If you came to this article from YouTube and just want to know the price to travel this route by riverboat, scroll down or elegantly click here.

The “downside” of traveling to a jungle city only reachable by riverboat, is that you know you’ll also have to leave it by riverboat! Our journey to and stay in Iquitos had been quite the experience.

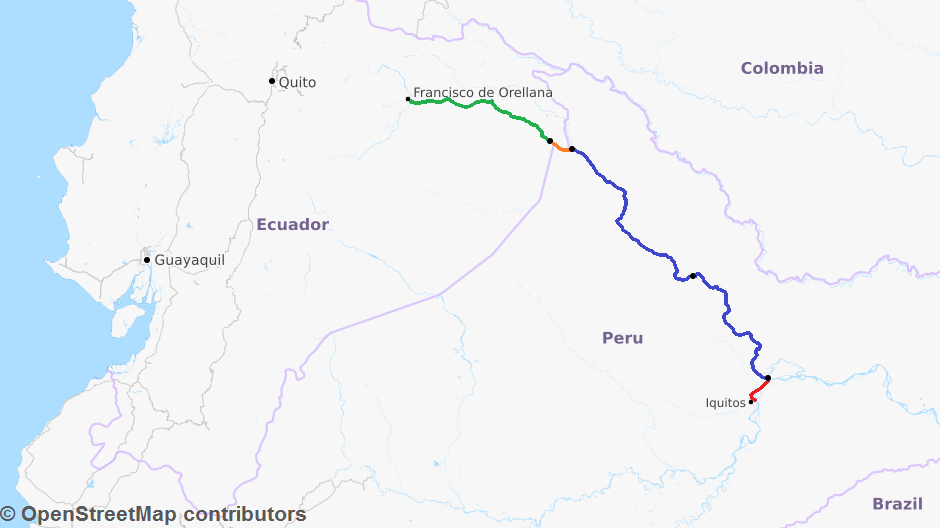

Last week I had to leave Perú. My 90 days stamp would expire on the 17th of May and I don’t like the idea of overstaying my welcome in a foreign country. I had spent about 10 days in the Peruvian capital of the jungle called Iquitos. From this city you can make three international choices for a border crossing:

- To Tabatinga, Brazil down the Amazon river

- To Leticia, Colombia, also down the Amazon river

- Or to Ecuador upstream on the Napo river

There are fancy and less fancy boats to all these places from Iquitos and a wealth of (mis)information. I wanted to go to Ecuador next. After this giant country called Perú where the distances are sometimes too large to hitch, a “tiny” country like Ecuador would be nice for a change. Before I left Lima, I encountered a blog post by Heather and John, who had taken the trip the opposite way from Ecuador to Perú. I was intrigued.

To clear the air from bullshit, I went to do something I rarely do: visiting the Tourist Information Office. The lady helping me said my request was uncommon, but not unheard of. Out she came with a bunch of papers, of which some were a schedule. I’ve never seen anything schedule-shaped in Perú in my entire three-month stay. The trip wasn’t going to be cheap, but I got myself into this situation now so I had to get myself out of there as well.

When I left on Monday the 15th of May, I decided it was time to keep a mini diary for this trip. Here are the snippets of wisdom, annoyance and other things I picked up by spending many, many hours on various boats. All while coughing my lungs out with a nasty cold.

Monday 15th of May: Iquitos to Mazan

This was going to be easy. Just go to one of the harbors, ask around for the boat to Mazan, get the fast one for 15 Peruvian Soles (US$4.60/€4.08). The boat trip over the Amazon river should only be 40 minutes. Then you need to take a mototaxi from the Amazon riverside to the Napo River.

That’s sort of where I got some weird questions since on my OSM map app I thought I had to first go to a town named Indiana and then take the mototaxi from there to Mazan. So what town name should I tell the ticket seller of the boat? My map showed me Indiana as the right choice.

At 10 in the morning, I showed up at the port where the Indiana/Mazan boats would leave from. The harbor is called “Puerto Productores” and it’s not the same harbor as the one I arrived in from Pucallpa. From the front, it just looks like a typical Peruvian market place: buzzing with people and produce. The minute I arrive at these places I get a little overwhelmed by all that’s going on. I walk up to a dude in uniform to ask if this is really Puerto Productores, and where the boats leave from. You can’t go around the market, you have to go through.

Behind the market are some dizzying wooden steps that take you down to the riverfront. I’m carrying a quarter of my body weight in stuff, so my main priority is keeping balance and not tripping over anything. Below is a floating market that’s also where the commuter boats moor. I find a boat that goes to Mazan and it only costs 8 Peruvian Soles (US$2.44/€2.17), but it would take two whole hours. I ask where the fast boat leaves from.

To get to the fast boats, I had to walk northwards on the wobbly wooden planks that create this floating town. It all looks very improvised, but it works mighty fine. Perhaps it feels a little bit like the set of a pirate movie. In the distance, I see a fast-looking boat. A few more planks to walk and I’m there.

The riverboat is empty. Traumatized by the boat (Eduardo) that brought me to Iquitos that just wouldn’t fill up and leave, I ask when they plan to leave. “When it’s full,” said the guy. He was eager to sell me a ticket. Alright, I don’t think I’m going to get a better answer. Let’s do it. Pretty much the moment I embarked, other people entered the boat as well. What was previously a relatively quiet area of the harbor, was now the main hub for vendors of ice cream, sunglasses and power banks to charge that smartphone. I pay my ticket and write down my destination as “Indiana” on the form. Within 25 minutes, the ship had reached its 26 person capacity and we left.

The ride was quite bumpy, which rocked nearly all passengers to sleep. The helmsman put the throttle at full speed and used it as an armrest. We arrived in the first town after the promised 40 minutes. Nearly everyone disembarked here. I asked where we were and a man told me we were in Mazan. Until now, I had been operating on the idea that Mazan was on the other side of the peninsula and I had to get to Indiana to take that mototaxi to the other side. I was told this was my stop.

Within seconds of leaving the boat, I was in a mototaxi racing over a tuk-tuk highway to the other Mazan. It cost 3 Peruvian Soles (US$0.92/€0.84) as promised on the schedule. Turns out there’s an Amazon side of Mazan and a Napo side of Mazan some 8 kilometers apart. Valuable intel!

When arriving in Mazan proper I caught my first glimpse of the Río Napo. That river is going to take me to Ecuador. How exciting! I found myself a hotel room for 20 Peruvian Soles (US$6.10/€5.43). Hotel “Leydy” was nothing fancy, but I could charge my batteries and rest before rising early to catch tomorrow’s boat.

It was still rather early, so I walked around town to hunt down both food and information about the other boat. After ending my raging hunger at the local market, I asked around for the boat at the Capitania. The uniformed individual wasn’t really in the mood for answering my questions right now. If I could come back later? Of course. Now he had inspired me to also take an afternoon nap.

Waking up I see some little lizards crawling over the window’s mosquito netting. After visiting the captaincy another time I have what I came for: confirmation that the boat leaves tomorrow at this harbor. It should arrive at 6 and leave at 9, but get yourself a seat before 7:30. On my way back to the hotel I witnessed a bold sunset over the river.

Tuesday 16th of May: Mazan to Santa Clotilde

No wake-up alarm needed. A faint image fell through the mosquito net before 6 o’clock. The silhouette of a lizard still on there. Perhaps it’s dead. I start coughing as if I have some catching up to do. The cool moist morning air is too much for me.

The near-daily routine of packing up my belongings happens on automatic pilot: smell the clothes, put on good clothes, roll up used clothes and put them in the vacuum bag, stuff clothing bag in the backpack, stuff other items in the backpack, brush teeth, put on shoes and backpack and go. I don’t even think about it anymore. Today, I take my time.

Around 7:30 I arrived at the boardwalk to the harbor. A spontaneous market had appeared. There are two new boats since last night. One long, one short. Both say “Trans-Vichu”, whatever that might mean. The short one only goes to Santa Clotilde, while the other one is the two-days boat that goes all the way to Pantoja, the border to Ecuador. 200 Peruvian Soles (US$61/€54.30) for the whole thing. Damn, but I knew this beforehand. The schedule I got from the Tourist Information Office in Iquitos has been spot-on so far.

This boat only leaves twice a week, every Tuesday and Friday. It’s known as the ‘fast boat’. The slow boat only goes twice per month. I need to take this boat, as it’s my only chance to stamp out before my 90-day stamp expires. The penalty for overstaying your welcome in Perú is only 4 Peruvian Soles per day – which isn’t the worst consequence – but I’d obviously prefer not to.

I’ve occupied a seat on yet another empty boat and decide to shortly head out to buy snacks for the ride. One guy is selling a Peruvian version of the Dutch new year’s snack oliebollen, but in mini form, and juanes. A juane is the Peruvian savory version of a surprise egg; wrapped up in two banana leaves you’ll find a ball of spiced-up, sticky rice, wrapped around a piece of chicken or fish and often an olive. It’s my favorite food from the Amazon. Best of all is that it only costs 1 Peruvian Sol.

Back on the boat, no one was trying to sell me things. My experience with taking boats in Perú has been that you never have to move to get your basic supplies. The vendors just walk on board to feed, clothe and entertain you. This boat was different, somehow. There were a bunch of young boys carrying things to the cargo area of the ship. They would later go up to the person who owns the cargo and get a few cents for their provided service. The stuff is heavy and the path to the back is narrow. One object that looks like the world’s heaviest fridge occupies the boat’s bow. No one moves it to the cargo area; it’s here to stay.

There are only 40 seats aboard and the average local is very middle class, judging from their shoes and the ability to pay for the fast boat. Some people seem to be engineers or technicians for mining, logging or oil rigging and the like. I wonder if their employer pays them to take this boat. I bet that for many taking the riverboat is just part of their weekly commute. For me, this is by far the most use of public transportation I’ve made on this entire continent. Call it my vacation from hitchhiking.

After 1.5 hours of waiting, a lady selling the oh-so-appealing-sounding gelatina (fruit jelly) makes her way on board and sells out in two minutes. It actually looked kind of good, I must admit. The boat leaves a few minutes after at 9:06 and I’m amazed by all the accuracy going on here. As a hitchhiker, I never deal with time schedules and any expectations for punctuality should peacefully be left behind in Holland, Germany and the like, before heading off to South America (or anywhere in the world). Everyone’s busy munching their gelatin breakfast. I nap.

I nap a lot on board. The riverboat is quite full (but not even close to Eduardo full) and some people had to swap seats to balance the boat better. Much like how they do it on a small airplane. Actually, I’m sitting on a former airplane seat. All the seats aboard are recycled from some other vehicle. I count three types: two kinds of airplane seats and one kind from a regular car. Some even recline! I’m more and more convinced that I’m not on a boat, but rather a low-flying airplane or amphibious vehicle.

Between and during naps I listen to music or map our route to predict when we’ll arrive in Santa Clotilde. The average speed is 25 km/h (15.5 mi/h). We make only a few stops. Sometimes we slow down for shallow waters or objects floating in our path. When it rains the two-person crew tries to close the door, but the fridge-like object prevents it from closing. It takes both guys and a little puzzling to make the cockpit rain-free. I hope the fridge needs to go to Santa Clotilde.

There’s another gringo on board. He naps continuously, barring that time we got lunch. Sandwiches. I got an omelet on a bun. A little bag of mayonnaise passes from the front to the back. One crew member hands me a plastic cup and a minute later the gaseosa arrives. I take some and pass it on to the next person. We all get two cups of Peruvian Fanta that day. Everyone seems to know the rules, but I wasn’t even aware there was going to be food included. Where the fuck did he get these tiny omelets from?

An hour before arriving in Santa Clotilde is the moment I really need to make a trip to the bathroom. I walk to the back of the boat trying not to mess with the balance. The toilet is tiny but incredibly clean. There’s even toilet paper! I’ve almost forgotten the challenge it was to visit the bathroom on the Eduardo just weeks before… Almost.

Upon arrival, the helmsman tells us to go to the ‘Princesa’, the hotel night that’s included in the price. Everyone gets a key from the hotel owner and finds their number. The electricity is not on yet, as it’s only 16:45 and still light outside. I drop my stuff and prep to go to town to find a pharmacy for my major headache. I find a small plaza with only other passengers from our boat. One oddity grabs my attention: a police mototaxi! As in, the backseat is actually caged like in a police car and there are flashy lights on top. I’ve seen enough now. I ask a local for directions to the pharmacy.

Santa Clotilde is a nice little town but at the same time the major healthcare hub in this part of Perú. An ambulance boat is parked at another pier not far from ours. I find the local Centro de Salud and ask the first person wearing doctor gear for the pharmacy. She tells me it doesn’t open until 19:00. Come back later. OK, so I just wander around town and rehydrate in the meantime.

The town is centered around its schools. There are many teenagers everywhere. Three kids walking past me greet me with a polite “Buenas tardes“, each of them. I reply in a similar fashion. Am I becoming senior and worthy of respect or are these kids just really fucking polite? I walk some more. It’s the same everywhere. People greet, but they’re not curious or pushy to make business. Just saying “Good afternoon” to everyone. One cheeky boy accompanied by two older girls says “Buenos días” instead, and all of them start laughing as if it was The Greatest Joke Ever. Not sure if utopian or dystopian, but I feel something.

The hotel room has a private bathroom. I take a cold shower by my flashlight in the darkness. Then the light turns on and all is good. Time to charge my things by the few hours of electricity and eat my evening juane outside on a bench. The faces from the boat become more and more familiar. This is the largest number of people I’ve seen smoking cigarettes together in Perú, again proving this boat isn’t for the abject poor.

I walk to the pharmacy at 19:00 and see it opened. I get one strip of 10 paracetamol for 0.50 Peruvian Soles and consider asking for more, but then I hear a lady who just queued behind me say something about malaria pills. Damn. I walk away and run into a foreigner in blue scrubs and matching eyes. Doctors Without Borders? Another health mission? We’ll never know.

It’s been decreed that the boat will leave at 4:00 in the morning. Be there at 3:30 is the advice. Someone had spread a departure time of 5:00 before. Why do I get the feeling this is going to backfire badly?

Wednesday 17th of May: Santa Clotilde to Pantoja

Somewhere it had to go wrong. Whereas the far majority of people managed to cut their night’s rest off at 3:15 to be back at the boat by 3:30 so we could all leave by 4:00 (or preferably earlier), not all got the memo. The reason for this early departure was that the distance between Mazan and Santa Clotilde is only one-third of the total distance to Pantoja. Today we had the largest chunk ahead and they were trying to arrive in Pantoja before darkness.

The boat seemed full to me, but we weren’t leaving. Someone had put a 20-liter container of some liquid at my leg space. The crew does a name check. All of us are presente except for two. At 4:10 I became irritated. Instead of a regular boat horn, someone had decided that installing a car alarm would be a great gadget on the boat. We sounded the boat’s car alarm a few times to no avail; villagers woke up, passengers stayed awake, but our final passengers wouldn’t show. We could have been told by the crew when leaving the boat the day before. Someone could have banged at all doors at 3:30 since we were all in the same hotel. This could all have been prevented.

Eventually, we leave at 4:42, a second after the last two passengers get on board and heavily apologize. “I thought we left at five,” one says. Yeah, we know. Most of us fall asleep while we head out into the darkness. Stars are still abundant in the dark skies. Upon completion of my first nap, the skies have turned pink again. I witness a beautiful sunrise on the Napo River. Tiny birds go about their morning business. Some get startled by our boat when we’re close to the shores. I feel aware of where I am, where I came from and where I’m going. My chest fills with that ardor that gets shit done.

After less than one hour we dock in some nameless town. One person disembarks. It makes you wonder why they couldn’t take another boat from Santa Clotilde the day before if the main benefit would be to sleep in one’s own bed. We make many little stops. Sometimes just deliveries of packages, most often a person leaves the boat with a human-sized sack of potatoes and whatnot. The fridge is still standing firmly on the bow of the boat. Irritatingly, in the path of everyone and everything. When people disembark from one side of the boat, other people have to move to reestablish balance, because of that heavy fucking fridge.

For breakfast we all receive a juane – oh joy! – and two rounds of lemony soda. I’m not sure if we’re all just eating out of boredom. In one hamlet we make a stop to pick up a new passenger instead of dropping someone off. An older, white woman joins our voyage. She’s wearing the pinkest outfit with the pinkest accessories and I don’t understand what my eyes are seeing. What’s her story? Is she the last missionary of the jungle? Is she sponsoring a kid from the hamlet to go to school? Does she simply live here? Is she terribly lost?

A few villages later, this same woman disembarks without needing to tell the crew her destination. Another white woman – a few years younger than our passenger – awaits on the shore the arrival of (presumably) her sister with a few locals. They hug warmly. Perhaps it was their lifelong dream to live out here in the jungle. Whatever it is, good on them.

There’s quite some traffic on the Napo today. Many canoes, both motorized and hand-paddled, make their way up or downstream. One canoe, in particular, stands out: one man, one woman, and a young child are going upstream. The man paddles in the front of the boat, while the woman is holding the heavy child and paddles at the same time. Obviously, neither task is going to be performed efficiently. What a metaphor for womanhood. Her deep and tired gaze catches mine. Our speedboat is about to make some waves in the direction of their canoe. What a metaphor for class struggles.

We stop at a dozen villages that are not on my map. There are fading ads from the last election for alcalde (mayor) of town. I don’t think anyone who starts their political career in a town this deep into the Loreto region of Perú is ever going to make it to Lima’s powerhouse. The boat is so empty now that I can take up one of the car seats and recline fully without messing with another person’s space. The floor is a little dirtier; empty soda bottles are rolling around and there’s some mud here and there. Someone left a juane under their seat and I decide to not let it go to waste and dive it.

My projections for our arrival time in Pantoja are that we’re not going to arrive before sunset. That means I’m probably not going to visit the immigration office today and stamp out of Perú before overstaying. There are intermittent rain storms that require the passengers to untie the boat’s tent-like rain protection, but also faint rainbows. We sound the car alarm every time we approach a town, to alert people of our presence.

At 16:30 the boat slows down. There’s no town here, but I do spot a hole in the foliage. Perhaps two trees are missing. Is this a path? Are we really going to stop here? One guy gets up to disembark, machete in hand. I was hoping badly that the fridge’s destination would be this easy-to-miss hole in the forest. That would be a spectacular plot twist to the fridge’s purpose. I am in awe nonetheless.

After 17:00 smoke appears on the shores in areas where the trees have been cleared to make room for villages. It’s dinner time in the jungle. Not for us though. There’s only one local passenger left; gringos form the majority now. The sun is reaching for the horizon and the boat slows down instead of speeding up for the last 20 kilometers before Pantoja. It’s already dark when I see the lights on the shore of what my map says is Pantoja. I get ready to disembark.

We made landfall by pushing other canoes sideways. In the darkness, I see three gringos in one canoe with three strings in the water between their canoe and our boat. They speak English and are annoyed. I ask them if they were fishing. They were, and now our boat has ruined it. They tell me they have already been waiting in Pantoja for three days already to catch the slow boat to Iquitos. I understand their pain.

There’s a cheap hotel in Pantoja where I drop my stuff. The other gringo from my boat tells me the immigration office has closed already. Shit, this means I’m officially overstaying Perú. I was so close! The gringo’s name is Alex and he’s from Minnesota. With a not-so-subtle air of arrogance, he lets me know he is “Always” traveling alone and finding himself through adventure, implying to point out the difference between him and me, a lowly tourist. I won’t bite. My judgment bounces back as quick as he fired his.

The arrival of the gringos at this border post has the consequence of attracting people in the business of transporting those to the other side. A local man in his forties introduces himself as an English-sounding “Peter” and tells us he has a boat he can use to bring us over the border to Nuevo Rocafuerte in Ecuador. US$20 (17,80€) per person, unless we can find more people to join in. This is still exactly what the schedule said, so I agree to it. The trip is supposed to take 1.5 hours when not making stops to see pink dolphins and monkeys. I ask if there’s a roof, but Peter answers me vaguely that there’s no sun protection, but there is rain protection. I’m 12 hours short to find out what that means exactly.

Back at the hotel, I see that the fridge has followed me all the way into the lobby, some fifteen fucking steps from my room. I question my own sanity. The only local who was on our boat all the way to Pantoja stands around. I ask him if he’s going to Ecuador as well, but he’s actually going up a side-river of the Napo: the Aguarico. It’s a smaller river that forms part of the border between Perú and Ecuador. I’m very much impressed. This guy’s journey still isn’t over! It seems like he’s the guardian of the heavy fridge. I know the thing is not a fridge – does Yamaha even make fridges? – so I decided to solve the mystery for once and for all.

The fridge is really an outboard motor for a boat exactly like the one I’ve just taken. Imported from Japan into Lima’s port of Callao, it made its way to Iquitos and beyond. This is where we part ways, finally.

Thursday 18th of May: Pantoja to Nuevo Rocafuerte

We had collectively agreed on an 8:00 departure time with Peter. At 7:00 I first went to get breakfast. We were told that the immigration office would open at an ambitious 7:30, so we would be stamped out of Perú and ready to cross the border half an hour later. I walked out of the hotel with just my passport and rain jacket, as there was some downpour just minutes before.

Alex had pointed out a little home restaurant the night before that “only prepares eggs”, as if that’s a bad thing… If someone is willing to scramble me some eggs, I get super stoked. For 5 Peruvian Soles (US$1.52/€1.36) I had a great Last Breakfast in Perú: scrambled eggs with onion and sliced fried banana all done perfectly, with complimentary cinnamon tea. I was ready to deal with some bureaucrats.

A short walk up the hill you’ll find Pantoja’s immigration office, next to a police station and an army base. I arrived at 7:45 and found an irked Alex. The office hadn’t opened yet and he was waiting there for an hour or so. I get into a proactive mode and find a human being in the police station. He tells me to “knock hard” on that door. It seems very telling to how business is conducted at this outpost. I follow the advice and even put in a desperate-sounding “Holaaa!” for good measure. A tiny dog with its paralyzed tongue hanging out sideways felt called.

A few minutes later, there’s some activity behind the locked door. A young man, barely awake and dressed, sticks out his head and asks if we can come back at 9:00. The satellite internet connection has been lost and he can’t put our details into the database at this moment. I tell him we’re not stamping into Perú, but stamping out, and that we have a boat to catch now. We hand over our passports and he disappears for 20 minutes. Occasionally we hear a brief thump: the hopeful sound of a stamp hitting the paper.

When the officer comes out again he’s also dressed. Alex gets his passport back, but I have to come in and pay the multa (fine) for overstaying, as expected. I fill in a form that says not much but quotes the number of days I’ve overstayed (just one) and the fine I have to pay for having done so (4.10 Peruvian Soles (US$1.25/€1.12)). The sweet sound of getting that exit stamp set me free to go to Ecuador.

I picked up my stuff from the hotel and found Alex and Peter waiting at the latter’s synthetic dingy. We set out with our backpacks on a blue sheet of plastic to prevent them from getting dirty and wet from the bottom. Peter tried catching the attention of the military base, as the last permission to navigate these waters, but no one was there either. Twenty minutes into the trip we stop at some trees with tiny monkeys in them swinging, jumping, and being total dicks to each other. It’s nice, but the skies are overcast and I see an angry cloud.

Five minutes later the rain starts. Peter puts the backpacks off the dinghy’s floor and wraps the blue plastic sheet around them to prevent them from getting rained on. I get another blue plastic sheet and Alex gets nothing but a cool story in the end. What is at first a pleasant drizzle becomes heavy drops of rain rather soon. I hide my guitar bag that carries my little camera under the blue sheet and put my body under it too. The sun cream I had optimistically put on my face starts dripping into my eyes causing a nasty sting.

By now, Peter is wearing a poncho like the pro he is and motoring while standing. I keep thinking it’s not the worst rain I’ve been in, until seconds after I had this thought it actually becomes the worst rain I’ve been in. The boat catches about a liter of water per second. The water stands so high now in the boat, that it enters my otherwise rather waterproof hiking boots from the top. Peter is worried, so he starts scooping water out of the boat with an old, cut-open container. There’s only one, so it swaps hands from Peter to me, to Alex and back. I scoop to the best of my ability with only my guitar now under the blue sheet. I’m soaking wet head to toe. My clothes get heavy. After scooping I get back under the plastic sheet.

Then we hit a fucking sandbank in the middle of the river. We get grounded pretty badly. I’m under my sheet or scooping while Peter walks out of the boat onto the shallow sand to push the boat out. It takes about 10 minutes to free us before we’re going again at full speed to Nuevo Rocafuerte. I ask Peter how much longer, and his response is “30 minutes”. At least that sounded honest.

When we arrive, the rain has slowed down, but not come to a full stop. The first sign I see on the Ecuadorian shores reads “Oil is good for the community”. Instead of letting us disembark at the nice dock with stairs, Peter decided that after this shit we could also climb up a muddy hill – for which I required help to ascend. Soaking wet, slightly muddy and probably having my camera and other items destroyed, I hand Peter the 60 Peruvian Soles for the ride. He goes back into his boat. Alex goes to the immigration office. I go to the nearest accommodation.

Ecuador replaced its national currency the Sucre in the year 2000 and adopted the US Dollar due to the ridiculous inflation of the former. I knew this beforehand, so I made sure I had a base stash of dollars. Hostal Chimborazo charges US$10 for the room per night, which is quite a steep increase from Perú. The room is nice though, and there’s even WiFi! My first order of business is taking off my wet clothes, drying myself with a towel, putting on dry clothes and squeezing the water out of the wet ones and my shoes over the hostel’s balcony. I take the batteries out of my tech, dry stuff with toilet paper and notice not everything seems completely ruined. I fall asleep.

After a few hours, I wake up coughing and realize I still have to go to the immigration office to stamp into Ecuador. It seems to have stopped raining, but it’s not like the threat of rain has gone. I ask where the immigration office is and get pointed six blocks down a street. There’s not a single mototaxi asking for my business. On my hike in flipflops, I walk past a brand new college promoting careers.

One room of the police station has a paper saying “migraciones“. It’s empty. I find a person to tell me which door to knock on and eventually a guy – again, barely dressed – comes out of a dormitory with a key to the office for immigration business. He assumes I’m leaving Ecuador and going to Perú, and he’s a little surprised when I ask him for an entry stamp. At the desk in the office, he analyzes my passport while breathing heavily. Nothing is happening for a full five minutes: he just stares at the first page of my passport. Kind of creepy.

“¿Cuál es su país?” he asks out of nowhere. “Holanda” I respond, or “El Reino de los Países Bajos“, which only caused unnecessary confusion. The guy opens his smartphone and starts taking pictures of the first page of my passport. I’m not sure if this is for personal or official use. I catch a glimpse of his screen and see that he has WhatsApp open and that he’s forwarding the pictures to someone on the other side. Then he walks outside with my passport to take pictures in natural daylight. He comes back in, still dissatisfied with the results. At the desk, he pages through my passport to find the Peruvian exit stamp.

This whole dance of finding a page, taking photos inside and outside, with flash and without flash, applying the rule of thirds and not, goes on for another thirty minutes before he speaks to me again. The guy explains that the official network is down, that’s why he has to WhatsApp it to a colleague who can put it in the electronic system. I got that. He enters my details into a record-keeping book – takes photos of it – and stamps my passport with the entry stamp. Finally! He is about to hand it back over to me, but then swiftly changes his mind and takes my passport for another round of photos, so his entry stamp is well-documented, too.

Enough bureaucracy for today: I scroll the internet and go to bed early. I’ll never see Alex again.

Friday 19th of May: Nuevo Rocafuerte

With my fresh 90 days for Ecuador, I am now officially not in a hurry anymore. I decide to stay another night in Hostal Chimborazo, mainly to give my tech a higher chance of survival. After a US$3 breakfast, the owner of the hostel walks up to me and tells me I can get free medicine at the Centro de Salud for my cough. I guess someone didn’t sleep well because of my incessant coughing – though I didn’t either because of someone’s incessant snoring. I take up his advice and go for a walk.

The sun is powerful when the clouds are gone. It’s a short hike to the clinic. The building is all on one floor, but it occupies a very large area. Medical information plastered on the walls. What are the symptoms of dengue, malaria and other diseases? A machine supplying free condoms. A poster explaining your rights as a patient: to know the name of your doctor, to receive a second opinion, and so on. I realized for the first time that there are some things going on in Nuevo Rocafuerte, and perhaps Ecuador as a whole, that are… suspiciously advanced.

At the clinic I should have waited in line to be served, to then get a consult and to perhaps receive antitussive medicine against my terrible tos, for free or not, but I decided against that. I didn’t want my first act across the border to be using the medical system, at the expense of others or not. It all just felt kind of odd. I guess my main goal, in the end, was to satisfy my curiosity about what healthcare looks like in a small jungle village in Ecuador.

The rest of the day was filled with drying items from my backpack, getting involved in pointless internet discussions and watching my clothes dry. This powerful sunshine didn’t last long; soon the heavy rain rolled in like the day before. I watched the rain from the balcony. In between dry spells, I would try to get information about when the boat to El Coca leaves. It would leave at 5:00 and costs US$18.75, which is an odd price and also more than the US$15 it said on the schedule that didn’t survive the rain. People talked about the Saturday boat as if it held some special powers.

I just wanted to know if it was both rain and sun proof.

Saturday 20th of May: Nuevo Rocafuerte to El Coca

Finally, the last riverboat of my journey! Packed and ready by 4:30, there was no boat activity around the dock until 5:00. A small group of individuals waited around the dock in the darkness. I observed the activity from my balcony. There’s a couple with matching Deuter backpacks sitting on the sidewalk. A boat arrives and things get serious. I go downstairs, but it turns out this boat was a false alarm. At some point, some men in uniform arrived. He asks us gringos for our passports and checks if we have a stamp. Scribbles shit down on a form. Hands passport back over. The couple is French.

At 5:30 the group climbs into a boat that leaves within an efficient fifteen minutes. There’s no seats facing the direction we’re going, just a large, comfy bench at the sides. There’s enough space for half of us to lie flat and stretch full-length. No one tried to get the boat to maximum capacity. This is a novel development.

I continue sleeping until we stop in a town with a more serious military presence. A man in a wheelchair gets lifted into the boat by uniformed men. Six other people check the passenger’s national IDs, but only one of them is qualified to check the gringos. I hand over my passport and answer questions like what’s my profession (student), what’s my purpose for visiting (tourism), how long will I stay (1.5 months), how I’m leaving the country (to Colombia) and how did I enter (from Perú). He writes down my answers and checks my entry stamp again for signs of malice.

The drowned schedule said the trip from Nuevo Rocafuerte to El Coca would take 12 – 14 hours, which meant we would not arrive before sunset. It also said we would make a lunch stop at a town called Pañacocha. To much of my surprise, we made our “lunch” stop at 9:40 in what was definitely Pañacocha. We disembarked to get food, go to the bathroom and drink something. It was not included in the price and I wondered if Ecuador was really going to be this much more expensive than Perú or if it’s still not a conclusion I can draw from the little data I have.

We were going much faster than projected by Perú’s schedule. The boat was going an average speed of 30 km/h (18.6 mi/h) and the river didn’t meander much. I made some calculations of my own and saw that we would be in El Coca at 15:00 perhaps. After our lunch break, a crew member collected the cash and wrote the tickets. US$18.75 indeed. Some of the change is odd coins that aren’t really US Dollars, but sort of Ecuadorian quarters, dimes and nickels that hold the same value.

This boat trip is rather uneventful. There are no engine problems, we don’t run aground, it rains but we have cover, we’re ahead of schedule. At 13:40 I see a suspension bridge up ahead. That’s El Coca, also known as Puerto Francisco de Orellana. That place has ATMs and a stable internet connection. There I can go to a supermarket and get my own food. That’s where I can do my laundry.

This is where I can finally hitchhike again.

Liked This Epic Post? Share It or Pin Me Please! 😀

How Much Does It Cost to Travel by Riverboat?

Note: the prices in Euros (€) are just for reference for my euro-thinking readers. You can’t actually pay these boats in Euros, it’s not a good back-up currency in South America.

Iquitos to Mazan: 15 Peruvian Soles / US$4.60 / €4.08 Every day until 15:00

Mazan – Santa Clotilde – Pantoja: 200 Peruvian Soles / US$61 / €54.30 Twice per week

Pantoja – Nuevo Rocafuerte: 60 Peruvian Soles / US$20 / €17.85 – Every day

Nuevo Rocafuerte – El Coca: US$18.75 / €16.74 Every day

The total amount for taking the boats will be US$104.35 / €92.97, of which the majority will need to be paid in Peruvian Soles.

Money: It’s best to carry around 350 Peruvian Soles for the boats, the food you might buy and the occasional accommodation – whether you’re coming from Perú or going there. You’ll need about US$80 for the Ecuadorian leg of the trip, but it’s never a bad idea to carry more dollars. There’s not a single ATM once you leave Iquitos or El Coca.

The quickest time you can accomplish this? It’s technically possible to leave Iquitos the same day the Mazan boat leaves. That would be Iquitos – Mazan – Santa Clotilde in one day . On day two you do Santa Clotilde to Pantoja. Day three you stamp out of Perú and take a dinghy to Nuevo Rocafuerte where you stamp into Ecuador and sleep a night because the boat to El Coca already left. On the last day you take the boat to El Coca at 5:00 and arrive in the afternoon or evening. The minimum in this direction is 4 days.

If you’re traveling downriver from El Coca to Iquitos, you might be able to do it quicker. Time your departure to catch the fast boats beforehand. Do El Coca – Nuevo Rocafuerte – Pantoja in one day . The next day you take the fast boat from Pantoja to Santa Clotilde. The third day you continue to Mazan and upon arrival in Mazan, you might be able to take a mototaxi across the peninsula to the Amazon side and catch a late boat to Iquitos. This would be a minimum of 3 days.

So Why Didn’t I Hitchhike the Boats?

Boat hitchhiking takes time. Lots of time.

Besides having the time, it also requires a couple of other conditions to be met:

- Are there many private boat owners?

- Who is in control of the passengers?

- Do the boats go far?

- Can I clearly communicate what I’m trying to accomplish and why?

- Do I need to go somewhere specific or do I not care about where I end up?

- Will people accept me as an adventurous person or will they see me as an exploitative tourist?

You can imagine that many of these questions can’t be answered favorably in this part of the world.

My main priority was visiting the jungle in Perú and reaching a hard-to-reach destination over land and water. I like the challenge. Three months to stay is incredibly short for a country as vast and geographically challenging as Perú. I don’t want to overstay, as that just seems like a big middle finger to the country that kindly hosted me for the last months. Call it my holiday from hitchhiking 😉

Thanks a lot for this detailed post! It sounds doable to do it the other way around. I hope the scenery was also worth it besides the occasional monkey.

Hey Michiel 🙂 You’re welcome! I think it’s very doable in any direction, but down river is always easier than up river I think. Let me know if you’ll do it yourself and how you experienced the trip. I hope you’ll see a few pink dolphins!

Hey,

Thank you for this awesome post. I am planning to do this trip from Iquitos as well. Two concerns I have: I will be traveling with not only a big 70L.backpskc but also a bicycle. Will there be a problem taking my bicycle on this boat journey?

Secondly, I have a flight out of Quito, Ecuador, so of the boat journey is inconsistent or often delayed, I could.miss my flight. Do you know how reliable it is to do this boat journey and make it to Coca within 7 days? I will einitrly give myself a couple extra days just in case, but if it’s a really unreliable journey, then I don’t know if it’s worth risking missing my flight.

Also, is it easy to get from Coca to Quito?

Thanks!

Danny

Thanks Danny! 🙂 They transported a giant box with outboard motors, so your bicycle won’t be a problem at all. All four boats were big enough. You’ll probably just get some weird stares from people or comments about gringos and their bikes 😉 I had a schedule with me after consulting the Tourist Information in Iquitos and it was spot-on the entire way. No delays, no technical issues, no excuses. If you don’t miss the second boat (Mazan to Cabo Pantoja) you’ll arrive just fine, so make sure to catch that one and you won’t have any troubles. Last time it checked it left on both Tuesdays and Fridays really early, so arrive the day before. Getting from Coca to Quito is also really easy, but I hitchhiked and I assume you’re cycling, so I can’t really advise you on that.. besides that you’ll have to go up the Andes to 2300 meters, which you’re probably aware of.. so.. good luck and bon voyage! 😀

Hi I know this is probably a very naive question but did you feel safe travelling this route alone? How good is your Spanish?

I have a 55L pack and some time and would really like to travel via boat but as a solo woman traveler I’m not convinced it’s a great idea. I speak rudimentary Spanish (enough to get by) but not good enough to feel like I could understand everything said to me in small villages where people don’t speak any English.

Thanks! And great post!

Hi Rae, not sure if this message comes in time for you, but I did feel safe traveling this route. My Spanish is pretty good, but I didn’t particularly need it that much on this route. If you just know what is the next step after each boat, you’ll be fine. Local people here don’t necessarily speak Spanish as a first language either, and those you depend on know how to deal with visitors. I’m sure you’ll encounter other foreign travelers as well, so tell them you’re traveling alone and would like some help with Spanish every now and then.

Happy travels in Perú and Ecuador! 😀

Hi there!! Your article is so awesome and helpfull coz I was looking how to get from El Coca to Iquitos by boat as well. Do you know or did you meet some people that carried bycicles on boat if was possible?

Hey Emanuele! Thanks so much 🙂 I think it’s possible to take a bike on the boats as I’ve heard stories of that before. They managed to take a some super heavy boat engines on the front deck, so a bike should definitely be possible with a little negotiation maybe about the price. Every step of the way, people were transporting huge items, so it’s just a matter of finding the right person with the right boat. Happy travels and good luck cycling around South America! 😀

Thanks again for this really helpful post. I completed the journey from Iquitos to Ecuador back in September and had no problem. Everything went smoothly, on schedule, and I was able to easily take my bicycle (and bike bags) on all of the boats. One of them tried to charge me extra for bringing the bicycle on but I negotiated the price down to something really minimal (or maybe even free, I can’t remember now).

Thanks for getting back to me Daniel. This is really good information for other cyclists crossing the rainforest 🙂 I hope your journey continues!

Very informative. Just what I needed to know. I’m about 70% sure this is what I’ll do in October, coming from Manaus… a few days in Iquitos, and then on to Ecuador. No clue where exactly, but I’ll figure that out later. My main interest is getting great photography. So I’ll go where the shots take me.

I think it’s a great place for photography and I’m sure the pictures will be awesome! Don’t forget to bring some waterproof bags to protect your camera gear. Would be sad to lose those photos.

how would it be getting a boat from Coca and getting dropped off on the river bank? around 30 to 35 km east?

River bank as in middle of nowhere, without any civilization nearby? Might be tough but if there’s a safe place to stop a boat, it must be possible. You might need to take two boats, like one bigger boat and then one tinier, more local boat. I’m quite curious about your plans now 😀

ahhhhhh one day i will dissappear somewhere i hope. live off the land in peace at last.

can you tell me if there are boat taxis in coca that i can hire to drop me off along the river?

In principle you can get out at any stop you like with the boat taxi I took. If you have a destination that is not a common stop, I’m sure you can tell the captain you want to be dropped elsewhere – as long as it has a pier to dock at! Maybe you’ll get some weird looks or be discouraged from doing this, but I’m sure you can negotiate your way to get where you want to be.

it appears to just be a beach on the map.

Thank you so much for this.

Me and my girlfriend Will try this trip in a few days from now.

And all off this information is just What we needet.

Ill let you know how it went;)

Enjoy the journey! 😀 Looking forward to hear your experience!

Fantastic narrative–love it. I am planning to do the same in reverse but with a motorcycle and would appreciate any further advice.

Best regards.

Mo

Happy travels with your motorbike! Let me know how it went 🙂

I read the title and the first chapter of the article and realized “YESS it’s possible”.

Following your advice I went to the tourist info in Iquitos (iPeru at plaza de arma) and started the journey. I downloaded this page to read everything later and during the trip I did so. While reading it felt like you were sitting next to me as totally similar things happened (e.g the little kids in Santa Clotilde saying buenas dias instead of tardes).

What I can add is that the whole journey is possible in 3 days. I did it this way:

Day1: Iquitos-Mazan-Santa Clotilde

Day2: Santa Clotilde – Cabo Pantoja – Nueva Rocaforte

Day3: Nueva Rocaforte – El Coca – Bus to Quito

It was possible, because as I was able to get the stamp after 6pm, as the guy of the immigration office lives in the same building and was friendly enough to open the office again. After a guy drove me and some others to Nueva Rocaforte where we slept on the street as all of the 3 hostels didn’t have any free rooms or wanted to charge 25 dollars. The next day at 6am the boat left to El Coca. The same day I took a bus to Quito.

Crossing the border from Cabo Pantoja to Nueva Rocaforte at night can be dangerous, as the river carried a lot of trees which the driver can’t see (or sandbanks :-)) so just go if it’s a bright night and the moon is shining.

Thanks for sharing your experience. That’s great advice!

Thank you!! I hope I can made it too!

In which building or hotel were you staying?

There is a Sunday option as well nowadays 🙂

Thank you very much for the detailed information!!

I have a little more time.. where do you recommend to stay longer? Iquitos? Coca? Or somewhere in the middle? I’m looking for a basic and real Amazone experience!

And, there is an ATM in Iquitos I understand. How do you get the Colombian dollars on the way?

Thanks again!

Hey Ilona! Nice that you’re starting in Leticia, Colombia. 🙂 I didn’t visit Leticia. I’m not sure how you’re getting to Leticia, but I guess if you don’t yet have Colombian Pesos you came from Brazil. Leticia has ATMs. It’s always good to still have some US Dollars on you in case ATMs aren’t working or if you just crossed a border.

If you’re looking to stay longer in a place with amenities, both Iquitos and El Coca are fine. Iquitos is more ‘jungly’ than El Coca and offers quite some rainforest tours and activities. From Iquitos you can also try to travel overland to Nauta if that’s of interest. If you’re looking for less infrastructure and more vibe, you can stay an extra day or two in Cabo Pantoja or Nuevo Rocafuerte. Nuevo Rocafuerte has internet and such things, so it’s also not completely off-the-map.

Hello!

Thank you for all the information!! It definitely helps me a lot!!

I have a bit more time, where do you recommend to stay a few days? To get a real feeling of the Amazon? Somewhere along the way? Iquitos? Or Ecuador? I will probably start in Leticia.

I did. that from Iquitos to coca. But individual may with a small crew and took like 2 weeks in 2008. 😊

Hi Chris. Wow, that must have been quite an adventure.

Hello ! I want to ask a few questions as I am planning to go to the Amazon as well ! I don’t know where to begin actually ! Oh well I Am 25 years old I haven’t travelled outside Europe before but I am thrilled with Amazon and Perú . I actually want to combine these two trips but I don’t know how … I have searched for tours and I think that it’s a waste of money and that it’s very touristy … Also very fancy for me ..

according to Amazon , I want to stay with an Amazon tribe in Ecuador ..but I can’t find something .. I have watched several YouTube videos from people who stayed with tribes and I really want to stay and experience their culture . Of course that is challenging without a tour guide . but I don’t want to be a part of a group .

I am also a bit concerned about Lima and safety issues there . I’m a girl , 1,60 cm not that strong . Of course I can kick but I don’t know what will happen .. What do you advise me about the money ? Should I have my card ? Should I have some cash with on me ? Also in Perú , is it worth it to go to Machu Picchu ? I mean the whole trip was about Vini Cunca (rainbow mountain) and then I said okay why not machu piccu .. okay I know too many questions….love from greece

Thanks in advance

Hi!

I found out that there are speedboats now directly from iquitos to pantoja which are promoted to arrive at lunch time in pantoja, rather than only from mazan. That way ideally you might be able to safe one day – if the boat is in pantoja before the migration closes. Currently they go tuesday and saturday, this tour company offered it to me for 290 Soles +51978023463 (another one offered it for 300, let’s see if I can save another 20 soles or so with negotiating lol)

Hey Moritz! That’s great to know. So this speed boat doesn’t make an overnight stop in Santa Clotilde? I hope you had a wonderful trip to Perú!