Zucchini at the non-sandy slipway at 16:56. We made it to Donji Milanovac! More than 50 kilometers!

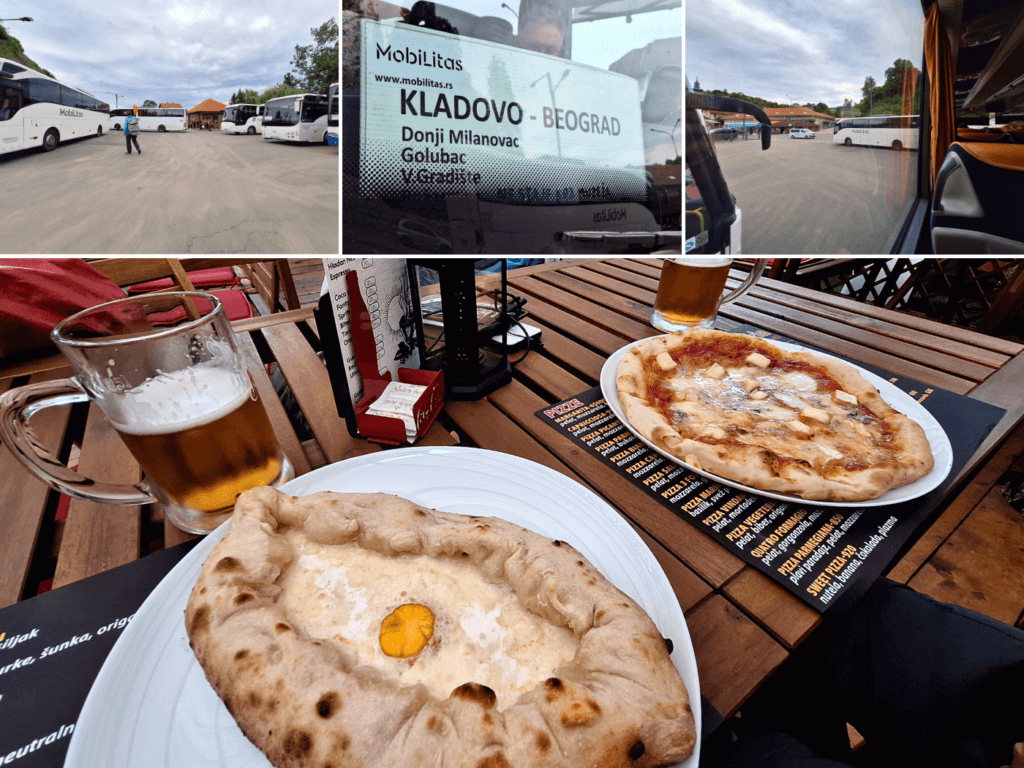

Miracles: Making the Bus from Donji Milanovac Back to Golubac

The bus leaves in about thirty minutes. Perhaps there’s a chance we will make it.

Don’t ask me how, but we poured the water out of Zucchini, dried off our feet, changed into land clothes, repacked all the loose stuff, and deflated and packed up Zucchini in 20 minutes flat. We’ve never been that fast.

We walked the 360 meters towards where our maps said there was a bus station in Donji Milanovac. The town was deserted. There was a youth hostel, but also a sign that said ‘closed’. Jonas asked a café owner – the first soul we encountered – there for the bus station. He said it was somewhere at the gas station and pointed in some convoluted direction. I was like shit, we will not make the bus now. And I really need to pee.

It was another 320 meters to the correct bus station, which is on the road passing through Donji Milanovac. Makes sense; the bus from Donji Milanovac back to Golubac is actually the bus from Kladovo to Belgrade. Why would it go inside the villages en route?

There were a lot of restaurants with potential toilets on the main road. The bus rolled into the station where there were many people waiting. There was no toilet at the small bus station. Jonas told me to drop the kayak backpack and go to a bathroom somewhere. I asked for some small cash just in case people are pissy.

Armed with 50 RSD and a full bladder, I headed into the restaurant across the bus station. I can also run quite fast if I have to. I asked for the toalet, dropped the money on the counter, and relieved myself. Always wash hands.

When I returned, Jonas was still outside the bus. He told me to stop running, no worries. He had already prepaid the two pieces of luggage at 50 RSD each. Some people from Donji Milanovac told us to board the bus before them. It didn’t make much of a difference, but it was very kind of them. The ticket is 850 RSD per person.

The journey back to Golubac was wonderful. We saw much of the river that we’d paddled today. And the inside of a lot of those Serbian tunnels. We had a wonderful time thinking, how the fuck did we paddle more than 50 kilometers and still made the bus?

Perhaps it’s not the point of this kayak trip to return to base at the end of the day. I would also much rather paddle from Golubac to Donji Milanovac with all our luggage and then stay there for a few nights. However, the Iron Gate area is a major paddling challenge. If we can choose the day we go out, why wouldn’t we? We are taking full advantage of Zucchini’s packability. It’s just not something you can do with a normal hard-shell kayak.

Also, this is an international border between two countries and an EU outer border. As seen with our interaction with the Romanian water police today. And now we are free to take the ferry from Usije in Serbia to Moldova Veche in Romania and be there legally. As seen by today’s paddling, it seems like there are plenty of towns and accommodations on the Romanian side of the Danube as well.

Back in Golubac, we walked from the bus station to our favorite restaurant called Wood Fire. We had a wonderful four-cheese pizza, a khachapuri, and some draught beers. We also met our favorite cat in Golubac next door at the Giros place. Once home, we unpacked a little and hung stuff to dry before taking turns showering. Tomorrow we will dry Zucchini in the sunshine.