These events happened on October 3rd, 2021. Our Booking host in Heniches’k named Yuri offered to do a day trip with us down the Arabat Spit to visit some hot springs and a pink lake. This eventually turned into a little adventure with even more spontaneous stops and detours along the way. The Arabat Spit is geographically part of the Crimean Peninsula, but administratively it’s Kherson Oblast. Russia didn’t annex this part of Crimea back in 2014.

Contents

- 1 Ukrainian-Controlled Crimea: Is it Safe?

- 2 Taking a Bus Down the Arabat Spit?

- 3 Driving Down the Arabat Spit (Арабатська Стрілка) with Yuri

- 4 Heniches’k Hot Springs (Гаряче Джерело)

- 5 Pink Lake (Рожеве Озеро)

- 6 The Syvash (Сиваш) aka ‘Putrid Sea’ aka ‘Rotten Sea’

- 7 The Abandoned Iron Train Bridge of Heniches’k

- 8 Thanks for Reading!

Ukrainian-Controlled Crimea: Is it Safe?

Yes. Since 2014 there has been nothing really going on on the Arabat Spit. One should of course not try to cross into Crimea from Kherson, but chances are that people who are better informed than you will stop you on time. Of course, things can change. Always check the date on this article.

Taking a Bus Down the Arabat Spit?

I really wanted to do a day trip down the Arabat Spit and see something Wikipedia called the Syvash aka ‘the Putrid Sea’. Appealing name? Not at all. But there’s also something about it that makes me want to check and take a sniff? Are we talking blue cheese putrid or rotten egg putrid? I need to know.

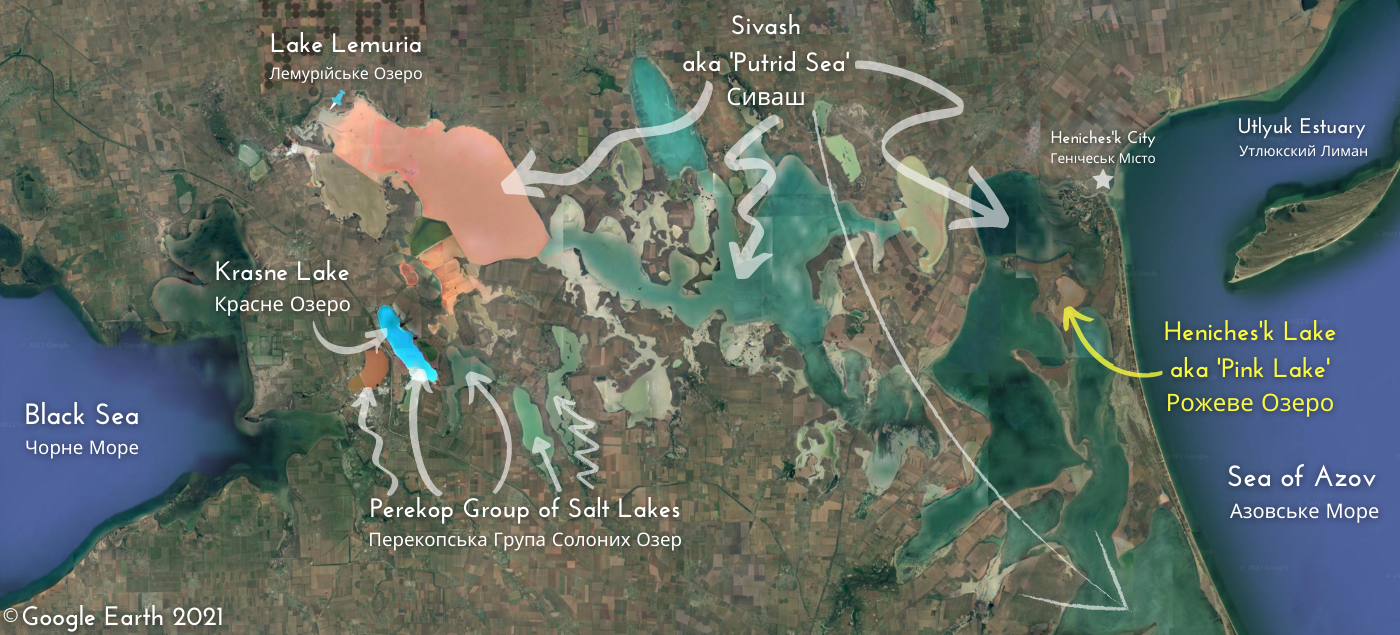

I analyzed two maps and found out that there are hot springs on the southern end (originally called “Hot Spring” in Ukrainian: Гаряче Джерело) and a pink lake (originally called “Pink Lake” in Ukrainian: Рожеве Озеро) west of the spit and kind of embedded in it. First, I thought the only pink lake in the area was the Wikipedia-famous Lake Lemuria (Лемурійське Озеро), but if you go on satellite view, there are tons of them that might or might not be pink during a visit since it depends on a bunch of factors that might not be present year-round.

Jonas was very down with going there, but how? There must be a marshrutka going there, even if it makes a million stops. OSM confirmed that there were a lot of bus stops on the road of the Arabat Spit. But where do these buses originate? And are they still running outside of the main tourist season? Next to the ATB in Heniches’k there’s also a taxi stand. So perhaps it would be okay to take a non-Uber taxi one way and then hitchhike back. But then it would be likely we’d only visit the hot springs and not also the Pink Lake; it’s a little out of the way. And will the pink lake even be pink in rainy and stormy October?

We decided to ask these questions to our Booking.com host Yuri, who speaks good English and so far has been really helpful with stuff around Heniches’k. He said that the Pink Lake is probably still pink and that we should absolutely go to the hot springs. If we want he can drive us there tomorrow. Jonas and I discussed it and went over the map once more. We decided to take Yuri up on his offer.

Great, we don’t have to do all of the thinking with imperfect information!

Note: I think it’s very possible to do this trip with a combination of taking the bus, hitchhiking, and walking. The most difficult part is visiting the Pink Lake, which takes either a long walk (past barking dogs) or hitchhiking.

Driving Down the Arabat Spit (Арабатська Стрілка) with Yuri

The morning of, we have packed two day bags full of towels, water shoes, snacks, water, waterproof bags and phone cases, shoehorn, and anything random that sounded possibly useful. I already put on my bikini to avoid dressing and undressing too often. Yuri knocked on the door exactly at 10:00. We went to his car and dropped our stuff in the trunk of this reasonably-sized car that’s definitely not meant for off-roading but can probably surprise you. I sat in the passenger seat and Jonas in the back. Off we go, driving south to the Haryache Dzherelo. Once we cross the Heniches’k/Thin Strait (Ukrainian: Тонка протока), we’re officially on the Arabat Spit and in Crimea.

We pass the abandoned construction site of a waterpark. Yuri mentions that they started building it, but never finished it. The money ran out or the project became unviable or something like that. What’s left is a fenced-off site with metal lattice towers that would have held together slides for an endless parade of screaming children. It’s much better this way. “They built another waterpark further down the road. That one works in summer.”

The bus shelters along the route are very cute and frequent. This place definitely sees a lot of domestic tourists during the summer. But did I see a bus? I’m not sure. People do live along this stretch, so it makes sense to maintain the route outside of the season. And remarkably, this stretch of road is one of the nicer ones I’ve seen in Ukraine, which leads us to arrive at the hot springs quite quickly.

Yuri asks if we want to rent something of a private booth at the hot springs. In that case, you have a little indoor dressing area for your group and a key to lock it all. It’s not a bad idea, but it’s probably a lot more expensive? Yuri says it’s usually a lot more expensive, but that if it’s out of season and not so busy, it’s usually only a bit more than the standard fee of ₴ 50 per person.

Yuri pulls into an area that says market in the town of Shchaslyvtseve (Щасливцеве) and parks the car there. He asks us if we want to take off our shoes and leave them in the car or take them to the hot springs. I don’t know the fine details of shoe management at hot springs. I’ve seen online that there’s also a sanatorium attached to the hot springs site. But it’s really cold and windy and I’d like to keep my shoes on for as long as possible. Do I even want to undress in this weather and sit in a hot puddle of water? What am I doing here?

We walk through a gate with an unmanned ticket booth to some beachy place. You can see the sign for the hot springs in the distance and there’s a trail of humans going in both directions in flip-flops and other bathing gear. The people coming back from the hot springs look happy and healthy and one guy even walks barefoot and in just his speedos back to his car.

I’m snapping some pictures and filming a bit for a potential vlog while Jonas and Yuri buy tickets. I receive one of those paper festival bracelets from a guy to enter the site. We try to get a locker, but the screen is turned off. Another guy who works there walks up to us and says “Не работает.” We figured that much.

Yuri points towards the various ponds of steaming and non-steaming water. “That one is warm, that one is hot, and those are all cold”. There are quite some of the typical labyrinth-style changing booths strategically placed around the site and we pick one to change.

Heniches’k Hot Springs (Гаряче Джерело)

We drop our dry clothes on a bench, walk past a sign that tells people not to stay in the hot water longer than 10 minutes and walk in our flip-flops over the sandy ground to the warm puddle. It’s windy and so cold and I am not enjoying this. My flip-flops are too lightweight to stay in one place, so I put Jonas’ flip-flops on top. We get down the stairs into the hot water with our feet. Tingly. My feet are so cold that they react with the hot water and turn red. With every step down the tingly and itchy sensation goes up until it stops. I hop in and it’s… nice.

We’re among a lot of people who are happy to be there, taking selfies and videos about their late-season holiday experience in southern Ukraine. I decide to go forward with making the vlog until we warm up enough to realize this bath isn’t very hot. So we grab our flip-flops and walk over to the hot bath, which has a sort of fountain in the middle that spits out really hot water. Entering this bath was a little more difficult because it was actually hot. We spotted Yuri sitting close to the source fountain. That’s where many men vie for the opportunity to have the scalding-hot water-jet directly on their shoulders. We try to pass by the source as close as comfortable but can’t do better than 1.5 meters.

Swimming around the source of the heat we met up with Yuri and talked a bit about the experience. People do come here to improve their health. Some people come here in an attempt to cure or alleviate those standard ailments of the skin, musculoskeletal system, and of course cancer. As always, it’s more belief and wishful thinking than science. Most people seem to be here just to have a nice hot bath.

One of the markers on Google Maps refers to this place as the ‘Radon thermal source’ (Радонове термальне джерело) but none of the reviews mention radon, radium, or radioactivity and I haven’t come across any information about it on-site. I’ve heard about radon baths and spa treatments before in the context of Austria, Czechia, and Germany, but never Ukraine. Considering the whole Chornobyl history, my guess is that ‘radioactive therapy’ is not exactly a good selling point. But I have to ask Yuri about it, who neither confirms nor denies that this hot spring has radon in it. After our Chornobyl tour, I’m not too concerned with little a radioactivity as a treat in a place like this.

Next to the big pond, there’s another big one that’s cold. Jonas and I have observed many people dipping in there to cool off. I’m feeling a little woozy in the head and the cold bath is always my favorite thing at any spa, banya, sauna, or onsen experience. We make our way over there and Jonas goes in first, breathing heavily from the temperature shock. It’s not complete without a full immersion, so once we’re deep enough to plop down, we do that. Then we head back to the warm one before going back into the hot one. I ask Yuri if he has gone into the cold pond, considering the whole 10-minute suggestion, but he shrugged and laughed it off.

We’re really getting into it now. With so many people around it’s a very different experience from our banya day at Lake Issyk-Kul in Kyrgyzstan earlier this year. We visit the cold one another time and directly go into the hot pond, like a pro. Before we decide to leave, Jonas and I go into the cold pond one more time so we feel nice and warm in the cold wind while drying off and getting changed. But the changing booths are occupied for a very long time and as healthy as I felt immediately out of the bath, I slowly return to being cold and miserable.

These hot springs we visited in the Heniches’k area aren’t the only ones that claim to have special properties. There’s also Vodolikarnya “Haryache Dzherelo”, a glycerin (?!) lake, a radon lake with bunnies and mosquitoes, and a very salty lake where you can float. I couldn’t confirm all of these exist.

As for the hot water springs, the story goes that during oil and gas prospecting in the 1970s, the geologists drilled holes and hit underground lakes of more than a kilometer depth. These waters contained loads of minerals and other goodies. Once the geologists left the site, the locals started taking baths in these warm puddles until some local entrepreneurs started building spas to capitalize on that stuff, of course making wild claims about their healing properties.

Pink Lake (Рожеве Озеро)

We walk back to the car and pass over the market, where I spot a tandyr and guys selling samsa and chebureki. A mix between Crimean Tatar and Uzbek cuisine? I had yet to learn about the genocide, deportation (to Uzbekistan) and repatriation of Crimean Tatars under Stalin. I ask if Jonas wants to buy a meaty samsa, but he declines.

Honestly, I would have liked to drive all the way down to Strilkove (Стрілкове) near the border with (Autonomous) Republic of Crimea, but without a reason to go there, I felt it was a reaching request. We drive back to the road where it splits off to the Pink Lake. The road becomes a bit more adventurous and we meet some free-range pigs. We can look over the Syvash to the north where we can see the kites of surfers in the distance. Then we drive through the village of Pryozerne (Приозерне).

The real name of the pink lake is actually Heniches’k Lake, but the internet prefers the more descriptive name. We drive past an old building that functioned as a salt factory in the olden days supposedly until perestroika hit and the business went down and took the village of Pryozerne with it. Yuri comments on its decrepit state and how the concrete is hanging by skinny rebar strings swinging in the incessant winds. “It’s dangerous like this. They should tear it down.”

Yuri parks the car uphill from the lake and with the dense blanket of clouds it’s difficult to see. It’s kind of pink, I guess. We decide to walk down. With the October sun tracing across the sky at a southerly angle, it’s facing that direction that I can see the pinkest hues. In the other direction, it’s just a reflection of the grey sky. Once we walk onto the little wooden piers that are totally not sketchy, we can experience the pinkest stage of Heniches’k Lake. It helps when the fleece of clouds thins out a little and lets more sunshine through.

As is mandatory, we take a bunch of photos at this spot. I pick up a bit of salt from the dry edges. There are some lonesome tables with signs saying they sell salt and a phone number. If it were practical for me to buy souvenirs, I’d definitely buy a bag of salt from one of these mystery vendors. Apparently, it’s also allowed to bring a jar and put some pink goop in it for home use. Needless to say, I’m not trained in finding quality sludge and I’d be worried to accidentally fall in and get, I don’t know, mummified by salt?

But now Yuri wants to drive us to his favorite part of the Syvash.

Here’s a reference satellite map for the entire region. You can see that there’s more than one pink lake in Crimea. Parts of what looks like an individual lake in the west is much pinker than the one we went to. But that’s just part of the Syvash, not an individual lake.

The cause of this color is algae that produce pigments called carotenoids that exist along the yellow-orange-red spectrum. This algae’s name is Dunaliella Salina and this organism loves salty environments. There’s also a single-celled organism called Halobacterium Salinarum that can produce the same pigment, but I’m not sure if this one also lives in Heniches’k Lake.

With high salinity, heat, and sunshine, a lake can go from meh to bright pink. Why do they do this? The algae do it to protect their chlorophyll from burning, so I think of it like suncream for algae. No, I’m not a marine biologist.

Satellite image from Google Earth. It’s a collage of multiple images taken at different times. Tap and hold the image on your phone or hover over the image with your mouse to see labels. You can see how big the Syvash is considering the only two narrow inlets of water are at Heniches’k. Highlighted in yellow is the pink lake of Heniches’k.

Tips for Visiting Heniches’k Pink Lake: How to Make Sure it’s Pink?

After lots of digging, I found this live webcam at the village of Pryozerne. This is what it looked like mid-November before noon:

They also state that the lake reaches its maximum pink color in August and September. That’s also the time when it’s busiest with tourists visiting the lake to harvest the pink salt and brine. Another name for the pink salt is “kefai salt” (кефайская соль), which roughly translates to ‘living salt’. These sources claim that it can be found only in four places on earth. The lake is the least pink in spring.

The Syvash (Сиваш) aka ‘Putrid Sea’ aka ‘Rotten Sea’

We drive away from the pink lake to the side of the Syvash that Yuri loves the most. The road has become sandy, but we drive through it anyway. Once across a high point, a very bright blue lake appears. Even though this corner is part of the humongous Syvash lake system, it looks different from the other side of the peninsula that houses the pink lake. On the top of the dunes, we can see a bit of both lakes, blue and pink, like one of those grotesque gender reveal parties.

We all walk down to the shore and I give the water a little touch. Not too cold. Apparently, you can just go camping here, no problem, not even in summer. But I like the comfort of our very big home in Heniches’k with the pool table and the quiet. It is truly windy here and I’m getting cold to the bone once again.

Yuri suggests we drive around the Pink Lake via the dirt road that surrounds it on this strange peninsula. I’d be very down. He tries to drive it for a little while and I do my best to guide with GPS. But we end up on the wrong trail with very large bushes that the car can’t really pass over with ease. So we turn around and drive back to the abandoned salt factory at the Pink Lake followed by the main road.

The Abandoned Iron Train Bridge of Heniches’k

We had wanted to visit the Iron Bridge of Heniches’k (Железный Мост Геническ) on an earlier day hike, but we ended up being too tired to detour here. On the map, it could have been a dedicated pedestrian bridge. But now that we were in the comfort of the car, Yuri told us that it’s a train bridge from the time the Heniches’k train still ran down the Arabat Spit to the salt (and other) factories.

Apparently, it’s a bridge by Austrian design from the First World War. Yes, it’s over 100 years old and still standing—albeit a bit rusty. The company (Waagner-Biro) still exists and is building bridges that I’ve hitchhiked over in Belize and we’ve crossed by train or paddled nearby on the Austrian Danube. Oddly enough, their website does not take credit for or pride in building this centenarian bridge that has outlived its design life by… a lot.

Yuri said that after it had been built in Austria, it was disassembled and then moved to Belarus. It first served as a train bridge nearby Orsha to cross the (relatively young) Dnieper River, before they packed it up again like a piece of IKEA furniture and moved it to its current and final location in southern Ukraine in 1951. The railroad connected the terminal town of Strilkove to Heniches’k and the junction at Novooleksiivka and although it was mostly to transport salt, there was also a passenger service. In 1971, a storm destroyed part of this line and the authorities removed the railroad tracks to the Arabat Spit but left the bridge in place.

Since it’s so rusty, I’m confident to say that this steel truss bridge will not make another appearance in a new country again.

(Sources: 3D Kherson, Na More, Genichesk, and this strange site)

Anyway, back to our regular programming.

I asked Yuri if it’s possible to drive over the bridge with a car. He said “Yes, it’s possible, but it’s very dangerous.”

I expected that Yuri wanted to park the car and walk a little onto the bridge and then return to drive back the way we came. But instead, he put the narrow car into gear and just… drove onto it. Is this what tempting fate looks like?

There were some funny sounds coming from the wheels touching the weird railroad tracks that had been asphalted over about 15 years ago. But it worked. The biggest danger came from accidentally pissing off one of the many fishermen on the bridge.

Thanks for Reading!

Really enjoyed your descriptive and knowledgeable narrative of the Arabat Spit, a place I never heard of until today. The rusty bridge was my favorite. Hope to check out some of your other journeys.

Thank you Linda